Operation Paperclip: 10 Inventions & Scientific Advances The Controversial Program Produced

Every species on the planet has a few evolutionary advantages that are key to survival. For us humans, it's the ability to use tools. Granted, we're not the only species that knows how to use them, but we're the only one that produces them on a global scale, sometimes even tapping talent from the other side of the world.

Because modern society was built around — and by — countless tools, we often put those who imagine them on a pedestal. For instance, Leonardo da Vinci was a polymath (an expert in many fields) who dreamt up countless inventions, many of which weren't realized until centuries after his death. However, history is rarely as we imagine. Many inventors had more than a few skeletons in their closets, but some downright filled their closets with skeletons to the bursting point and kept stuffing more in. One would think they would be punished for these crimes, but instead they were recruited to help the United States government fight what it considered a more prominent threat.

Read on to learn about some of history's biggest monsters and how they helped guide the course of the United States (and possibly the rest of the world) through their inventions. Please note this is not an attempt to make it sound like they were misunderstood, just a history lesson about one of the most uncomfortable parts of U.S. history.

What Was Operation Paperclip?

After World War II, the Axis powers of Japan, Italy, and Germany lay battered, broken, and, most importantly, defeated. While their forces were no longer able to fight, the minds that powered the war machines of these regimes were still alive, albeit not for long if the Nuremberg Trials (and similar tribunals) had anything to say about it. Then the United States intervened.

In 1945, the United States Government enacted a top-secret mission dubbed Operation Paperclip. The goal was as simple: Recruit as many Nazi scientists as possible. Why would the United States harbor rocket scientists and aerospace engineers party to one of the most horrendous acts of violence and unbridled cruelty in human history? Because the government was stuck in its "Better dead than Red" phase. The fallout of overlooking the crimes of people who had a role in the Holocaust was considered a small price to pay if it meant getting a leg up on the Russkis.

Like many acts of espionage, Operation Paperclip was divided into multiple phases. United States forces gathered information on Nazi Germany's top scientists, delivered these findings to their superiors, and retrieved the people deemed important to the future of the United States. The operation's name, "Paperclip," came from how U.S. officers marked the Nazis they wanted to recruit: Paperclips were attached to their dossiers.

[Featured image by Wikimedia Commons Public Domain | Cropped and scaled]

Saturn V Rocket

During World War II, Germany's V-2 rocket was considered a gamechanger. The weapon was the world's first long-range guided ballistic missile. Allied forces grew to fear the V-2 rocket. Who better to shoot the United States into the upcoming space race than the team behind this devastating weapon?

The Saturn V rocket, which was used to launch Apollo 11, was the brainchild of Wernher von Braun, the designer of the V-2 rocket. While von Braun invented the V-2, the rocket's assembly plant was manned mostly by slave labor, and von Braun was aware of this practice, as well as the high mortality rate of these unwilling workers. However, unlike many of his contemporaries, von Braun saw the writing on the wall in late 1944 and was ready to surrender to United States soldiers so he could continue his work. Without slave labor, of course.

Under Operation Paperclip, von Braun worked alongside other key members of his V-2 rocket team to develop guided rockets. While the Saturn V rocket was the most famous of these post-war creations, they also developed the rocket that shot the United States' first satellite, Explorer 1, into orbit: The Jupiter C rocket. Moreover, von Braun and his cohorts were among the biggest advocates for space exploration during the late 1950s and the 1960s. They even authored several books and magazine articles on the subject.

Space Medicine

Humans are the only species that lives on every continent and biome on the planet. However, if we were to ever travel up into space, we had to figure out how to survive in the cold vacuum beyond Earth. And, well, we did.

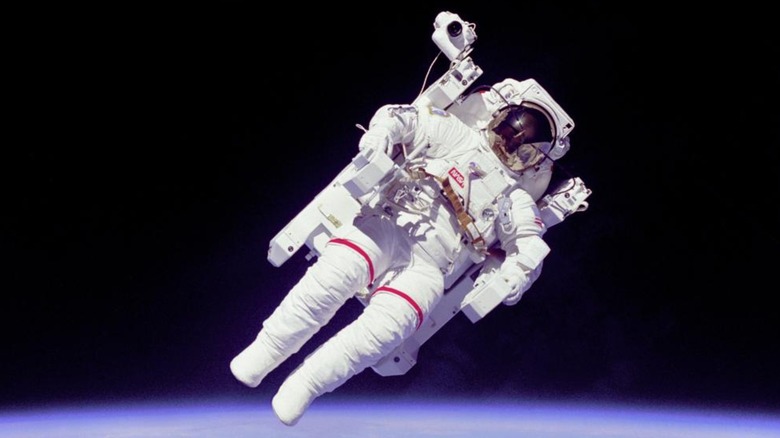

Hubertus Strughold is widely regarded as the "Father of Space Medicine," and it's not hard to see why. He designed the life support systems and pressure suits used by Gemini and Apollo mission astronauts, and he even trained the flight surgeons and medical staff of the Apollo program. Without Strughold, Apollo 11 astronauts wouldn't have made it to the moon and back safe and sound. While this sounds like the work of a hero, Strughold was anything but.

