Here's How Columbia Went From Sportswear To Spacecraft

Columbia Sportswear is one of the world's most well-known and recognizable sports and outdoor apparel brands. You'll find their gear at several familiar retailers including Bass Pro Shop, REI, and their own brick-and-mortar stores. Columbia offers everything from shoes to hats and clothing for all points in between, to keep you warm and protected even in the harshest conditions our planet offers.

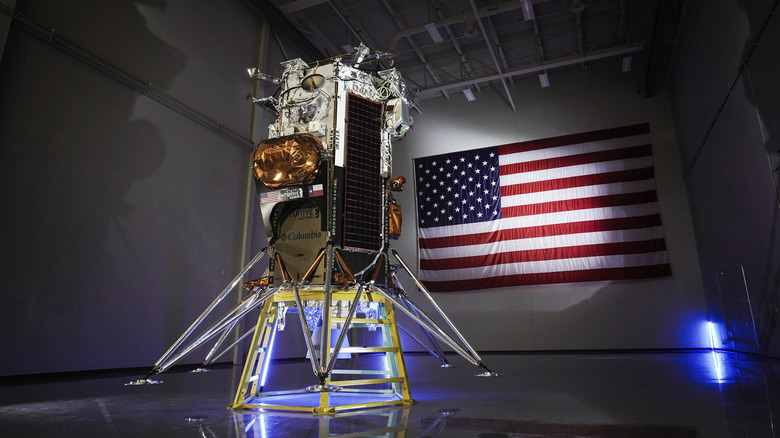

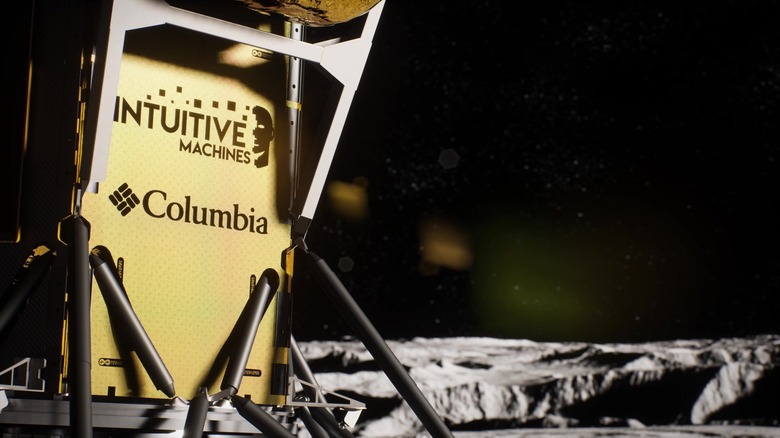

Now, Columbia is taking its outdoor gear to one of the harshest environments of all: outer space. Columbia has partnered with Intuitive Machines, a publicly traded American aerospace company based in Houston, Texas, to provide materials for an ongoing slate of spacecraft. The upcoming IM-1 mission will carry Intuitive Machines' Nova-C lander to the Moon's south pole and Columbia is going along for the ride in a big way.

Once on the surface of the Moon, the lander will be exposed to intense temperatures ranging from sweltering heat during the Moon's two-week daytime period to incredible cold during the lunar night. To keep it protected throughout the mission, the lander is headed to the Moon wearing what is essentially a Columbia jacket turned inside out.

Here's how that happened.

Humble beginnings as a Depression-era hat distributor

By 1937, Germany had become a horror show for anyone who didn't fit a narrow prescription of personhood. Husband and wife, Paul and Marie Lamfrom fled Germany along with their teenage daughter Gert, arriving in Portland, Oregon where they started a new life and a new company.

The duo purchased an existing hat business, renamed it the Columbia Hat Company in honor of a nearby river, and started distributing hats under Paul's leadership, in 1938. Gert later married a man named Neal Boyle who took over leadership of the company from Gert's father. When Neal died of a sudden heart attack in 1970, Gert stepped in to fulfill the family legacy.

Gert Boyle ran Columbia as the company's CEO and later as chair of the board of directors until she died in 2019. By then, Columbia had grown from a small hat distributor in the Pacific Northwest to one of the leading names in outdoor apparel. Though she may not have realized it, the innovations achieved during her tenure would ultimately take the company quite literally out of this world.

Columbia Sportswear comes into its own

For more than two decades, the Columbia Hat Company focused on the distribution of headgear designed and manufactured by other companies. In 1960, however, the company shifted gears from distributing products to creating their own after becoming dissatisfied with the products they were receiving from suppliers.

