Graf Zeppelin: Germany's Unfinished Aircraft Carrier Of WWII

Many people believe Nazis had some of the most advanced technology of World War II. The Messerschmitt Me-163 Komet was probably the fastest plane in the skies back then, even if it was neither safe nor fuel efficient, and Nazis also planned to bomb New York City using a plane that doubled as a space shuttle. The latter idea might explain why, after the war, the U.S. recruited many ex-Nazi scientists to work in more beneficial fields via Operation Paperclip. But for every technological marvel Nazis produced, at least five of their mechanical machinations failed.

World War II historians recognize how Nazis devastated shipping lanes with U-boats (aka. submarines) and steamrolled fortified positions with blitzkrieg maneuvers. However, Nazi military tactics had one glaring hole: Nazis never fielded aircraft carriers. Most people know how effective these floating runways were during numerous campaigns — the infamous attack on Pearl Harbor was carried out by the Japanese aircraft carriers Akagi, Kaga, Sōryū, Hiryū, Shōkaku, and Zuikaku.

While other Axis powers frequently used carriers, the Nazis never did, but not for lack of trying. Before World War II even started, Adolf Hitler approved of a plan to manufacture several carriers, starting with the Graf Zeppelin. But, quite ironically, the Nazi war efforts (and the age-old Nazi tradition of stabbing everyone in the back) torpedoed the Graf Zeppelin and all subsequent Nazi aircraft carriers.

What was the Graf Zeppelin?

In 1928, Luftschiffbau Zeppelin launched the LZ 127 Graf Zeppelin. This passenger blimp flew until 1937 and was the world's first commercial transatlantic passenger airship. The LZ 127 Graf Zeppelin was not the Graf Zeppelin Hitler approved to deploy fighters and bombers over battlefields, but since it's the first result that comes up in Google searches, we had to make the distinction.

For the purposes of this article, the "actual" Graf Zeppelin was a class of ship originally drafted by Grand Admiral Erich Raeder in the mid-to-late 1930s. He and his team wanted to produce a ship that could help future German fleets compete with the vessels and tactics of rival countries. To this end, Raeder took inspiration from foreign carriers, including the Japanese Akagi. After completing his research, Raeder drew up "Plan Z," a proposition to construct a total of four aircraft carriers. The first of these ships was dubbed "Flugzeugträger A," which translated to "Aircraft Carrier A" or just "Carrier A." Hitler eventually christened the ship the Graf Zeppelin, after the founder of the Zeppelin, Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin — "Graf" means "Count" in German.

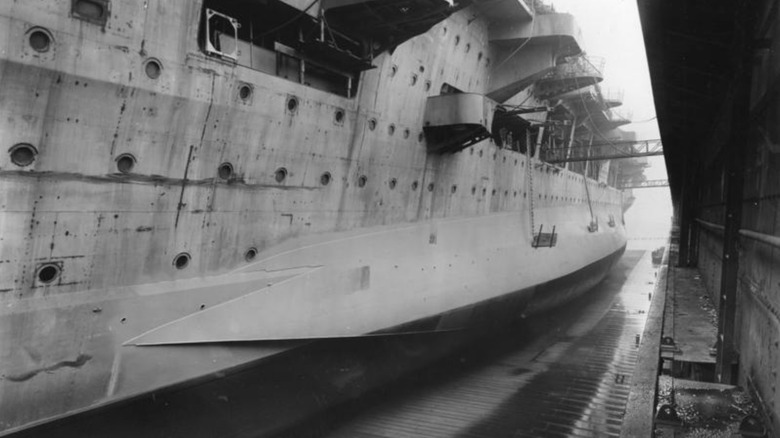

Since the Graf Zeppelin was Germany's first aircraft carrier, its engineers and architects predictably ran into many problems. For instance, the ship was weighed down with more artillery batteries than contemporary aircraft carriers, and engineers had to scale back plans, such as how many planes the Graf Zeppelin would hold. The second Graf Zeppelin-class ship, Flugzeugträger B, was pushed back so its engineers could learn from the first Graf Zeppelin's mistakes. But the second carrier was eventually dismantled shortly after construction started. As for the other two proposed vessels, they were canceled before they even received codenames.

A crash course on the Graf Zeppelin construction

Recycling was a huge part of the war effort during World War II. Why smelt new metal parts when you can just melt down donated kitchen pans and use those to build the parts? Why construct new aircraft carriers when you can convert existing ships to serve a new purpose? Germany was one of the few, if only, countries to try and build an aircraft carrier from scratch, which was a huge undertaking given its size.

