10 Extinct American Car Brands You Might Not Have Heard Of

Like a game of corporate musical chairs, the question of who owns and produces which car brand has delighted and preoccupied car nuts for decades. With a handful of international corporations now clutching most of the world's historic brand names, it's easy to forget the bygone days when your car might have been built just around the corner.

The corporate family tree of automobile producers during the 20th century equates to an interconnected jungle that merges and diverges, wending through the challenges and triumphs of the free market in the 21st century. Today, dozens of historic and storied brands shelter beneath the umbrellas of huge conglomerates like Volkswagen and Stellantis.

These are the survivors, and there aren't many of them left. Once, the market was crowded with young, innovative brands eager to put their name in the automobile game. Many have been erased from the market, but not from memory. The scrapyards of time are littered with the infamous and beloved automobile brands of yesteryear.

De Soto

Walter P. Chrysler named this new branch of his corporation after the conquistador Hernando de Soto, reportedly after perusing a history book. Whatever the origin behind this name, Chrysler aimed its new De Soto line at the middle class, firing its first salvo with the 1929 De Soto Six.

Despite launching the same year as the Great Depression, De Soto stayed in business. The De Soto Six sold over 81,000 units — a first-year sales record that would stand for 31 years. The 1934-1936 De Soto Airflow dulled enthusiasm, but a redesign for 1939 and a foray into military production, building Sherman tanks during the Second World War, kept the factory humming. By the time the war ended and industry returned to civilian life, De Soto was poised to take a bite out of the thrumming American economy.

Reverting to auto production after the war, 1946 brought reskinned 1942 models to the modern streets of America. De Soto launched the Firesweep, Fireflite, and Firedome. Those carried De Soto into the rocket-inspired fin designs of the 1950s, but that was where it began to come apart. Issues with quality control and competition from Ford, General Motors, and even Chrysler squeezed De Soto out of the game. Its final model rolled off the assembly line in 1961. Unfortunately, the downward spiral of De Soto relegated the brand to the dustbin of American industrial history.

Pierce-Arrow

Everyone knows the Great Lakes' Rust Belt for its long-suffering football fans and a history of building classic American vehicles, but few think of the city of Buffalo, NY. And yet, this is where you'll find the origin of Pierce-Arrow, a legend amongst defunct American autobuilders. Like many automotive pioneers, George Pierce began a career in manufacturing, beginning with tinware before graduating to bicycles. Experimentation drove the company to develop six steam cars in 1900. The following year, Pierce sold 25 new and improved four-cylinder internal combustion-powered Pierce Motorette automobiles for $850 apiece. Pierce eventually introduced the Arrow, later incorporating it into the company's name.

George Pierce left the equation when Studebaker purchased Pierce-Arrow with a plan to launch a luxury line. Part of Studebaker's strategy included a new eight-cylinder engine that helped it become a contemporary competitor of the likes of Rolls-Royce, Cadillac, Duesenberg, and Mercedes. His vision would pay off when a Pierce-Arrow served as the American president's first official vehicle.

Owning a Pierce-Arrow was a status symbol in the early days of automobiles. Studebaker sold the firm to a group of Buffalo businessmen in 1933. Unfortunately, Pierce-Arrow would go out of business just 5 years later in 1938, unable to withstand the economic ravages of the Great Depression.

Kaiser-Frazer Motors

Kaiser Motors didn't come into existence until 1945, right at the end of the Great Depression and the Second World War. Before then, Kaiser made his fortune in shipbuilding. Relatively late to the automaking party, he pitted his new company against the Big Three, already well established in Detroit. With former Chrysler executive Joseph Frazer serving as president, the new company aimed to push out two new models in 1946: the Kaiser and the Frazer.

Operating first out of a former B-24 Liberator plant previously operated by Ford, Kaiser introduced several new vehicles over the next few years. The Traveler and Vagabond came and went between 1949 and 1953. Basic four doors and family-friendly convertibles were the name of Kaiser's game. Unfortunately, seeing the future was not.

Kaiser met an ignominious end when the partnership with Frazer flared out. The experienced Frazer proposed reduced production in the face of a wave of new releases by competitors, while Kaiser insisted on gearing up for mass production. The company's namesake had its way, resulting in a $39 million loss. Frazer left the company in 1951, which disappeared from the market by 1955.

