Common Air Force Ground Crew Hand Signals And What They Mean

If you've ever looked outside an airport window while waiting for your flight to get underway, you've probably noticed the ground crew using hand signals. These hand signals are not just a means of communication; They're a potential lifesaver. In many organizations and communities — from military ground forces to motorcycle riders – hand signals are used to explain complex procedures and indicate intent across distances. In combat situations, where vocal communications could alert the enemy, hand signals can be the difference between life and death.

The operating area of an airfield, where aircraft are loaded, fueled, maintained, moved, or operated, is a dangerous and exacting environment. Aviation engines are extraordinarily loud, and the distances involved in maneuvering aircraft often preclude verbal communication. Raising the stakes is the fact that even the slightest miscommunication can lead to the loss of millions in equipment or even lead to a fatal accident.

Those stakes are even higher on military airfields. The high-tempo operation of heavily armed and fully-fueled aircraft requires the cooperation of specialized and trained troops. Air Force personnel are highly trained in hand signals that allow them to control an airfield during peace and war. Today, we're diving into the official training manuals of the United States Air Force to find out how ground personnel execute safe airfield operations using only their hands.

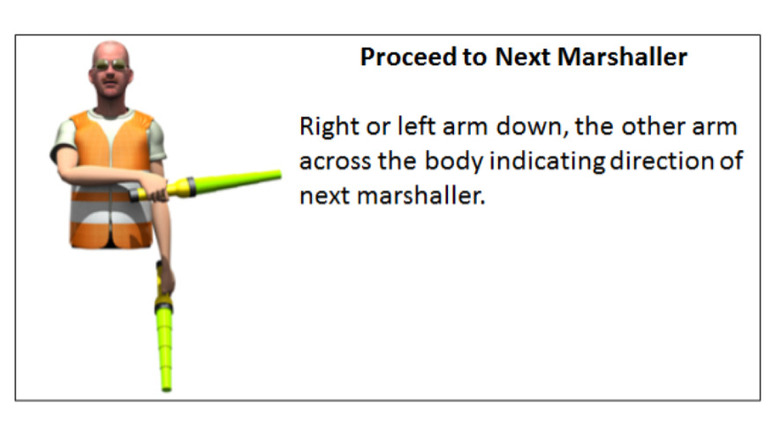

Proceed to next marshaller

Pilots may enjoy a bird's-eye view when aloft, but their birds are much more unwieldy on the ground. The expansive spaces of the sky are far less restrictive than a busy and crowded airport tarmac, and military aircraft account for some of the largest planes in the world.

Airfields, including those of the United States Air Force, count on ground personnel known as marshallers to direct air crews to where they need to be for the next phase of operation. Air Force regulations require that marshallers wear a reflective vest and use a specialized piece of equipment known as a marshalling wand to improve visibility. You've probably seen them at the airport or on television. They look like a cross between a flashlight and a lightsaber, making it easy for aircrews to see what the marshaller indicates.

Marshallers can be a single link in a chain, resulting in a series of connect-the-dot-style steps that allow an aircraft to move safely to where it needs to be. Think of a marshaller as a sort of traffic cop, making sure everything is safe and punctual. To send an aircraft along to the next marshaller in line, an airman places the left or right arm down and holds the other arm across the body, pointing in the direction the aircraft needs to go with the marshalling wands.

