12 Mini Military Aircraft You Might Not Have Known Existed

Commercial vehicles come in a wide variety of shapes and sizes that cater to different needs and budgets. Smaller cars are more fuel efficient and less expensive, whereas larger trucks can haul more cargo and take more punishment. Kind of obvious when you think about it, and the same logic can apply to military vehicles, including aircraft.

When you think about small vehicles utilized in a combat setting, you probably jump to speedy military drones like the MQ-1B Predator. Except they aren't as small as you might imagine. Yes, MQ-1Bs are only 27 feet long, which is around half the length of an F-35 Lightning II fighter jet, but military engineers have experimented with aircraft designs that are even smaller than the Predator drone. Most, if not all, of these ideas never made it to the battlefield, but they still were legitimate attempts to cram jet, plane, and helicopter technology into tiny packages.

Unlike the Predator drone, most of these attempts have fallen through the cracks of history for one reason or another. Perhaps military engineers worked on these ideas long ago. Perhaps the designs were so unusual that our memories had difficulty holding a firm grasp on them. Regardless of the hows and whys, they all had two things in common: They were small, and they were aircraft. Read on to learn more about some obscure attempts to make miniaturized military hardware.

Lockheed XFV-1

Unlike standard fighter jets, Vertical Takeoff and Landing (VTOL) jets can take off and land with a minimal amount of runway. VTOL technology has come a long way since it was first invented. In fact, engineers have been experimenting with VTOL tech since before jets were widely adopted.

After World War II, the U.S. Navy brainstormed how to shore up ship defenses. The organization hit upon the idea of creating aircraft that could take off vertically. The result was the Lockheed XFV-1 – the Lockheed Corporation wouldn't merge with the Martin Corporation until 1995. This experimental plane was powered by two three-bladed Curtiss-Wright propellers that rotated counter to one another. You're probably wondering how the Lockheed XFV-1 would have achieved vertical takeoff, and the answer is similar to the method used by a Sky Dancers toy. The plane was designed to sit on its rear tail fins and shoot up vertically with over 10,000 pounds of thrust. At least, that was the plan.

The Lockheed XFV-1 was 37 feet long with 30-foot wings. While this plane was technically larger than propeller-powered fighter aircraft that flew during World War II, many other planes of the time, especially those powered by jet engines, dwarfed the XFV-1. While the Lockheed XFV-1 made several conventional flights (i.e., horizontal launches), it never launched from a vertical position. Pilots cited issues such as difficulty determining sink, climb, and rotation. As a result, the Lockheed XFV project never truly made it off the ground.

De Havilland Vampire

Vehicle designs change with the times, and early renditions rarely look like modern iterations. Tanks, for instance, started with rhomboidal treads and cannons sticking out of the sides — a far cry from current designs. Fighter jets underwent a similar evolution.

De Havilland's DH100 Vampire was a series of firsts for jet fighters. While it wasn't the first combat jet fighter ever — that honor goes to the Messerschmitt Me 262 – it was equipped with the first jet engines built in Australia and was the first jet aircraft to successfully take off from and land on an aircraft carrier.

Since the de Havilland DH100 Vampire was an early-generation jet fighter, designers had a very different idea of how these planes should look. As a result, the DH100 Vampire sported an elongated, egg-shaped fuselage and two tails that connected near the rear via a fin. Moreover, at barely 31 feet long with a wingspan of almost 38 feet, the de Havilland DH100 Vampire is on the smaller side. Part of the fighter's small size can be traced to its unorthodox design.

Folland Gnat/HAL Ajeet

Fighter jets are indispensable, but they're also expensive to research, build, and maintain. If designers can cut corners to save a few thousand bucks, they will. Turns out some features, such as length, aren't as important as we thought.

The Folland Gnat was a fighter jet invented for one reason: the production of a lightweight jet with low operational costs. That technically turned out to be true, but while these aircraft were relatively inexpensive to operate, Folland Gnats weren't easy to maintain. Eventually, the British Royal Air Force transitioned its fleets of Gnats from fighters to trainers, but the planes did find a second wind serving Indian forces as the HAL Ajeet.