American Motors Corporation

The American Motors Corporation began as the 1954 fusion of the Nash-Kelvinator Corporation and the Hudson Motor Car Company. George Romney, perhaps more famous today for siring Mitt Romney, took the helm as president. He launched AMC on a mission to fill the compact car void neglected by the Big Three.

Though initially aiming at the compact market, AMC was around long enough to tend to the trends of the day. One of which, the muscle car revolution, produced what some consider AMC's high point in the 1970 AMC AMX 390. Powerful, stately, and hitting all the proper strokes in one of automaking's most fondly remembered design periods, the AMX may not have the cache of the Ford Thunderbird or the power of the Chevelle SS, but it was still more than an also-ran.

The Malaise Era took its toll on AMC, which limped through the 1970s and into the 1980s, persevering until Chrysler snapped it up, marking the end of a 34-year run building distinctly American vehicles that achieved varied levels of fame. Nameplates like Rambler, Pacer, Gremlin, and AMX wove into the fabric of American culture between 1954 and 1988, when AMC shuttered its doors.

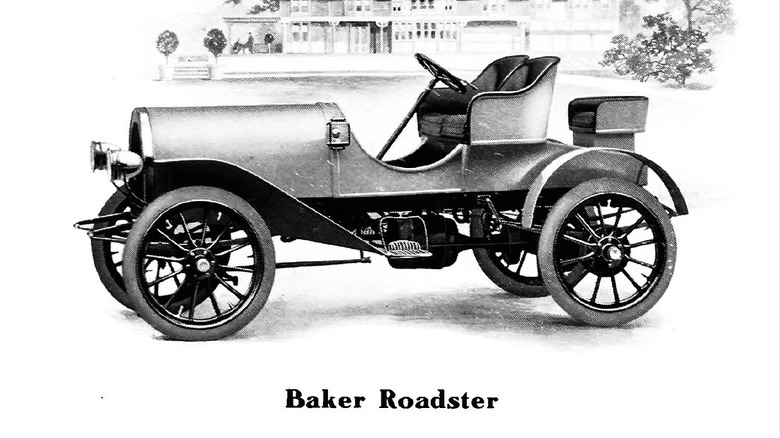

Baker Motor Vehicle Company

Once upon a time, no one knew which revolutionary technology would carry automobiles into the future. Could it be the internal combustion engine or the electrically-powered motor? If ever there was a case for history repeating itself, the evidence may lie with the Baker Motor Vehicle Company.

Engineer Walter C. Baker and associate F. Philip Dorn built an electric vehicle in 1897, the infancy of automobile development. By 1899, they incorporated a manufacturer that would make electric carriages that moved as if by magic. The 1901 Baker Electric runabout was more carriage than car, with widely-set wheels and a seat mounted on a flat platform. Rudimentary as it may seem, there was a kernel of the future in the Baker. The automaker's personal race cars hinted at more of that future.

Baker was many things: The scion of an industrial fortune, co-founder of multiple successful businesses, but also a devoted car-racing hobbyist. Sculpted to a Jules Verne vision of aerodynamics, Baker developed the Electric Torpedo and a pair of Torpedo Kids, powered by lead-acid batteries, and annihilated the existing land-speed record of 75 mph with 100 mph runs at Staten Island, New York. By 1906, Baker had reached its apotheosis, counting itself among the world's top auto producers. By 1915, it was finished, another victim of the whimsy of vehicle manufacture.

American Austin Car Company

The luxury barges of the old days get plenty of attention, making it easy to overlook the oft-forgotten economy cars of the '20s and '30s. English marque Austin introduced the tiny Austin Seven in 1922, and the formula was a hit. Soon, BMW was licensing the design, while Datsun and others took strong inspiration for their own models.

Austin signed a license for American production of its diminutive hit in 1929. Production spooled up in an unused railcar plant in Butler, Pennsylvania. The American Austin was positively tiny compared to the Fords of the era. A wheelbase of 75 inches and a track width of 40 inches were part of the charm that attracted drivers in England, and a 45.6 cubic inch engine produced 13 horsepower. American Austin innovated with body styles including a roadster, coupe, and open and closed setups for commercial use.

The American Austin hit the roads in 1930 and sold 8,000 units in its first year — a respectable number. However, that was the high point for the company. Within 2 years, competition in the segment, combined with the novelty of the Austin wearing off, tanked the company. It shut down production in 1932, resumed in 1935, was purchased, and survived into the 1950s as American Bantam before giving up the ghost.