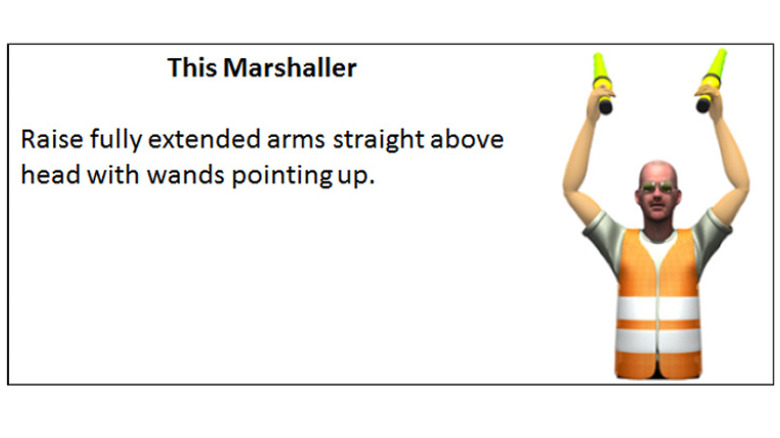

This marshaller

If a marshaller is in the position where the aircraft is supposed to hold, whether it is its final destination or merely a temporary rest, there is a special motion to indicate that. The marshaller will raise extended arms overhead with the marshalling wands parallel and pointed toward the sky.

In certain situations, aircraft need to occupy precise positions on the tarmac. This may be to use specialized technical equipment, such as refueling trucks or auxiliary power units (APU), or to offload cargo or personnel.

Whatever the case, the marshallers have a front-row seat to the plane's ground position that may not be available to the air crew. The ground crew can indicate to the pilot that the aircraft needs to adjust its location slightly to attain proper positioning.

From this position, a marshaller will move their hands up and down from shoulder to head height to indicate that an aircraft should move forward. To suggest a left or right repositioning, the marshaller will continue the motion while using the other hand to point in the corresponding direction. Once an aircraft is in the proper position, the marshaller extends the wands at a 90-degree angle to the body, then crosses them overhead.

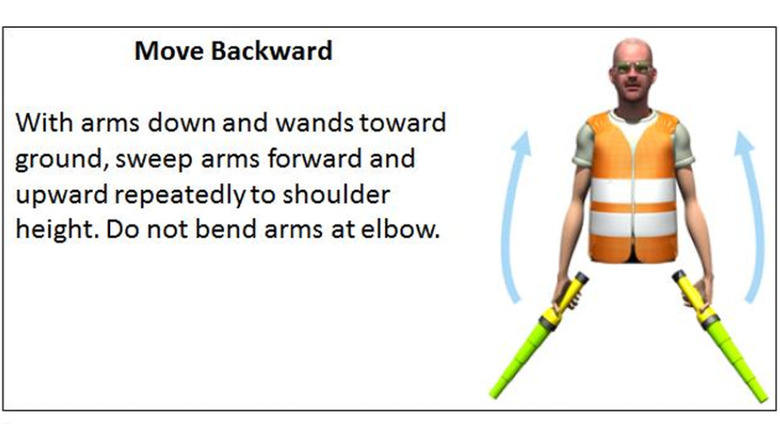

Move backward

If navigating an aircraft across the tarmac is a daunting proposition, moving one backwards is even more so. While most fourth- and fifth-generation fighter jets are relatively small and offer incredible views via their bubble canopies, the Air Force operates more than just fighters. The largest aircraft in the USAF fleet is the C-5M Super Galaxy. At 65 feet tall, 247 feet long, and 222 feet wide, backing a Galaxy up is akin to maneuvering a six-story building into a parking space.

Marshallers aid the air crew in reversing into blind spots with a dedicated series of reversing motions. To indicate that an air crew must begin to back up, the marshaller extends straight arms toward the ground and repeatedly sweeps the wands from thigh to shoulder height.

An aircraft may also need to pivot while reversing. The marshaller will continue to perform the backward motion with one arm. They will then extend the arm in the direction the pilot is to take. All motions are performed to correlate with the pilot's point of view to reduce the chance of a misunderstanding.

