The World's First Minivan And The Man Who Built It

The minivan not only saved Chrysler from driving off a cliff into bankruptcy, but it also changed the automotive world as we know it. Both the Dodge Caravan and Plymouth Voyager rolled off Chrysler's Windsor, Canada, assembly line at the end of 1983 (for the 1984 model year), and ushered in the start of the modern minivan market. The funny thing about those "original" minivans, though, is that they weren't the first.

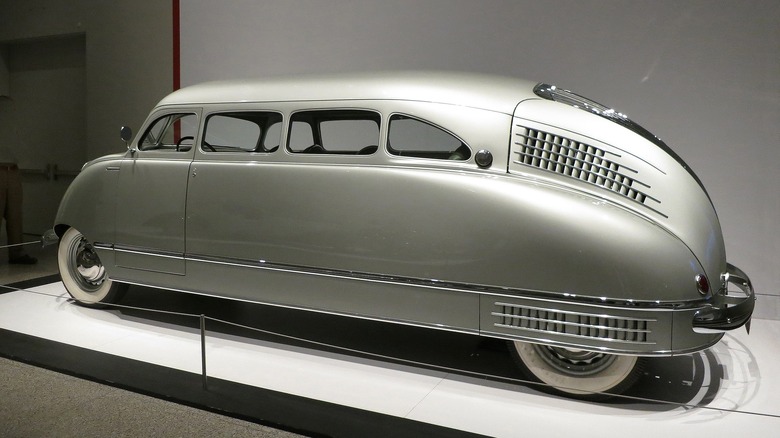

That honor belongs to an aerodynamic piece of four-wheeled Art Deco that began riding the highways and byways of our country in 1934 — a full half-century before those other guys. It wasn't just that it had a bold globular, curvilinear form that also happened to reshape the automotive landscape of its time — but that it was designed by a man who, in his own right, was as colorful and exciting as the miniature people mover he named after an Egyptian bug.

The Scarab was William Bushnell Stout's attempt to "Simplicate and add more lightness," a motto he adhered to during his design processes. To understand the Scarab, one must first know the man who built it. He was a dynamic, inventive man with many talents — whose distant relative, David Bushnell, created one of the world's first submersibles (the "Bushnell Turtle") used during the American Revolution.

During his career, Stout was the chief engineer at Schurmeir Motor Truck Company and Scripps-Booth Automobile Company. When the Packard Motor Car Company poached him, he wasn't tasked with designing automobiles ... but airplanes.

[Featured image by Jim Evans via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | CC BY-SA 4.0]

Stout envisioned much friendlier skies

Stout's love affair with flight led him to believe that an airplane constructed entirely of metal was a better overall design (not to mention sturdier) than the tried-and-true choice of simply stretching fabric over a wood frame. But the aeronautical industry's lack of forward-thinking didn't stop him.

In the early 1920s, Stout came up with an innovative design using cantilevered, internally braced wings to build the "Batwing," which became the first commercial monoplane in the United States. With Henry Ford as a primary investor (along with 19 others), Stout formed his own airplane-building company in 1922 — the Stout Metal Airplane Company.

In 1924, he built the Tri-Motor: the first all-metal high-wing monoplane with three engines and fixed landing gear. Ford saw the plane's promise and bought out Stout in 1925, renaming it the Ford Airplane Company. Meanwhile, Stout continued using the Tri-Motors to power his newly-formed Stout Air Service, the first regularly scheduled passenger airline in America, which later became United Airlines. One Tri-Motor from 1929 is still worth a ton of money today.

Long before the Hanna-Barbara animation studio dreamed up George Jetson's flying car, Stout believed flying should be as normal for the average American as drinking a cup of coffee. In 1931, he built the first of two versions of what he called the "Sky Car." While the first iteration wasn't built specifically for the road, the second was.

When Stout wasn't building and inventing, he even managed to serve as the auto and airplane editor at the Chicago Tribune for a time.

[Featured image by Texanpilot1 via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | CC BY-SA 4.0]

Enter the Scarab

Thus, it should be no surprise that Stout is now regarded as the "father of modern aviation." Since the aviation industry wasn't all that receptive to his innovations, he took what he'd learned and focused his attention on creating an entirely new kind of automobile instead.

The Stout Scarab is considered one of the rarest vehicles on the planet because only a few were made between 1934 and 1939. Some claim Stout Engineering Laboratories made as many as nine, while others say at least six came to fruition. Alas, only five are still known to exist.

Each one was built by hand, so no two were alike. It came with an outrageous cost of $5,000 for that uniqueness, which is about $116,000 in today's dollars. In the 1934 Great Depression era, this was an unattainable pipe dream for most. Then again, Stout intentionally meant to keep production low at 100 per year, with sales by invitation only. The ownership list read like the stock market, and included Willard Dow (of Dow Chemical), William K. Wrigley (of chewing gum fame), Harvey Firestone (tires), and Robert Stranahan (Champion Spark Plugs).

Stout's entire marketing plan rested on appealing to the wealthy first, many of whom were on his company's board, then to a broader audience. In a 1935 issue of Scientific American, Stout said he wanted to give the driver "infinitely better vision from all angles" while providing a lighter, safer, spacious, more efficient vehicle "without sacrificing maneuverability."