Out of all the Nazis selected for Operation Paperclip, Strughold was one of the most controversial, although nobody knew the true depth of his depravity until after his death. Strughold led inhumane experiments on prisoners in two of the Nazi regime's most infamous concentration camps: Auschwitz and Dachau. Under his watch, countless prisoners were frozen and placed into low-pressure chambers to simulate the effects of high-altitude freefall on the human body. Many of these unwilling test subjects didn't survive. Strughold's history sours the entire U.S. space program. Yes, Neil Armstrong's step on the moon was a momentous occasion, and he is a cultural icon, but that doesn't erase the stain Strughold left during World War II.

Ablative Heat Shields

Rocketing up into outer space is one thing, but getting down is a completely different challenge entirely since the Earth's atmosphere has a tendency to burn up anything that enters it. If you can't stand the heat, there's no way back.

Ablative heat shields are a crucial element of spacecraft design, as they protect vessels during reentry. These "shields" (which are actually tiles, not shields as depicted in "Star Trek") are constructed out of several materials and are designed to take the brunt of the atmosphere's punishment and burn up in the shuttle's stead. As such, engineers must attach a fresh coat of heat shields after every trip. Even the smallest error can result in catastrophe; the Columbia disaster was the result of foam debris dislodging a few of these ablative shields.

The majority of Nazi engineers rounded up through Operation Paperclip were rocket scientists, one of whom was Eberhard Rees. While he worked on the V-2 rocket alongside other Nazi engineers, he is probably best known as the mind behind ablative heat shields. Among his other post-war accomplishments, Eberhard became the Deputy Director of Development Operations for the United States' Army Ballistic Missile Agency, as well as the director of the Marshall Space Flight Center, where he led the lunar roving vehicle program.

NASA

The sad fact of reality is that while the United States began Operation Paperclip to help staff its space program, the U.S. didn't really have one before they started recruiting Nazis. These scientists created the tech necessary to reach space, but they were so good at it that they were quickly promoted.

Since we wouldn't have gotten to the moon if it weren't for Wernher von Braun, he was eventually elevated to Director at the Marshall Space Flight Center. Kurt Debus was another notable Nazi figure in NASA's early days, as he served as the Director at NASA's then-recent John F. Kennedy Space Center from 1962 to 1974. Like the other Operation Paperclip recruits mentioned so far, Debus worked with von Braun on the Apollo rocket, but he later oversaw the construction of the rocket's facilities, as well as JFK Space Center next door.

While many Nazi scientists essentially ran NASA in its early days, not all did so from the position of "Director." Helmut Horn, a physicist and expert in guided missiles, helped investigate the lunar orbit rendezvous system used in the Apollo missions. Before that, Horn was yet another member of von Braun's post-war team. While Horn never made it to the position of director, he was given the title of Deputy Director at the Marshall Space Flight Center's Aero-Astrodynamics Laboratory.

Supersonic Flight

While Nazi scientists developed plenty of inventions in the United States thanks to Operation Paperclip, they rarely started from scratch. Each engineer was conscripted for what they knew and what the United States government big wigs thought this knowledge could create. Operation Paperclip recruits were merely continuing what they did before the war ended.

We can trace much of what the United States knows about supersonic flight technology back to the Nazi aerospace engineer Adolf Busemann. During World War II, he began pioneering a new wing shape: swept wings. For those unversed in aircraft design, swept wings reduce drag across the wings and prevent (or at least delay the production of) shockwaves that could potentially stall an engine. Busemann and his high-flying ideas were ahead of their time since then-contemporary plane engines couldn't provide enough thrust to reach speeds where swept wings were useful. However, technology eventually caught up after Operation Paperclip, and Busemann's swept wings were instrumental in conquering supersonic flight.

What are wings capable of withstanding the rigors of supersonic flight without an engine that can shoot them to supersonic speeds? One of Busemann's first assignments after arriving in the United States was writing a paper "on the theory and design of ramjet engines," which are engines that have no moving parts and are most efficient at supersonic speeds. Alexander Lippisch, another Nazi aeronautical engineer and the creator of the aforementioned Lippisch P.31a delta wing aircraft, also contributed to early post-war research into swept wings and ramjets.

Stealth Technology

While United States officers and spies looked deep into Nazi records to determine who they should select for Operation Paperclip, several choices were easier than others. Sometimes the U.S. had their eyes on German scientists long before any U.S. engineers thought they would work alongside Nazis on a more permanent basis.

Stealth technology is commonly used in many military aircraft, especially fighters and bombers. While it doesn't render these planes invisible to the naked eye like a "Star Trek" cloaking device, it does use radar-absorbent coating to prevent enemies from detecting these aircraft early. By the time a potential target sees a stealth fighter or bomber, it's too late to scramble and mount a proper defense. Currently, the F-22 Raptor is the stealthiest jet on the planet.