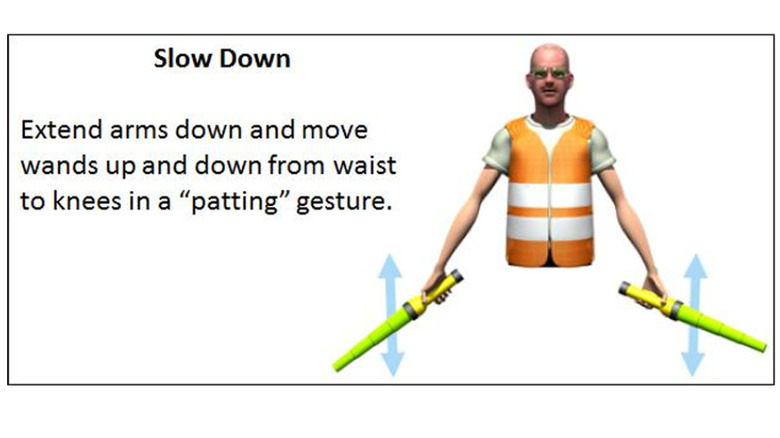

Slow down and stop

The operations on an airport apron are a delicate dance. At most military airfields, multiple aircraft are in motion at one time. Like automobile traffic, aircraft ground traffic may also need to slow down to increase safety or allow other aircraft to maneuver. A marshaller will communicate the need to slow down to the air crew by extending the wands out from the body at waist height. From here, they will move the wands up and down from the knee to the waist in a patting motion. It's the marshaller's equivalent of telling your buddy to pump the brakes from across the bar.

In the case of multi-engine planes, certain situations call for one side's engines to be slowed down. A marshaller can order this by leaving their arms down and waving either the left or right wand corresponding to the engine in the slow-down motion.

After all this maneuvering and marshalling, an aircraft will inevitably find itself in its proper position. If it is not prepped to take off, the air crew must know the job is finished. The marshaller will fully extend the arms at 90-degree angles and move the wands up until they cross. Marshallers can walk a plane into its stopping position by leaving the wands slightly apart and slowly drawing them closer together. When they make contact, the aircraft is in position and should come to a stop.

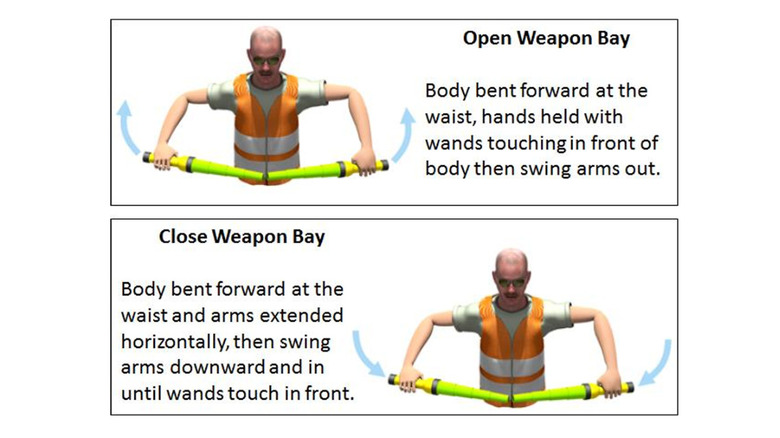

Open and close weapon bay

While civilian airfields and marshallers use most of these universal symbols for flight operations, some situations are reserved exclusively for the military. After all, you probably wouldn't feel safe taking that connector flight to JFK with thousands of pounds of bombs in the cargo hold.

Access to the weapon bay on the tarmac is a crucial requirement for Air Force personnel during specific situations. This is particularly significant as many next-generation military aircraft now house their weapons internally. A marshaller can signal the pilot to open the weapon bay by bending forward at the waist and holding the wands in front of the body before swinging them up and out to a straight-armed position. To close the weapon bay, the marshaller reverses the motion until the tips of the wands touch in front of the waist.

With a bit of imagination, one can envision the arms mimicking a pair of weapon-bay doors opening or closing. If you see this one from your window seat in first class, you may want to reconsider your trip.