Hudson Motor Car Company

The early 20th century was open season for automakers. Dozens of companies flared into existence only to be consumed by the floodwaters of competition. Barriers to entry were high, but that didn't stop Joseph L. Hudson, a department store proprietor and Detroit industrialist, from funding the incorporation of the Hudson Motor Car Company on February 20th, 1909.

Hudson was, more or less, the money behind the vision of Roscoe B. Jackson, who teamed with Roy Chapin and engineer Howard Coffin to design the factory and vehicles. Hudson sold 4,000 four-cylinder models in its first year. Within a few more, it was producing 100 cars a day at a steady clip. Hudson grew into a new factory and released the Super Six — a six-cylinder engine that overpowered its previous offerings. It helped push Hudson to its zenith, producing 300,000 cars in 1929. More new technology would follow. Hudson introduced the Electric Hand Transmission, a troubled example of an early automatic transmission that paved the way for future versions, but wouldn't save Hudson.

Hudson survived the Depression and the 1940s, emrgin with Nash-Kelvinator in 1954 to create the American Motors Corporation. Even in that evolved form, any scrap of Hudson's existence ceased when AMC itself rolled into Chrysler in 1984.

Studebaker

Many automakers started life before automobiles were even a thing, but Henry and Clement Studebaker opened their first blacksmith shop in South Bend, Indiana, in 1852. Studebaker spent years producing covered wagons for the U.S. Army and anyone else who wanted to settle in the American West. The company was already half a century old when it sold its first electric vehicle, in 1902.

By 1910, the Studebaker Brothers Manufacturing Company had halted electric vehicle production and purchased a Detroit company to become the Studebaker Corporation. It hit through the 1920s with its Big Six model. A declaration of bankruptcy in 1933 gave the company the time to reorganize and continue operation through the Depression. Studebaker innovated through the 1940s with improvements to transmission, steering, and braking systems. It built cargo trucks and the iconic Wright Cyclone radial engine that went into the B-17 Flying Fortress during the Second World War. From covered wagons to Allied aircraft, it's hard to argue against Studebaker's place in American history.

So why did Studebaker fail, anyway? A company that transitioned from covered wagons to aircraft engines ought to be able to weather just about anything. The downslope began when management opted to pay larger dividends to happy shareholders rather than preserve capital. All seemed well until an economic dip in the mid-1950s drained the coffers. Combined with an aggressive union that demanded and received the highest rates in the industry, Studebaker stuttered into the next decade before dying in 1966.

Saturn

Millennials may remember the buzzy new miracle brand Saturn. General Motors launched the brand in 1991 with the mandate to regain market share lost to compact imports. Though ultimately doomed, Saturn made a fight of it for nearly 20 years before succumbing to circumstances in 2010.

The Saturn story goes back to 1982, when GM head Roger B. Smith greenlit an idea from the company's advanced engineering and manufacturing departments. Not just a new brand, but a new kind of manufacturing: Plastic bodel panels bolted onto steel frames were easier to paint, engine components that required less fine machining, and a modern inline four-cylinder that was a step out for GM at the time, but enjoyed success in Honda and Toyota form.

Saturn hit the ground running. With GM's rich supply of bin parts and clever manufacturing, from SUVs in the Saturn Vue to sports cars in the Saturn Sky. In between, a plucky assortment of sedans and wagons plugged gaps in the market, making Saturn a full-spectrum manufacturer in its own right. But success doesn't last forever. The exigencies of the 2007 financial crisis and continued imported dominance struck the death knell for Saturn.

Packard

Packard was born in 1899 when Packard brothers James Ward and William Doud established a company in Warren, Ohio, and named it, of course, the Ohio Automobile Company. Shortly after, they renamed it Packard and moved to Detroit.

The brothers wasted no time developing what many claimed but few achieved: quality performance vehicles. Packard's 1904 Grey Wolf race car was the first to break the nearly mystical mile-per-minute barrier when it hit 60 mph. Developing the Grey Wolf may have pushed the tech, but Packard settled into a steady thrum, producing more prosaic vehicles like delivery trucks.

Yet the company's ambitions remained high. In 1915, Packard introduced its famous Twin Six engine — known now as the V12 — that propelled many luxury performance cars until the Second World War, when the company built Merlin engines for P-51 Mustangs. Struggling in the ultra-competitive post-war market, Packard merged with Studebaker in 1953. The Studebaker-Packard Corporation didn't work out, closing factories in a rearguard action before bowing out in 1958.