Drive like an Egyptian

In the 1930s, Art Deco and Egyptian themes were all the rage. The term "Art Deco" refers to a design style that originated in France in the mid-1920s. It used geometric shapes, clean lines, and stylized forms (like chevrons and zigzags) to create a "streamlined" look used in art, fashion, architecture, and other designs, all of which symbolized wealth and sophistication.

The Scarab was named after the sacred Egyptian dung beetle and represents rebirth, resurrection, and renewal. With its bulbous, puffy appearance, the vehicle looked very much like a beetle. Some said it looked like a turtle's shell, which is ironic given that the submersible Stout's ancestor had created centuries before was said to look like "two upper tortoise shells of equal size, joined together." It looked a whole lot better than Plymouth's minivan concept, the Voyager III.

Stout's 1932 prototype had aluminum skin fitted to an aluminum space frame, similar to an airplane's. The aluminum was later swapped with steel because it was too costly. The body panels were sculpted to be as streamlined as possible. The fenders were incorporated into the body, skirts were fitted over the rear wheels, and it lacked running boards — a standard on most cars at the time.

Four windows lined each side, with the glass installed flush to minimize cabin noise and reduce drag. This "minivan" had only two doors: A slender driver's side door, and a second, larger door placed mid-cabin on the right for passengers. Additionally, their hinges were hidden, and handles were removed, instead opting to use a push button that electronically released the door latch.

[Featured image by Michael Barera via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | CC BY-SA 4.0]

Chrome for days

The front of the Scarab, in many ways, resembled a "face." Split double windshields sat above two oversized headlights wrapped and shrouded by chrome and thin bars. Between them was a hard-to-miss, highly stylized Egyptian scarab that looked like a nose and mustache.

More stylized chrome bars swept down across the rear of the vehicle in a cascading waterfall effect that concealed the rear windshield and acted like cooling grills for the rear-mounted engine. On each side of the car sat separate trunks with separate lids, which when opened, made the Scarab appear to have wings (much like the bug it was named after). It may not have been one of the most beautiful pre-war cars ever built, but it sure caught the eye.

Instead of a separate chassis and body, Stout's innovative approach used a unitized body structure (aka unibody), where all the major elements of the vehicle were welded together into one rigid structure. This provided better handling, more interior space, and lighter curb weight. Even with steel components, the Scarab only weighed 3,300 pounds.

As mentioned, the vehicle had a rear-mounted engine and, thanks to his previous associations with Henry Ford, used a Ford-built flathead V8 that produced 95 horsepower and 154 pound-feet of torque. It sat on top of the rear axle, with the flywheel and clutch facing forward, which gave it better traction and the added bonus of more cabin space. The three-speed manual transmission (built by Stout) sat ahead of the engine and improved acceleration. Given that the bloated Scarab was 195.5 inches (over 16 feet) long, the reported 0-60 mph in 15 seconds was impressive.

[Featured image by Michael Barera via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | CC BY-SA 4.0]

Stout's Scarab could never get off the ground

Inside was an array of features that few vehicles could claim: ambient lighting, thermostat-controlled heating, a dust filter that scrubbed out pollen, leather seats, a folding table, and power door locks. The dashboard, doors, and lower seat frames were all cast magnesium. The rear bench seat could be slept on, and the two passenger seats moved anywhere because they weren't attached to the floor. The roof liner was made from wicker and had a woven basket appearance.

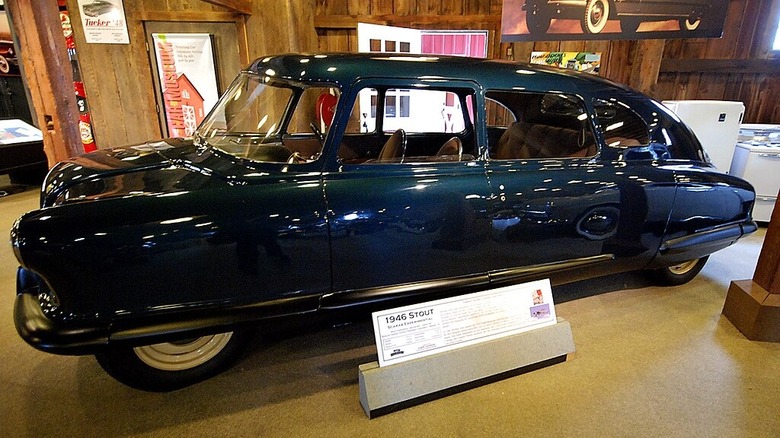

As The Great Depression wore on, sales stopped, and the vehicle fell to the wayside. On the heels of that economic disaster, World War II sprang up in Europe, causing many (including Stout) to cease regular business functions. After the war, Stout resurrected the idea as the Stout Scarab Experimental (aka Stout Project Y).

This iteration looked far more like a conventional sedan, but in more firsts, had a fiberglass body and a fully pneumatic suspension. Alas, that project never went into production either. However, given that Stout wanted his renewed attempt to have an even higher MSRP of $10,000, chances are it wouldn't have sold well either.

It would take some four more decades before the American public was ready for a proper minivan. Many of the features found in the Dodge Caravan and Plymouth Voyager — flex seating, big side passenger door, spacious interior created by the lack of a driveshaft tunnel — can be attributed to the Stout Scarab and the man who built it.

[Featured image by Joanna Poe via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | CC BY-SA 2.0]