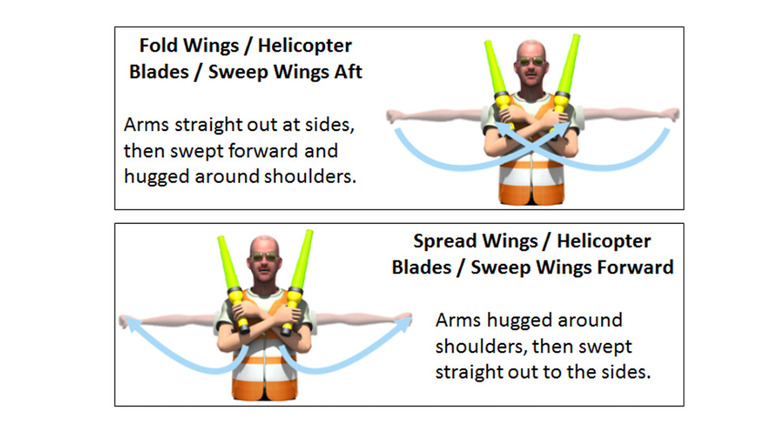

Fold and spread wings or blades

Many military aircraft have a function not commonly found on civilian aircraft in their ability to fold wings. While the U.S. Air Force does not operate aircraft carriers, aircraft that can fold wings — like the versatile Navy Grumman A-6 Intruder – can do so to preserve space in aircraft hangars below decks.

Since Air Force and Navy personnel must sometimes operate with sister services, airmen are trained in signaling how to tell a pilot to fold or unfold an aircraft's wings. To signal that the pilot should spread the wings, a marshaller begins with arms crossed, with the handles of the wand at shoulder height and the light portion extending above the shoulders. Swinging the arms straight out to the sides in a pantomime of a spreading wing completes the motion. Returning the arms to the original position is the signal to refold the wings.

When the wings or blades are in the preferred position, the marshaller may signal to lock them in place by raising the right hand and pointing the left wand to the right elbow. This is an essential step in securing aircraft for storage. Misunderstanding or failing to lock the wings in the proper position can create dangerous situations. One credible account of naval flight operations saw an A-7 Corsair II pilot accidentally take off with folded wings. He realized his mistake when the aircraft's controls felt heavy and was able to land safely, much to the astonishment of both onlookers and the engineers at Vought.

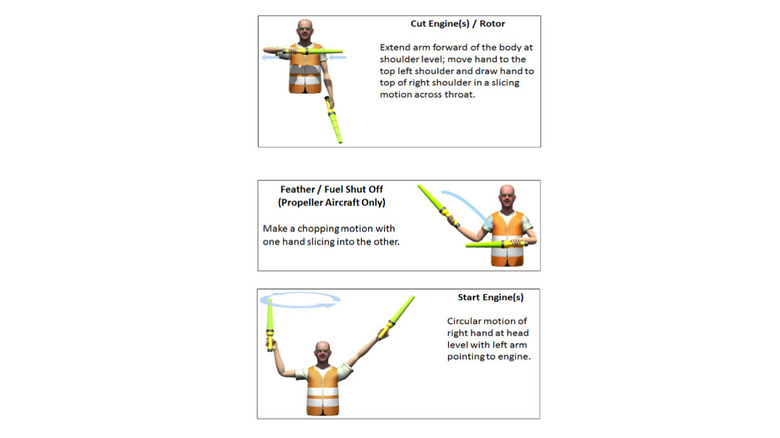

Start/stop engine

Starting up or shutting down an aircraft's engine is often a complicated process, and it differs from plane to plane. Many require external auxiliary power units (APU) to provide enough power to turn the massive engine over. When an aircraft is in the proper position and all checklists and criteria are met for a safe ignition, the marshaller will call for an engine start. They do this by raising the right hand to head level and moving the wand in a circular direction. The other hand will point to the engine that is supposed to start, a key concern in multi-engine aircraft.