After shifting to a more expansive range of outerwear, the company's breakout product was a fishing vest complete with a magnet for holding flies. It's those sorts of simple innovations, thinking through what consumers need from outdoor clothing, that would come to define Columbia.

Around the same time that Columbia was rethinking its identity and business model, the then-fledgling field of space exploration was growing legs and racing for the Moon at full sprint. While the folks at Columbia were imagining new coats and gloves, engineers on the other side of North America were imagining how to get human beings off-planet and return them home safely. Gert Boyle probably couldn't have known it at the time, but the space race would eventually become a relay race and Columbia Sportswear would have an opportunity to help carry the proverbial baton.

Spaceships need jackets too, sort of

Spacecraft and astronauts operating outside the protective bubble of Earth's atmosphere are similar to wilderness campers and mountain climbers in one important way. If they can't stay within a defined temperature range, they might die. To that end, NASA developed the "space blanket" in 1964, to support its ongoing space activities.

Despite the common belief that space is cold, that's only true some of the time. In the near-vacuum of translunar space (the space between Earth and the Moon) there aren't many molecules and absolutely no wind to help carry heat away. Any heat generated by a spacecraft's electronics or collected by exposure to the Sun can't be cooled through convection and has to radiate away slowly. It's the reason the International Space Station (ISS) has such massive radiator arrays.

When developing those early spacecraft, NASA needed a thin, flexible, and lightweight material capable of regulating the temperature around and inside a craft, and the space blanket fit the bill. Since its invention, space blankets have been used on everything from orbiting telescopes like Hubble and the JWST to ISS, the Cassini spacecraft that visited the Saturn system, and the Apollo Lunar Module that carried astronauts to the surface of the Moon.

What are space blankets?

Space blankets are also sometimes called emergency blankets or thermal blankets and you've probably seen them inside first aid kits or wrapped around athletes after a performance. Space blankets are one of the most ubiquitous inventions of the space race, having made their way into many facets of everyday life. Today, the same material is used for thermal control inside computers and houses, according to NASA, in addition to protecting practically every spacecraft you've ever seen.

Check out any satellite, probe, lander, or rover and you'll see shiny gold or silver material wrapped around specific spots or components. The location and orientation of space blankets are carefully determined to regulate temperature, depending on the environment it will be working in. The space blanket game plan for a Mars rover, for instance, will be different from a probe headed for Pluto.

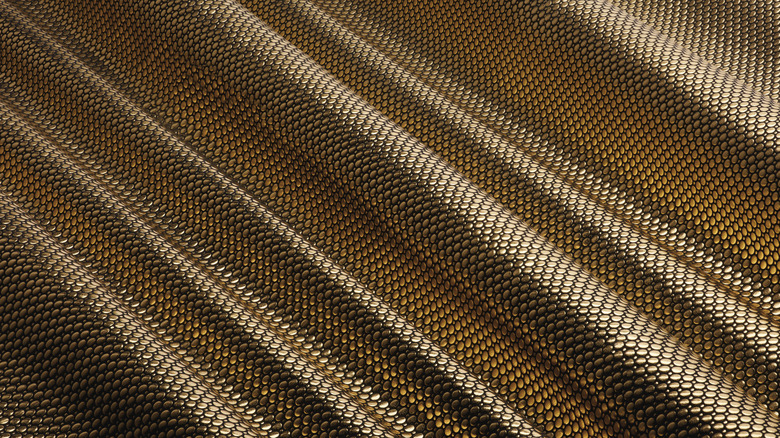

Space blankets are constructed by sticking vaporized aluminum to the surface of a thin sheet of plastic. The resulting fabric is light enough to only minimally impact the launch weight of a spacecraft while providing incredible thermal control. Space blankets are typically used to reflect infrared radiation, the primary delivery system for heat in space, away from a spacecraft to keep it cool. However, they can be made and oriented in such a way that they hold heat in, to warm a spacecraft passively.

NASA's space blankets inspired innovation at Columbia

After the turn of the millennium, Columbia started playing around with the idea of incorporating space blanket technology into its outerwear. NASA technologies have a way of filtering into the commercial sphere and the homes of consumers, and space blankets are no exception. The idea was to use the same technology that bounces heat away from a spacecraft, turn it inside out to face the body, and use it to keep heat trapped. That endeavor eventually led to Columbia's Omni-Heat line of outerwear, which debuted in 2010.

"The stuff we've had for over 10 years in the product line was originally inspired by the NASA space blankets used in the Apollo missions," Haskell Beckham, Columbia's VP for Innovation, told SlashGear. "The key component is the metal. Metals have this fundamental property that they reflect heat. In the case of outerwear, you're reflecting your body heat. In the case of the lander, you're reflecting the heat coming from the Sun, so it's serving the same purpose."