To be fair, the Folland Gnat was an effective fighter jet, and it entered our list as the smallest fighter jet to have ever entered service. At 31 feet long with a 10-foot height, the Gnat lived up to its namesake as a truly minuscule fighter plane. The Folland Gnat could even hit Mach One, albeit during shallow dives. Of course, this small size came at the cost of armaments. Gnats were outfitted with two 30-millimeter cannons, and while they could carry bombs and rockets. Unlike many aircraft in this article, at least the Folland Gnat saw some action.

Heinkel He 162

You could have all the money in the world to fund a plane's development and construction, but cash is nothing without proper materials. Sometimes, engineers think up ways to construct vehicles out of unconventional mediums due to desperation, and other times, they are part of an evil, fascistic regime that cares nothing for its soldiers. Sometimes both.

As World War II dragged on, Nazi forces found themselves in an increasingly unwinnable scenario, so engineers devised some crazy and dangerous ways to turn things around. One such idea was the Heinkel He 162. The plane was hastily designed to be an emergency, lightweight fighter that could be built and flown as quickly as possible with as few strategic materials (i.e., steel and aluminum) as possible. Nazi engineers settled on plywood and even tried to make the planes so easy to pilot that teenagers could do it. Because Nazi higher-ups actually wanted teenagers to throw their lives away if it meant delaying inevitable defeat.

The unconventional building materials contributed to the Heinkel He 162's low weight as much as the size of the soapbox derby jet fighter. At just over 29 feet long with a wingspan of over 23 feet, the Heinkel He 162 lived up to its nickname of Spatz (German for "Sparrow"). Thankfully, the plane proved too dangerous to fly and even more dangerous to launch and land for experienced pilots, let alone Hitler Youth draftees. Had the Heinkel He 162 plan come to fruition, none of the pilots would have enjoyed good odds of survival.

Ryan X-13 Vertijet

As it turns out, the Lockheed XFV-1 was only one of several early attempts to create VTOL planes. Another company, Ryan Aeronautical, took a stab at the design, only this time engineers were able to work in actual jet engines.

The Ryan X-13 Vertijet was a proof-of-concept jet that, as its name spells out, was designed to shoot up like a rocket during takeoff, transfer to horizontal flight, and finally land back in a vertical position. Unlike the Lockheed XFV-1, the Ryan X-13 was able to demonstrate the advantages of its design concept and launch successfully. However, despite this seeming success, the project was eventually canceled due to a lack of funding and potential.

While the Ryan X-13's design was functionally sound, the plane wasn't exactly a looker. The prototype jet was approximately 23 feet long with a 21-foot wingspan. The engine and fuselage created a single, cigar-shaped body, while the wings spread out like an arrowhead, creating what is known as a delta wing configuration. Even though the Ryan X-13's physical design proved to be a dead end, it still paved the way for true VTOL fighter planes such as the Harrier jump jet.

Rockwell HiMAT

NASA is an integral part of life in the United States and around the globe. We use countless devices invented by NASA, from LEDs to wireless headsets. And while NASA isn't a branch of the U.S. military, the organization has produced some test vehicles intended for its use.

The Rockwell Highly Maneuverable Aircraft Technology (HiMAT) was a collaboration between NASA, the Air Force Flight Dynamics Laboratory Vehicle Dynamics Division, and Rockwell. While not technically a drone, it wasn't quite a plane, either. The aircraft was remotely piloted to test different features for future fighter planes, including the Flight Test Maneuver Autopilot (FTMAP) system.

Unlike other test planes, the HiMAT was not full scale. Instead, it was built in 4/10 scale, although sources such as NASA place it closer to a 0.44 scale, which might explain why the HiMAT was so small. The final model for the jet stretched a little over 22 feet in length and sported a wingspan of approximately 15 feet. Unfortunately, this small size was more restrictive than initially anticipated. Plus, the aircraft was difficult to maintain. However, the test flights were regarded as a success thanks to the model's durability. You can find one Rockwell HiMAT on display at the National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C., and another in the Armstrong Flight Research Center in Kern County, California.