Shutting down an engine is no less critical and can also be a complex task for the pilot. When the marshaller wishes to signal a shutdown, they will extend the right hand to the level of the left shoulder and pull it to the top of the right shoulder across the throat. Picture a throat-cutting gesture many use to tell someone to cut something out.

Propeller-driven aircraft perform a special operation known as feathering before start-up or shutdown. This involves turning the propeller blades to reduce drag and thus stress on the engine. Marshallers indicate a feathering by holding the left arm at waist level while the right arm comes down atop it from a 45-degree angle.

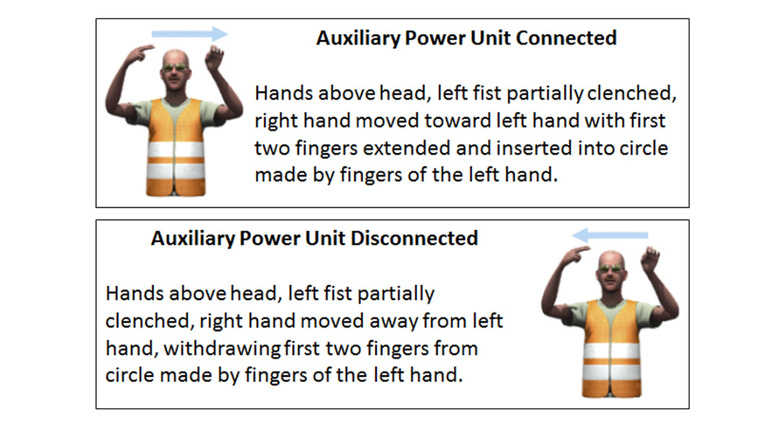

Auxiliary power unit connected/disconnected

Colloquially known as start carts, APUs are portable enough to maneuver from plane to plane and can be impressive power plants on their own. The high-flying SR-71 Blackbird spy plane originally used the AG-330 start cart, which consisted of a pair of 401-cubic-inch Buick V8 engines situated in tandem to get its J-58 engines started.

With such powerful units guiding the ignition of an aircraft, communicating an APU's status to the pilot is critical. Aside from having the potential to damage the plane, the improper use of an APU can result in injury or death. As such, marshallers have a specific motion to indicate to the pilot the status of the APU.

To let a pilot know that the APU is connected, a marshaller will hold the left fist partially clenched at head level. The right hand makes a pointing gesture with two fingers and inserts the fingers into the center of the fist, similar to how a plug would go into a socket. Communicating that an APU is disconnected is the opposite gesture, with the fingers of the right hand pulled out of the fist and back to their original position.

External air units are also often connected to and disconnected from aircraft, and the gesture is similar. The only difference is that the marshaller uses a cupped left hand, while the right hand is in a fist. Moving the fist into the cup indicates connection, while withdrawing shows disconnection.

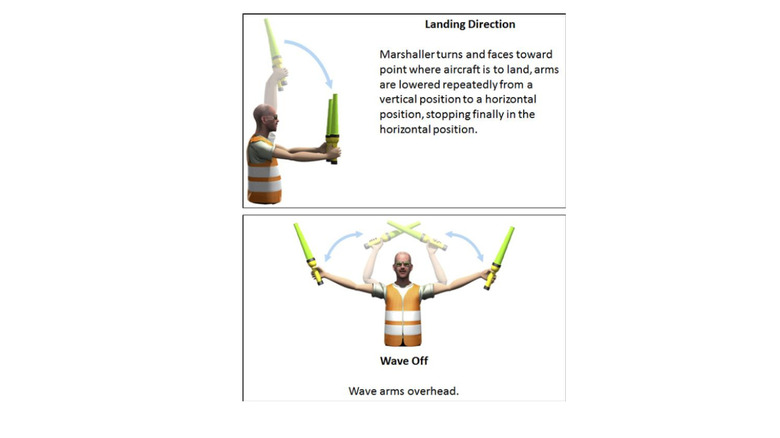

Landing direction/wave off

In certain circumstances, a marshaller can also convey important information to an aircraft on a landing approach. In this case, a marshaller (hopefully equipped with wands to improve their visibility) will face the direction in which the aircraft is supposed to land. Holding the wands overhead with an extended arm, the marshaller will repeatedly lower the arms to shoulder height, with the wands remaining vertical. This tells the pilot where the landing strip they should be aiming for is located.

