10 Of The Most Notorious Weapons Used In WWII, And How They Worked

The technology of war is ever-changing. With each new conflict in history, scientists and engineers scramble to develop new ways to defeat the enemy. They have to, since the other side is doing the exact same thing — and these struggles can yield unintended civilian benefits, such as the acceleration of computer technology.

World War II was the defining historical moment of the 20th century. The war changed the world forever, and its repercussions are still felt, even to this day. With a final death toll in the range of 75 million people, it was the bloodiest conflict ever recorded in human history. The Allied powers ultimately won out against the Axis forces of Nazi Germany, Imperial Japan, and fascist Italy, but at great cost.

The weapons used in World War II demonstrated a notable advancement over those used in previous conflicts. Some were so destructive that they should never be used again. Here are 10 of the most notorious weapons used in WWII and how they worked.

M1 Garand

The M1 Garand, introduced in 1936, is one of the most iconic weapons in the history of the American warfighter. This rifle replaced the M1903 Springfield as the standard rifle of the U.S. military, and it was a huge improvement, eschewing slow bolt-action fire for a semi-automatic system, allowing for a faster fire rate. Likewise, the Garand featured an eight-round ammo capacity, greater than the Springfield's five-round stripper clips. The M1 Garand, with its semi-automatic fire, was superior to the bolt-action counterparts used by the Axis forces. General George Patton, a man who never minced words, called the M1, "The greatest battle implement ever devised."

Perhaps the most recognizable aspect of the M1 Garand was the distinct "ping" sound it made when an empty clip was ejected from the magazine, which would occur automatically when the all eight rounds were fired, allowing for quick reloading. Though the clip could be ejected manually, it was a tricky process that required both hands, pushing a button to unlatch the clip and operating the action to eject it. As a result, most soldiers simply fired off the remainder of any half-empty clips in order to go into the next encounter with a full set of eight bullets.

Browning Automatic Rifle

The name "Browning" is synonymous with American firearms, and for good reason. John Browning designed some of the most legendary weapons of all time, including the Auto-5 shotgun, the M1919 machine gun, the Winchester 1887, and the M1911 (more on that later). The B.A.R., or Browning Automatic Rifle, was an attempt to make a relatively lightweight weapon that could shoot .30-06 rifle rounds with a rapid rate of fire. Ultimately, the B.A.R. was a bit too heavy for its own good, weighing in at over 21 pounds unloaded, but it was still an intimidating weapon. In full-auto mode, the rifle could expend its 20-round magazine in seconds, though there was also a semi-automatic option on its fire selector, for more precise shooting.

The weapon featured a bipod for more stable aiming, though it was often discarded, since the bipod was a relic of its WWI trench warfare origins. Riflemen on the move would have little use for a bipod, and would often fire the weapon from the hip. While designed to shoot from the shoulder for maximum accuracy, it was a bit too cumbersome to try and do so while under enemy fire. However, what it lacked in dexterity, the B.A.R. more than made up for with firepower and sheer intimidation factor.

M2 Flamethrower

Flamethrower technology advanced considerably during World War II. When America first entered the war, they used the M1, which was eventually replaced by the M1A1, which itself was ultimately succeeded by the M2 flamethrower. Initially, flamethrowers used a mixture of oil and gasoline as fuel, but as the war progressed, this concoction was replaced with a new invention: Napalm. This thicker solution burned hotter and longer than gasoline and could shoot in a more concentrated stream, allowing flames to travel further, faster, and even deflect off walls.

An M2 flamethrower could spit flames for around ten seconds before running out of fuel, but those precious few seconds were more than enough to burn through a fortified bunker, killing or otherwise smoking out anyone hiding inside. Many movies and video games depict the fuel tank as prone to exploding upon being shot, but that's largely a myth for the sake of Hollywood-style action. In real life, it would take an incendiary bullet (non-existent for small arms of the era) to have a chance of exploding a flamethrower's fuel tank.

M3 Submachine Gun

The Thompson submachine gun (or Tommy Gun) gets all the glory, but the M3 was just as impactful on the battlefields of WWII. Nicknamed the "Grease Gun" because of its resemblance to a mechanic's tool for applying grease to cars, the M3 was chambered for .45 caliber cartridges, and held 30 rounds in a single magazine, though one of the weapon's strengths was the ability to easily convert it to support 9 mm ammunition. It was much more stable and accurate than the Thompson, which is what the M3 was designed to replace. It was also much cheaper to produce than the Thompson, which presumably made it a favorite among military accountants.