Vought V-173 Flying Pancake

The early days of aviation were widely considered the Wild West of plane design. Back then, engineers and would-be pilots threw every design imaginable at the wall to see what stuck ... er, flew. But even after people learned that two wings and a propeller make planes fly, engineers have occasionally tried unorthodox designs.

The Vought V-173, also known as the Flying Pancake, was designed by the aeronautical engineer Charles Zimmerman, who made a name for himself developing eccentric aircraft concepts. Moreover, Zimmerman didn't nickname the Vought V-173 the Flying Pancake because he was hungry when he drew up the plans. The vehicle sported a unique circular wing design with four small fins — two horizontal and two vertical — in the back and two large propellers in the front. Zimmerman's logic was that the design maintained a uniform flow over the entire plane, thus reducing drag.

Since the Vought V-173 indeed looked like a flying pancake — or an A-Wing Interceptor if you squint your eyes — its dimensions didn't quite measure up to other military aircraft. The plane's single wing was 23.3 feet in diameter (the closest we'll ever get to its wingspan) with a length that measured over 26 feet. Despite the vehicle's design, the Vought V-173 was actually easy to handle and withstood several forced landings. Had it not been for the advent of the turbojet engine, Zimmerman's design could have become a staple of U.S. Navy aircraft carriers.

AvroCar

Mankind has wanted hover technology ever since we developed the concept of hovering. Of course, part of that desire stems from our inability to develop a bona fide working hover technology system. The U.S. government gave it a stab, and it didn't work.

The AvroCar is one big misnomer because it looks nothing like a car and instead resembles an old-school flying saucer. The vehicle was designed by the organization A.V. Roe Aircraft Limited (Avro Aircraft Limited) and featured a central turbo rotor that lifted the vehicle off the ground via a cushion of air. Avro Aircraft Limited originally developed the AvroCar for the Canadian government, but when the project proved too expensive, the U.S. Army and Air Force picked up the tab. The military branches sought an all-terrain troop transport and reconnaissance vehicle, as well as a VTOL aircraft capable of flying under radar and then accelerating to supersonic speeds. Both thought the AvroCar could fulfill these requirements, and both were wrong.

With a wingspan (technically wing diameter due to its circular shape) of 18 feet, the AvroCar was rather small. While it was a miracle that the designers were able to make such a semi-miniature aircraft hover, they couldn't make it hover reliably. Hovering over 3 feet above the ground caused the vehicle to pitch and roll uncontrollably, and it couldn't levitate faster than 35 mph — well below the desired supersonic speed. Instead of revolutionizing military transport, the AvroCar became a historical curiosity.

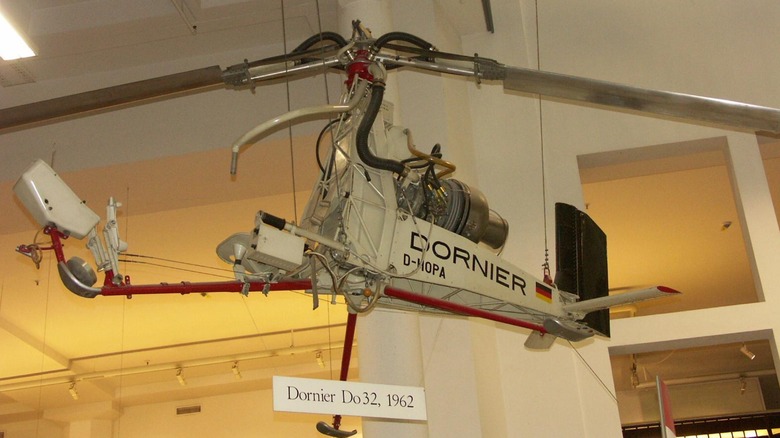

Dornier Do 32

How do you store planes? Some are small enough to sit in an average garage, while others have wings that move to fit into tight spaces. But how do you store helicopters? German engineers had a unique idea.

The Dornier Do 32 was among the earliest helicopters built by the German helicopter industry after World War II. The vehicle was little more than a frame and motor, with the pilot exposed to the elements. Dornier Flugzeugwerke's first Do 32s were single-occupant helicopters, and while the company had high hopes for its two-seat variant, which Dornier showed off at a Paris Air Show, the helicopter ultimately failed financially.