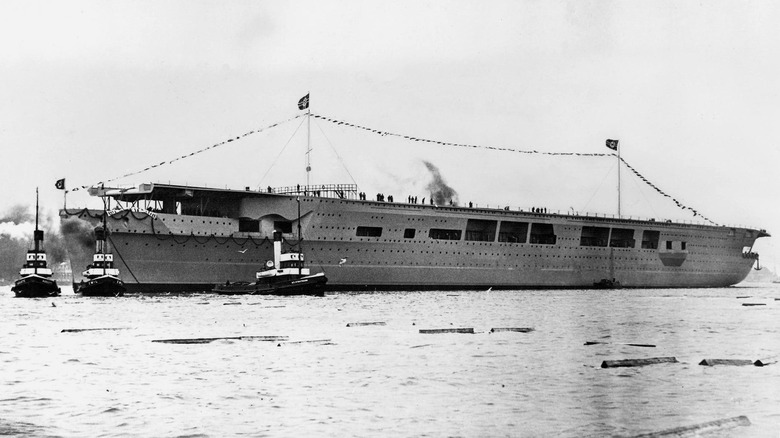

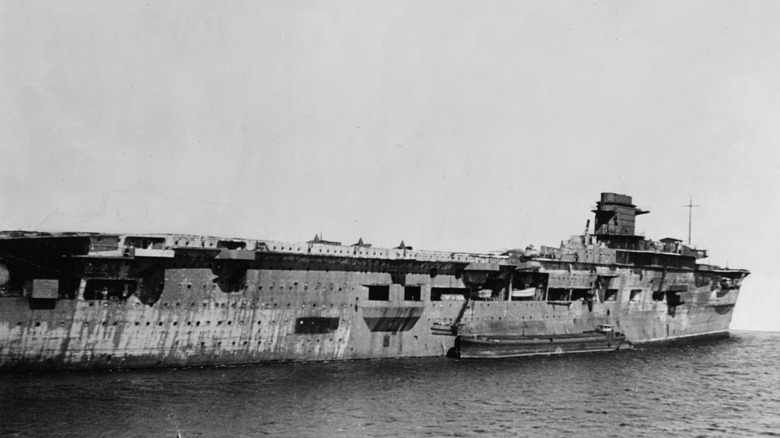

Construction of the Graf Zeppelin officially started on December 28, 1936, in a shipyard in Kiel, Germany. However, workers had to wait until the battleship Gneisenau was complete, as it took up dock space. When the Graf Zeppelin launched on December 8, 1938, the vessel's flight deck stretched 790 feet, but there seems to be some disagreement on those numbers, as some historians think the flight deck was 709 feet long. Whatever the ship's true length, many officials agree the Graf Zeppelin boasted a 200,000 horsepower reactor that gave it a range of 6,000 nautical miles, a max speed of around 35 knots (which Hitler thought was too slow), and a complement of around 1,760 officers.

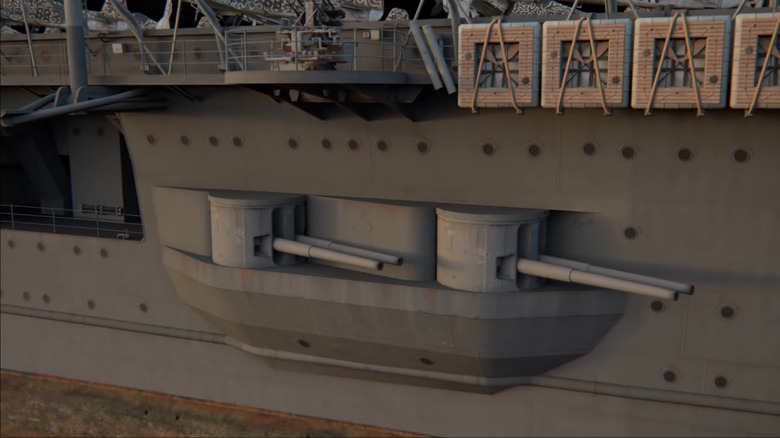

When it came to armaments, the Graf Zeppelin sported weapons such as 22 37mm anti-aircraft guns. However, the ship was designed primarily to rely on its airplanes. The carrier had enough storage space for up to 42 planes, which would have consisted of 12 modified Junkers Ju-87 "Stuka" bombers, 10 Messerschmitt BF-109T fighters, and 20 Fieseler Fi-162 torpedo bombers, all launched via catapult. However, some historians claim the Graf Zeppelin would have carried 13 Ju-87 bombers.