Adapting to changing ground conditions or the aircraft's altitude and speed may necessitate a pilot to abort a landing and go around for another attempt. This is particularly prevalent on aircraft carriers, where the pitching and moving deck poses a significant challenge to pilots. In such situations, the marshaller becomes the final line of defense, with the crucial responsibility of calling off a landing if necessary. They do so by holding the wands overhead in a crossed position and then repeatedly moving the arms to the horizontal position.

Furthermore, a marshaller can provide supplementary guidance on the aircraft's direction. For instance, holding the arms out horizontally and repeatedly bending the left arm overhead while keeping the right arm straight communicates to the pilot to adjust the plane's position to the right. Conversely, a bent left arm and a straight right arm indicate the need for the opposite adjustment.

Emergency motions

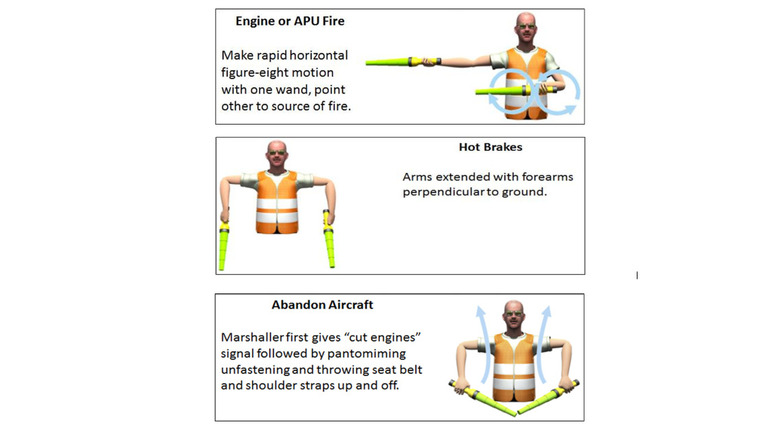

With the size of some aircraft, it is entirely possible that an emergency could develop without the immediate knowledge of the air crew. One example centers around the APU. A power unit could malfunction and catch on fire outside of the pilot's view. In this case, the marshaller will make rapid figure-eight motions with their left arm while pointing toward the fire with the right.

Overheating brakes are also a potential cause for concern. The C-5M Super Galaxy has a maximum takeoff weight of approximately 840,000 pounds. Five sets of landing gear and 28 wheels bring all that bulk to a stop while landing, creating an enormous amount of heat. While not all aircraft have such drastic statistics, overheated brakes can create a hazard on any plane.

A marshaller can indicate that both sides of the aircraft's brakes are overheating by holding the elbows out at shoulder level and pointing to the ground with the wands. If only one side is overheated, the marshaller keeps one wand down and points to the wrist of that arm with the other wand. This should correlate to which side's brakes are hot from the pilot's point of view.

Should the worst happen and the air crew must evacuate the aircraft, a marshaller will first give the cut engine signal. Then, they will hold the wands at waist level and pull them rapidly over the shoulders, pantomiming the removal of seat belts and shoulder harnesses. If you see this on your commercial flight, you might want to start remembering the evacuation procedures you ignored at the beginning.

Chocks, landing gear pins, and brakes applied

Securing the aircraft on the ground is one of the final processes when landing or moving it. Several auxiliary procedures help ensure that an airplane will not shift or move, especially when personnel are on or near it.