As you can probably guess, the Dornier Do 32 was classified as an ultra-lightweight helicopter. At under 13 feet long and less than 3 feet wide (not counting the rotor, which was over 24 feet in diameter), the Do 32 was so small that users could fold the helicopter away in a container they could tow with a truck. The container even doubled as a takeoff and landing pad, which made transportation even easier. However, since the Dornier Do 32 was so small, it only had enough fuel for 50 minutes of sustained flight. There's always a catch.

Curtiss-Wright VZ-7

Toy drones come in a lot of shapes and sizes, but many rely on four propellers. This design sets them apart from helicopters and other rotorcraft and makes one wonder how engineers came up with the idea. Perhaps they were inspired by a failed U.S. military VTOL design.

If you looked at a Curtiss-Wright VZ-7 without any context, you might never know what it was. This aircraft was originally designed for the United States Army Transportation Corps as a "light VTOL utility vehicle." Designers attached four propellers around a rectangular central platform, and while the design looked fairly unstable, it was actually easy to control and passed initial test flights.

When Curtiss-Wright built the first batch of VZ-7s, the vehicles came in at just under 17 feet long with a width of barely 16 feet. Moreover, each test aircraft could fit at most two crewmembers. You might wonder why the surprisingly solid quadcopter never made it past the testing phase. Turns out a passing grade isn't good enough for the U.S. military. The Curtiss-Wright VZ-7 couldn't fly high or fast enough to impress the Army's higher-ups, so the project was subsequently shelved.

Hiller YH-32/XHOE-1 Hornet

A helicopter's rotors provide all of the vehicle's lift and propulsion. This central component lets helicopters hover, change direction in the air, and so much more. However, rotors also limit a helicopter's performance because you can only get so much out of spinning and tilting them. Some engineers thought they could increase a helicopter rotor's output by strapping jet engines to the blades.

The Hiller YH-32 Hornet, alternatively known as the Hiller HOE-1 or XHOE-1, was a tiny two-seater helicopter that set itself apart from similar rotorcrafts thanks to the ramjets built into each rotor. Unlike other jet engines, ramjets have no moving parts. Instead of relying on turbines, ramjets generate thrust via air pressure passing through the intake. And combusting fuel as it mixes with the air, of course.

At only 13 feet long with a rotor diameter of 23 feet, the Hiller Hornets were downright tiny. Hiller originally constructed these helicopters for civilians, but the U.S. Army and Navy purchased some to test applications for their technology. For instance, the Army tried to see if the helicopters could make good artillery spotters, but the ramjets made too much noise and were easily spotted. To make matters worse, ramjets are at their most efficient at supersonic speeds, and since Hiller's YH-32 Hornet rotors couldn't spin that fast, they weren't worth the fuel.

McDonnell XF-85 Goblin

Bomber planes can unleash a swath of destruction on the battlefield, but as their name suggests, they mostly carry bombs. Plus, they're not very fast and rely on accompanying planes to handle enemy fighters. But therein lies another problem: Most bombers can fly much further than any fighter plane. Instead of trying to extend the range of planes meant to defend bombers, aeronautical designers had a different solution.

At the beginning of the Cold War, U.S. military engineers asked a question: What if a bomber could carry its own intercept planes? This idea spawned the McDonnell XF-85 Goblin, a squat fighter jet classified as a parasite fighter. The plan was that a Convair B-36 Peacemaker bomber would carry an XF-85 Goblin in its bomb bay, launch it via a mechanism to fend off incoming attackers, then store it back in the bomb bay when its mission was complete.

At first glance, an XF-85 Goblin looks like what would happen if someone tried to turn a jet fighter from an old Looney Tunes cartoon into a real object. At a little over 14 feet long and with a 21-foot wingspan, the Goblin is one of the smallest fighter jets ever designed. More importantly, the plane was able to fly and launch from modified B-29s, but recovery proved impossible thanks to turbulence. The project was abandoned after aeronautical engineers invented mid-flight refueling, which rendered the Goblin obsolete.