Columbia took that idea of reflecting radiant heat and they tucked it inside boots, gloves, coats, and hats. While the underlying principle is sound, there are some pretty major differences between a spacecraft and a person, so Columbia had to make some adjustments to their material to account for biology.

Spaceships don't sweat, but people do

Space blankets were designed to protect machines and orbital collections of metal and plastic with a distinct lack of pores and glands. The major challenge in making a jacket or gloves out of a space blanket is that the material is too good at reflecting heat. An unbroken piece of aluminum-coated plastic is great for trapping heat but it isn't at all breathable. That's a problem if you're warm-blooded and constantly generating heat.

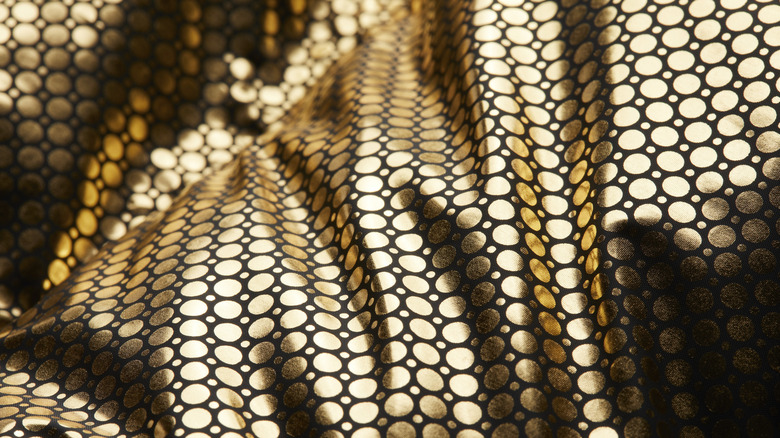

To get around that issue, Columbia arranged its thermal-reflective material into a series of dots mounted to a thin piece of conventional, breathable fabric. If you imagine a checkerboard covered in-game pieces, you'll have a pretty close approximation. This arrangement of dots provides significant coverage from the reflective material while offering plenty of openings for breathability. "It's that black fabric that lets the moisture coming off your body out, so it is breathable. Obviously not important on a spacecraft, but it is in a jacket," Haskell Beckham said.

In the years since Columbia first introduced Omni-Heat, the company has gone through several iterations, including Omni-Heat Black Dot. While the internal Omni-Heat layer reflects heat from your body, Black Dot soaks up sunlight to warm your jacket from the outside. The key to the Omni-Heat line is taking space-age materials and modifying them to better serve humans here on Earth.

Commercial space exploration kicks off

For decades, space exploration has largely been the purview of large government agencies. The barriers to entry were just too great for anyone else to get a toe-hold. That's all changed in recent years. Companies like SpaceX and Blue Origin are already flying passengers on private and public space missions, and those aren't the only companies that want a piece of the Moon pie.

Enter, Intuitive Machines, a commercial aerospace company founded in 2013. As NASA prepares to return humans to the Moon under the Artemis program, it has partnered with commercial entities under the Commercial Lunar Payload Services program. Under CLPS, private companies are responsible for the design, construction, launch, and operation of their respective crafts. They receive funding from NASA and, in turn, carry NASA payloads to further the agency's lunar science and exploration goals.

In 2018, Intuitive Machines was selected as one of three companies, alongside Astrobotic and OrbitBeyond, to build and launch the first U.S. lunar landing missions since Apollo 17. Intuitive Machines was awarded $77 million in funding to support its Nova-C lunar lander.

IM-1: The maiden flight of Intuitive Machines' Nova-C

The Nova-C lander from Intuitive Machines is scheduled for launch from Cape Canaveral, Florida in mid-February of 2024, barring further delays. The mission was originally slated for November 2023, riding aboard a Falcon 9 rocket. SpaceX and Intuitive Machines bumped the launch to a later February launch window, citing poor weather which changed SpaceX's flight schedule.

IM-1 will be the first of three contracted flights for Intuitive Machines, each of which will build upon lessons learned from previous missions. As part of the arrangement with NASA, IM-1 will carry six NASA payloads along with several commercial (and sometimes secret) payloads. NASA operations are publicly funded and, therefore, the nature of the payloads is public information. Private companies don't have the same requirements.