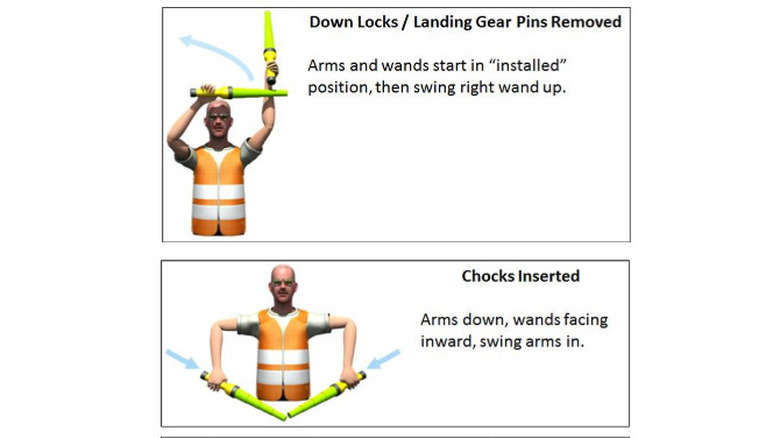

The first defense against unwanted movement is to apply the brakes. Marshallers indicate they want the pilot to place the brakes on by crossing the wands overhead and uncrossing them. Taking the brakes off means a marshaller must recross the wands.

Chocks are another part of ensuring an aircraft doesn't roll, especially if it has damaged its brakes with overheating upon landing. The ground crew will place chocks beneath the wheels to secure the craft further. The marshaller communicates that the chocks are in place by touching the tips of the wands together in front of their waist. Chocks removed is the opposite, with the marshaller pointing outward at waist level and pulling the wand handles apart.

Once an aircraft is settled on its landing gear, the ground crew will also insert special equipment known as landing gear pins into the landing apparatus. These pins are a backup that ensures the landing gear will not collapse or lower unexpectedly, keeping any personnel beneath the aircraft safe. A marshaller lets the pilot know the pins are installed by holding their left arm up and touching the wrist of that arm with the right hand. The right arm is swept vertically to indicate that the pins have been removed.

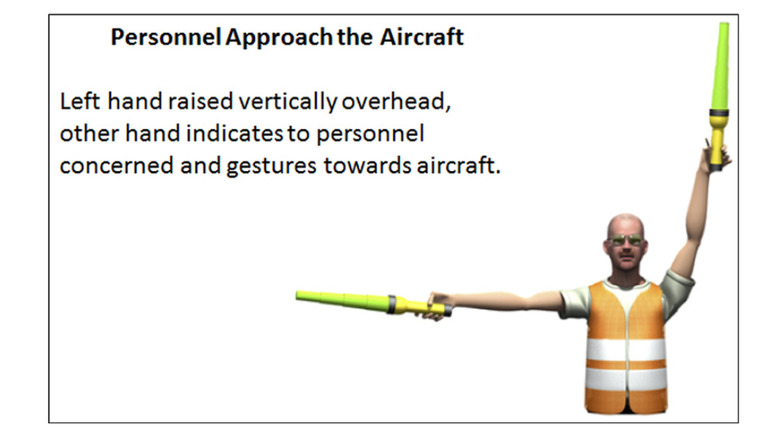

Personnel approach the aircraft

Aviation itself is dangerous, and approaching an aircraft on the ground, especially when its engines are running, can be fatal. In 2024, a person died after being sucked into a running aircraft engine at Amsterdam's Schipol International Airport. As recently as January 2025, a 17-year veteran of the Taiwanese military was killed when sucked into a jet engine during a routine inspection. These tragic incidents serve as a stark reminder of the perils of being around a running aircraft. It's crucial to always be cautious and alert in such situations.

When the aircraft has landed and finished moving along the marshalling chain to its final destination, shut down its engines and has been properly chocked, it is finally ready for personnel to approach safely. A pilot can request personnel approach by holding their hand up and drawing it toward their eyes. If it is safe and appropriate, the marshaller will indicate so by raising the left hand vertically overhead, pointing toward the personnel in question, and gesturing toward the plane.