The M3 was an early favorite of clandestine special forces groups like the OSS, who commissioned a version of the weapon with an integrated sound suppressor. Overall, the Grease Gun might not look as flashy or sturdy as the Thompson, but looks can be deceiving. The M3 was compact, powerful, and versatile, allowing Allied soldiers to survive during close-quarters encounters.

Nambu Type 99

They may have had rocket-powered kamikaze planes and secret jet fighters, but the Japanese army was somewhat underequipped during WWII. Their Arisaka bolt-action rifle, for instance, could not keep up with the Army's M1 Garand. Likewise, while the Nambu Type 100 submachine gun was seen as an effective weapon, it had a limited production run and was thus rarely seen in the Pacific Theater... or anywhere, for that matter. Nevertheless, the Japanese army made up for their comparatively limited arsenal with troop numbers, tactical prowess, and an unerring devotion to the Empire.

When it came to heavier weapons, the Imperial army had an ace up their sleeve in the form of the Nambu Type 99 LMG. Recognizable due to its unconventional magazine placement — sticking out of the top of the weapon, rather than the bottom — the Type 99 fired Japan's new ammunition, the 7.7x58 mm cartridge, though it could also shoot the same ammo as their standard Arisaka rifles, the 6.5x50 mm cartridge. It weighed 22 pounds unloaded, and enabled the Japanese to defensively hold onto territory the Allies were trying to claim, stretching the island-hopping campaign in the Pacific into a grueling tug-of-war. As a testament to its utility, the Type 99 would be used by Communist forces in the Korean War and the Vietnam War.

Welrod

This curious-looking Welrod pistol was designed by British inventor Major Hugh Reeves, who helped invent various stealth technologies, including glowing nighttime sights, the integrated silencer for the Sten submachine gun, and the "sleeve gun," a single shot weapon that could be hidden against an agent's wrist and deployed for a stealth takedown. Likewise, the Welrod was a stealth gun, a pistol with an integrated silencer that could fire either 9x19mm Parabellum rounds with a six-shot magazine or .32 ACP ammunition with an eight-round capacity.

Though it could be used at ranges of up to 30 yards, the weapon was primarily designed for up close and personal assassination. The Welrod was quiet, even compared to other silenced weapons, but when pressed directly against a target, it was virtually silent, even to the person firing the gun. It's no wonder, then, that the Welrod was a favorite of spies and other covert operatives of the era, though official records regarding its use are, by their nature, hard to come by.

S-mine

Today, the term "Bouncing Betty" refers to any land mine that pops up into the air before detonating, but the German-developed S-mine was the first. Like its nickname suggests, the S-mine is notable for maximizing its destructive output by jumping before exploding. This is the result of a secondary charge, attached to a spring. In normal use, the mine would be buried under loose dirt, with just the three prongs on top barely sticking out from the ground, almost imperceptible. When the mine was activated, either by tripwire or by stepping on it, the secondary charge would detonate, sending the mine shooting up, three or so feet into the air, before the primary detonation initiated, surely killing or maiming whoever was in the vicinity.

The S-mine was effective as both an anti-personnel device and a psychologically intimidating weapon. Allied forces in a field of S-mines would be forced to slow their advance and meticulously dig around for mines before every step. The design was so effective that numerous other countries made their own Bouncing Betty variants, including the United States, which created the M2 and M16 mines.

MG 42

Nazi Germany's arsenal of weapons was formidable, but perhaps no weapon in their roster was as downright intimidating as the MG 42. The weapon boasted a fire rate of 1200 rounds per minute, giving it a distinct sound profile that earned the MG 42 the infamous nickname, "Hitler's Buzzsaw." The weapon weighed 25 pounds, which is considerable, but not bad for a light machine gun, especially compared to its Allied counterpart, the Browning M1919, which weighed 31 pounds, and was much bigger and more unwieldy when carried around.

Another advantage of the MG 42 was its solution to overheating. When the barrel got too hot for the weapon to use reliably, it could be simply removed and replaced with a new one. On the MG 42, this took a matter of seconds, while it was a long and arduous process on the Browning M1919, though that weapon took much longer to overheat, thanks to its sturdier build and lower rate of fire. In any case, Allied troops who came up against this weapon and survived surely had a harrowing story to tell afterwards.