The NASA payloads include experiments focused on how lander engines interact with the lunar surface, communications, and radio astronomy, to name just a few. Among the non-NASA payloads is the EagleCam from Embry-Riddle University. "I love all my children," Ben Bussey, Chief Scientist for Intuitive Machines, told SlashGear before describing one child (payload) he likes more than others. "EagleCam is a camera that is going to get ejected before we land and take pictures. That's exciting!" IM-1 will also fly the International Lunar Observatory, a precursor to a proposed moon-based radio telescope on the Moon's far side.

Keeping the lander the right temperature

When it came time for Intuitive Machines to figure out how to protect its Nova-C lander from the extremes of the lunar environment, they looked to a commercial partner for help, and Columbia answered the call. Engineers from both companies got together and realized that a lot of their requirements, expertise, and goals were aligned, despite the dramatically different operating theaters.

"We've been working with them [Intuitive Machines] since 2021," said Haskell Beckham. "When we started talking to them we realized we spoke the same language in terms of insulation, and that the proprietary thermal reflective insulation we used in our outerwear could potentially be used in a lander to help protect it from the extremes of outer space."

Of course, Columbia had made modifications from the original NASA space blanket material and it wasn't immediately clear that the company's Omni-Heat tech would be suitable. "It is slightly different from the materials they usually use for spacecraft," Beckham said. "We did lots of lab testing at both really low temperatures and high temperatures to make sure it would be durable enough."

Engineers from both teams worked in tandem, trading notes and materials to land on the finished product.

Wrapping the Nova-C in a Columbia jacket

Since Omni-Heat is designed for humans on Earth, and not for spacecraft on the Moon, there was some suspicion that they might need to make modifications to meet the needs of the lander. That turned out not to be the case.

"When we first started talking to them we were completely prepared to modify what we were already doing. We'd had thermal reflective insulation in our outerwear for over ten years, and after we did lab testing and thermal modeling, we realized we could actually use the same exact material that's in our jackets," Haskell Beckham said. Put simply, Intuitive Machines built a lunar lander and Columbia wrapped it in a jacket (specially tailored, of course) to keep it temperature controlled. "In hindsight, it probably shouldn't have been too surprising that we could use the exact same material, because the material we use was originally inspired by NASA," Beckham said.

Instead of wrapping the entire lander, engineers from both companies worked together to determine the most vital spot. In the end, they targeted a particular panel at the front of the lander where the thermal reflective heat shielding would do the most good on the Moon. It's easily identifiable by the Intuitive Machines and Columbia logos printed over the top of the gold-spotted panel.

IM-1 has already inspired better Earth jackets

Columbia is readying for its first journey into space aboard IM-1 and it won't be the last. Columbia and Intuitive Machines are already contracted to work together on IM-2, which is currently in construction at Intuitive Machines' headquarters in Houston.

During a recent media event, representatives from Columbia were present, in part, to deliver new materials for possible integration into IM-2. Those materials might eventually make their way to your coat rack. Already, the development of IM-1 has given rise to new innovations and products. Just a few weeks before the last bolt was tightened on IM-1, Columbia released the Arch Rock Double-Wall jacket which features a new construction directly inspired by IM-1.

"We've already learned so much through this partnership," Andy Nordhoff, Columbia's Director of Communications, told SlashGear. "We learned from the Intuitive Machines crew that they are layering the reflective insulation."

Columbia took that knowledge back and incorporated it into the Arch Rock jacket. "Instead of just one layer of insulation, we've incorporated a second into the shell. It doesn't impede breathability but it certainly ups the level of warmth," Nordhoff said.

The Nova-C lander is a case study of the modern space economy

A common complaint orbiting around space exploration is that the price tag for even a single mission is high, with no obvious and immediate payoff for the folks back here on Earth. The legacy of space blankets pretty soundly proves that isn't the case, and that's just one example. Water purification systems, wireless headphones, and modern baby formula can all trace their existence back to NASA innovations. Columbia's Arch Rock Double Wall jacket is only the latest in a long line of familiar products originally designed for space, and that sort of innovation both at home and off-world is exactly what NASA was hoping for with its Commercial Lunar Payload Services program

Moreover, there's a sort of self-reinforcing relationship at play. NASA's space blankets inspired the first generations of Columbia's Omni-Heat material. That material is now mounted to a spacecraft itself and headed for a permanent spot on the Moon, and the process of preparing for that trip has already led to new consumer products even before launch. Lessons learned during the flight and surface operations of IM-1 will likely lead to even more innovation and improvement which Columbia will take back to the sewing machines.

Every step along the way informs the next and humanity ends up with better spacecraft, a clearer path to a permanent human presence on the Moon, and warmer jackets in the process.