In March of 1945, German higher-ups sent one Heinz Schlicke via U-boat (the German name for submarine) to aid their allies in Japan. He was supposed to bring them advanced military technology. Prior to this mission, he had begun work on detection stealth technology, starting with the realization that U-boats left oil traces that could be tracked at night via UV fluorescent lights. Two months later, shortly after Germany surrendered, Schlicke was captured and sent to a POW camp. While he was eventually repatriated, he voluntarily left with United States officers after Operation Paperclip marked his experience with "sound and electrical absorption materials" as crucial. This work formed the basis of modern stealth technology.

Hall Effect

The space program was Operation Paperclip's largest contribution to the United States. However, there's more to spaceships than the rocket engines they use to escape the Earth's gravity. Electrical systems are extremely important, especially those involved in steering.

If you use any form of joystick, especially joysticks on video game controllers, you probably enjoy the benefits of the Hall effect. While standard joysticks use potentiometers that measure charges generated by internal parts contacting one another, Hall effect sticks read the fields generated by electrical conductors and magnets inside the device. The result is more reliable and accurate, and more importantly less vulnerable to stick drift due to the lack of internal parts rubbing together and wearing each other out.

While the Hall effect was discovered by Edwin Hall, hence its name, Walter Haeussermann pioneered a good chunk of what we know about the technology. This electrical engineer was part of Wernher von Braun's entourage of Nazi scientists whose profiles were dogeared by Operation Paperclip. Haeussermann specialized in guidance and control, and much of his research revolved around the use of the Hall effect. He even patented a "velocity measurement system" that utilized a Hall effect device. Without Haeussermann's work, we might not have Hall effect joysticks for any industry.

LEDs

While Operation Paperclip primarily targeted Nazi scientists, the United States officers in charge did not suffer from tunnel vision. Anyone with standout expertise in science who might attract unwanted attention from the Soviet Union was fair game.

Unlike most scientists recruited through Operation Paperclip, Kurt Lehovec wasn't a Nazi. He was a Czech physicist who voluntarily sought out asylum in areas occupied by United States forces after the Soviet Army started marching into Prague in 1945. Thanks to Operation Paperclip, Lehovec was selected as a priority scientist and shipped off to the United States where he entered a protracted battle to gain citizenship. Oh, and work on projects that would alter the course of circuit and light engineering.

Lehovec is best known for his work on microchip p-n junction isolation, solar cell photovoltaic effect (more on that later), and for the purposes of this entry, light-emitting diodes, i.e., LEDs. While the British engineer H.J. Round is credited with discovering the concept of LEDs, Lehovec made some serious headway into their construction and use. Lehovec discovered, among other things, how to produce LEDs of different colors. Prior to his work, they only emitted red light. Lehovec also filed a patent for "light emitting silicon carbide diodes." Today, LEDs are commonplace and are used in a wide variety of devices, including energy-efficient light bulbs. The next time you use one to save money on your electricity bill, thank Kurt Lehovec.

Solar Panels/Photovoltaic Solar Cells

Most Nazi engineers scouted through Operation Paperclip worked on inventions synonymous with their fields of expertise. However, some also had lasting impacts on inventions that they contributed to in a smaller degree.

As we previously went over, Lehovec was instrumental in our modern understanding of solar panels and their photovoltaic cells. He is widely considered the first scientist to break down the photovoltaic effect and explain it in terms most people could understand. However, another scientist picked up through Operation Paperclip (this one an actual Nazi) is credited for influencing the future application of solar panels.

Hans Ziegler was an expert in the field of electronics and communication before he was recruited through Operation Paperclip. He was put to work on the United States space program, specifically its satellite division, and was a vocal proponent of using solar cells and batteries to power these devices. Thanks to his convincing arguments, the U.S. Navy built the Vanguard satellite with both chemical batteries and solar cells. Ziegler predicted that the chemical batteries would fail after a few days, whereas the solar-powered batteries would continue running for years.

The satellite proved him right. While it took several years, eventually NASA adapted solar panels as the de facto power source for satellites. If Ziegler hadn't pushed so hard for them in the first place, the world of satellites might look very different.

General Medicine

Not all Nazi scientists recruited through Operation Paperclip were engineers. Due to their general lack of ethics, plenty specialized in the medical field, albeit to weaponize diseases most doctors fight against. Whether or not any of these Nazis continued to do so in the United States is up for debate.

One Nazi who we can say helped people (mostly) after the fall of the Reich was Paul Anton Cibis. During World War II, he specialized in surgeries to repair orbital and eye damage in soldiers, and after he was recruited via Operation Paperclip, Cibis furthered his studies into the human retina and retinal damage. His most important work included research on retinal damage caused by atomic bomb blasts and the use of silicone oil in retinal detachment surgery. While Cibis's work has actual medical applications, the same can't be said for other Operation Paperclip Nazi "doctors."

Erich Traub was recruited by the United States military to work at their new biological warfare laboratory on Plum Island. Traub was supposedly selected for his knowledge of foot-and-mouth disease, which he gained trying to weaponize for Holocaust architect Heinrich Himmler. Traub later became the world's foremost expert on foot-and-mouth disease after the war. Then there was Kurt Blome, one of the many Nazi "doctors" who went on trial in Nuremberg. While Blome was acquitted, it is generally accepted this was because the United States intervened to recruit him to work on one of the most infamous examples of brainwashing experimentation in history: Project MK-Ultra.