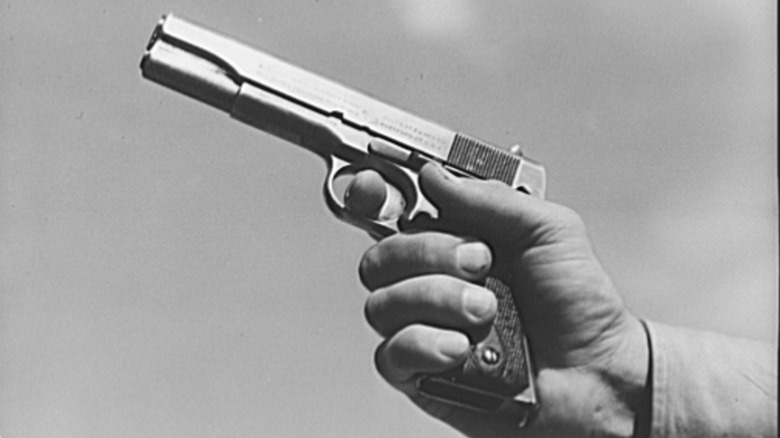

Colt M1911

Perhaps the most iconic sidearm of all, the Colt M1911 was first adopted by the US Army in 1911, hence the name, and variants are still in use to this day. The M1911 held seven rounds in a magazine, with room for one more in the chamber. By WWII, the design had evolved into the M1911A1, though the changes were mostly superficial, like minor adjustments to the sights, a shorter trigger, and adjustments to the grip texture. The biggest change was a lengthened safety spur, a move intended to reduce "hammer bite," which is when the hammer tears at the skin between the thumb and forefinger.

The weapon was heavy, and the powerful .45 round caused significant recoil, but those were acceptable trade-offs for American soldiers who needed to not only take down an enemy soldier, but stop them dead in their tracks. This was particularly important in the Pacific Theater of the war, where the Japanese army frequently charged at American forces with bayonets and swords.

The M1911 served as the standard sidearm for the U.S. military from 1911 through to 1985, a 74-year reign. It was ultimately replaced by the Beretta M9, which offered a higher-capacity "double stack" magazine, but reduced impact thanks to its 9 mm cartridge. Add in the heavier, thirteen-pound trigger pull (compared to the M1911's six-pound pull), and the result was a gun that, while effective and accurate, lacked the character, stopping power, and old-school prestige of the M1911. While WWII was defined in part by new technologies, sometimes the classics won out.

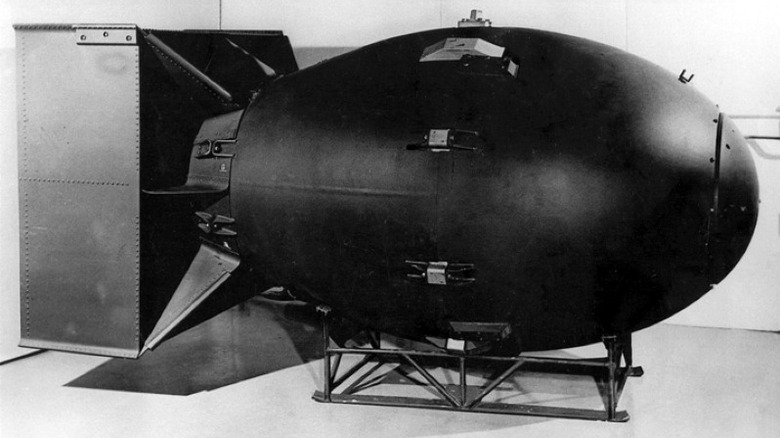

The atomic bomb

To this day, historians debate whether it was strategically necessary for the United States to drop two atomic bombs on Japan. Some say the war would have been prolonged without the attacks, while others insist the war was already ending, and that the atomic strikes were a needless show of force to usher in a new age of American military superiority. The one thing everyone can agree on is that the world changed forever on August 6 and August 9, 1945.

In 1942, work began in earnest on the Manhattan Project, America's nuclear weapons program. Imperial Japan and Nazi Germany had similar projects, but they never advanced far enough to produce a viable weapon. On August 6, 1945, the Enola Gay, piloted by Colonel Paul Tibbets, dropped a bomb, called Little Boy, on the city of Hiroshima. Three days later, the Bockscar, piloted by Major Charles Sweeney, dropped the Fat Man bomb on Nagasaki. Together, the attacks killed over 200,000 people, most of whom were civilians. On August 15, Emperor Hirohito surrendered to the Allies, ending World War II.

In the decades since, America and other countries have expanded their nuclear weapons programs, creating intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) armed with nuclear warheads that possess many times the destructive power of the bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Today, there are roughly 13,000 nuclear weapons worldwide.