How NASA Space Shuttle Tiles Work To Protect Against Extreme Heat

A NASA Space Shuttle Orbiter re-enters the Earth's atmosphere at about 75 miles above sea level and speeds close to 17,500 mph. When slowing down to its landing speed of about 215 mph, the orbiter's external surface can experience temperatures close to 3,000 degrees Fahrenheit from friction due to air resistance.

To put that in perspective, the Space Shuttle Orbiter's airframe is made out of aluminum, which anneals (or softens) at 350 degrees Fahrenheit (177 degrees Celsius). To protect the metal orbiter craft and insulate the occupants — a maximum of eight crew members have ever flown in a single shuttle, but early design drafts envisaged up to 86 astronauts – from the extreme heat and cold of space, NASA (which was originally called NACA) employed reusable heat shield tiles. Those were part of the space agency's Space Shuttle Orbiter Thermal Protection System (TPS), which was first used in the Space Shuttle Columbia.

The original iteration of the system was so difficult to install that it was largely responsible for the 1.5-year delay of Columbia's maiden orbital flight from its original November 1979 target launch date to the April 1981 actual launch date. A single shuttle tile can cost up to $1,000 to make. Prior to the closure of the Space Shuttle program in 2011, NASA began offering Space Shuttle tiles to schools, universities, and museums in a bid to inspire the next generation of space explorers.

How do Space Shuttle tiles work?

The Space Shuttle wasn't the first manned NASA spacecraft to bring back astronauts from orbit, with numerous Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo missions performing the remarkable feat of manned re-entry. However, all the earlier craft used ballistic re-entry trajectories, offered very little maneuverability, and made parachute-powered water landings, according to NASA. The trajectory could mean much faster re-entry velocities closer to 25,000 mph, as was seen in the case of the Apollo moon missions. These non-reusable spacecraft had ablative heat shields that were bonded directly to the capsule's body and designed to "ablate" — that is, controllably burn, taking the brunt of the heat in order to protect the layers below.

With the Space Shuttle program, NASA wanted a maneuverable and reusable orbiter that had a design life of 100 missions. To do this, it developed the Thermal Protection System with several companies, including Rockwell International, Lockheed Martin, and Albany International, to name a few. The system is built out of over 24,300 reusable shield tiles — the number varying slightly depending on each Space Shuttle Orbiter's design.

The TPS design consists of two types of reusable surface insulation (RSI) ceramic glass tiles of different compositions, heat capacities, and densities. Each tile has a different shape and thickness, depending on its placement on the shuttle. One set of tiles provides better thermal shock resistance, another strength, and the final, a mix of the two. Of course, since these are orbiters, the thermal materials had to withstand (and insulate from) both extreme cold and heat. The external surface temperature in a 90-minute orbit can fluctuate between -200 degrees Fahrenheit and 200 degrees Fahrenheit. The system went through a few upgrades in the 30 years NASA operated the Space Shuttle program.

What are Space Shuttle tiles made out of?

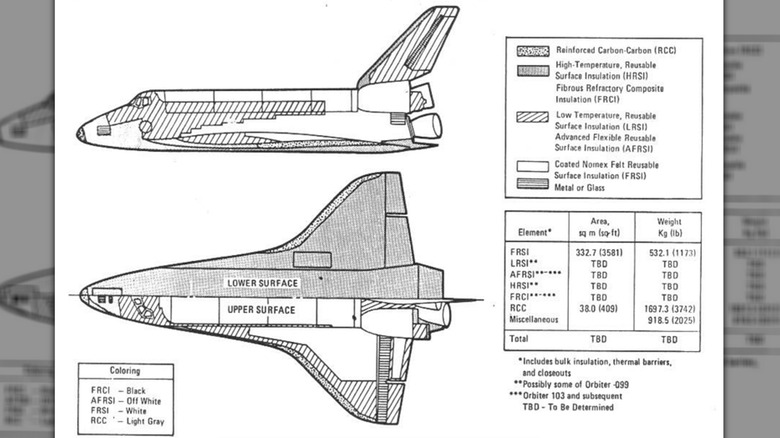

The above schematic shows a typical RSI tile layout on a Space Shuttle Orbiter. The white tiles are low-temperature reusable surface insulation (LRSI) tiles that can withstand up to 1,200 degrees Fahrenheit, while the black tiles are high-temperature reusable surface insulation (HRSI) tiles meant to withstand up to 2,300 degrees Fahrenheit, as detailed in a NASA paper from the mid-'90s. The color comes from a glass coating on top of the tiles, where white is used on the orbiter's upper surfaces to reflect light (and heat) back in the day phase of orbit, while black goes on the bottom surfaces for maximum emissivity and heat rejection during re-entry.

Not seen are the fibrous refractory composite insulation (FRCI) tiles, which were initially limited to isolated areas on the shuttle, but in later years used to replace both LRSI and HRSI tiles. RSI tiles were made of three different substrate materials: LI-900 and LI-2200, where LI stands for Lockheed Insulation and the numbers designate density, as well as FRCI-12, which has a density of 12 PCF. LI-900 is made of over 99% purity amorphous silica glass fibers, withstanding heat up to 2,200 degrees Fahrenheit. Most of the black tiles at the bottom of the orbiter use this material.

LI-900 is not very strong, so LI-2200 was developed for those areas of the orbiter that need strength; it's nearly identical in composition to LI-900, but adds silicon carbide powder. FRCI-12 is almost identical to LI-2200, though it adds alumino-boro-silicate "Nextel" fibers, according to the space agency. After 1996, FRCI-12 tiles were replaced with Alumina Enhanced Thermal Barrier (AETB-8) tiles, which added a small quantity of alumina fibers, and with a new coating produced a toughened unipiece fibrous insulation tile with higher impact resistance.

How Space Shuttle tiles are made and put together

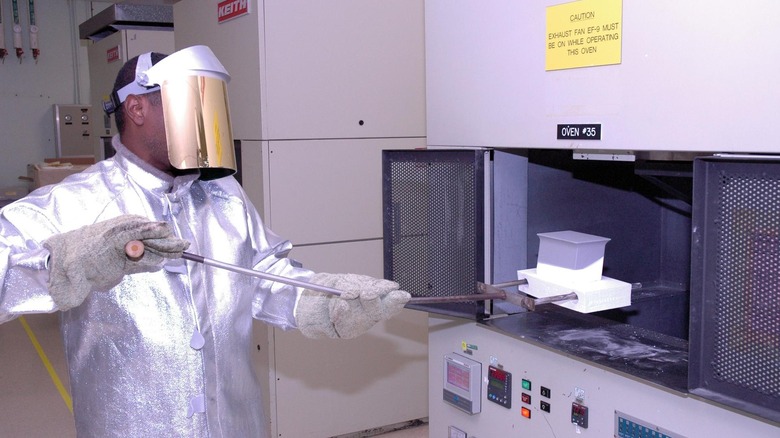

NASA explains the RSI tiles of the Space Shuttle began their manufacturing journey from refined sand silica. After fibers were formed and various chemicals were added, the material was poured into molds and then machined into the precise shape of the tile (no two tiles have the same shape), and then sintered at very high temperatures to activate ceramic bonding to fuse the fibers. Then, white or black glass coatings are sprayed onto the tiles, which are then fired in a kiln at 2,200 degrees Fahrenheit for 90 minutes. Tiles vary in size from 6 inches per side to 8 inches per side, and range in thickness between less than 0.5 inches to up to 5 inches.

The tiles are bonded to the orbiter using strain isolator pads and room-temperature vulcanizing silicon adhesives (SIP and RTV). Gaps between tiles have a filler bar below that can withstand 800 degrees Fahrenheit, allowing for thermal expansion — and where required, the gaps are filled with gap filler. The overall shape or outer mold line of the Space Shuttle Orbiter is determined by how well the tiles and blankets are placed, and the smallest imperfection could lead to a major disaster.

Apart from tiles, NASA also used larger swathes of insulation material it called felt reusable surface insulation (FRSI) blankets (up to 30 inches per side) meant to protect surfaces that aren't heated beyond 700 degrees Fahrenheit. In later years, advanced flexible reusable surface insulation (AFRSI) blankets were used to replace most LRSI tiles on the upper surfaces. Those are made of pure silica felt sandwiched between silica fabric and S-Glass fabric. It is bonded directly to the airframe, and then coated with high-purity silica.

Replacement and maintenance of Space Shuttle tiles

With roughly 24,300 tiles and 2,300 flexible insulation blankets used in the TPS design, it is no surprise that after each shuttle flight, there was a large downtime to assess, repair, or replace the parts involved: it took four to five months to complete preparations for the next flight. While improvements in TPS design, materials, and repair processes reduced the maintenance time, an average of 125 compromised tiles were still replaced after each mission. The tiles would also have to be re-waterproofed after each mission. The parts of the Space Shuttle Orbiter that experienced the greatest friction during re-entry, including the wings' leading edges and nose cap, were made of reinforced carbon-carbon panels, which can withstand temperatures over 3,000 degrees Fahrenheit.

Before each mission, the orbiter's RCC panels underwent three inspections to ensure their integrity, and if any damage was seen, the panel was removed and sent to the vendor for repair. A total of 135 NASA Space Shuttle missions were flown, from the maiden orbital flight of the Columbia in 1981 to the last flight of the Atlantis in 2011. Even though certified for 100 missions, the three most-used orbiters — Discovery, Atlantis, and Endeavour – completed only 39, 33, and 25 missions, respectively, by the end of the program. The Challenger flew 10 missions and Columbia flew 28 missions before their loss on January 28, 1986, and February 1, 2003, respectively.