[Featured image by U.S. Navy National Museum of Naval Aviation via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | Public Domain]

Long story short: World War II killed the Graf Zeppelin

Nazis had problems with leadership. Not only did different military branch leaders scheme against each other, but they all answered directly to a führer who, by some accounts, was quite possibly schizophrenic. This dysfunctional leadership doomed many projects, including the Graf Zeppelin, but few hurt the ship's potential more than its own architect.

While the Graf Zeppelin launched in 1938, it was only 85% complete at the time. Work stalled afterward due to a shortage of builders and materials caused by the start of World War II. Shipyards had to focus on U-boat construction, so all other projects were put on the back burner. However, the Graf Zeppelin's first true death knell occurred after Germany conquered Norway in 1940. To defend their newly occupied territory, Erich Raeder ordered the Kriegsmarine (Nazi Germany's navy) to strip the Graf Zeppelin of its 15cm guns and use them as shore batteries since the carrier wouldn't be ready before 1941.

For a time, the Graf Zeppelin seemed as if it was forgotten, but in April of 1942, Raeder asked Hitler to revive the project. Raeder had seen what British aircraft carriers had done to Bismarck and Tirpitz and the devastation Japanese carriers wrought on Pearl Harbor. Raeder convinced Hitler to resume construction on the Graf Zeppelin, but since its planned technology was outdated, Raeder demanded newer fighters, modernized catapults, and more advanced AA guns.

Not only did the head of the Luftwaffe (Nazi Germany's air force), Hermann Goring, refuse to construct new planes, but in January of 1943, Hitler, in one of his classic tantrums, replaced Raeder with the Kriegsmarine's Commander of Submarines, Karl Dӧnitz, and demanded all larger ships be scrapped. While the Graf Zeppelin avoided this fate, all major work was still canceled.

[Featured image by Royal Air Force via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | Public Domain]

Every which way but the battlefield

Like many Nazi ships, the Graf Zeppelin was meant less for harassing military targets and more for attacking civilian shipping convoys, especially British ones. To do that, the Graf Zeppelin would have to venture into oceanic waters, but the ship never left the confines of the Baltic Sea.

Since the Graf Zeppelin was only 85% complete when it "launched," it was in no position to fulfill its planned combat role. While engineers mounted temporary 3.7cm guns onto the ship, the Graf Zeppelin was still a huge target, so the carrier was towed to Gotenhafen, Poland, where Nazis used the vessel's sizable hangar as a glorified timber warehouse. Afterward, Nazis towed the Graf Zeppelin to Stettin, Poland, for safekeeping and later back to Kiel in 1942 so the ship could be completed. But that never happened.

Instead of workers finishing the construction of the Graf Zeppelin, they found that the ship actually got in the way of building submarines, so it had to go. Nazis enlisted a crew of civilians — as opposed to more qualified Kriegsmarine officers — to float the ship towards the Moenne tributary, where it languished away from anything resembling a battlefield. The Nazi Captain Hadeler floated the idea of using the Graf Zeppelin as a temporary barracks, but that proposal never surfaced.

Eventually, the Graf Zeppelin met its end when it was once again docked in Stettin. With Russian forces closing in, then-commander of the Kriegsmarine, Karl Dӧnitz, ordered the ship scuttled and sunk into the waters. In a moment of hindsight humor, since Winston Churchill had little intel on the Graf Zeppelin, he thought that all its moving around meant the ship was a huge threat to British interests.

[Featured image by Bundesarchiv, RM 25 Bild-64 via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | CC-BY-SA 3.0]

Always altering armaments

Erich Raeder had high hopes for the Graf Zeppelin. He originally wanted the carrier to house anywhere between 50 to 60 reconnaissance planes and boast a complement of eight 8-inch guns. Eventually, reality caught up to Raeder, and he had to change his plans.

As previously stated, Raeder's final blueprint for the Graf Zeppelin called for enough space to house 42 or 43 planes, which would consist of Messerschmitt ME-109T fighters, Junkers Ju-87 bombers, and Fieseler Fi-167 planes. However, many of these planes had to be adapted for use on the Graf Zeppelin, and the Kriegsmarine considered these changes "inadequate."

Moreover, in 1937/38, the carrier's role switched from reconnaissance to all-out offense, and plans dropped the Fieselers in favor of 30 Messerschmitts and 12 Junkers in total. However, some historians claim the Graf Zeppelin would have housed 33 planes, consisting of 10 Messerschmits and 23 Junkers. Of course, the vessel's actual bomber-to-fighter ratio is moot since construction was paused until 1942.

By the time work resumed on the Graf Zeppelin, much of its loadout was horribly out of date. Raedler demanded a new plane specifically designed to be launched via carrier catapult, the Messerschmitt ME-155, but when the Graf Zeppelin project was shelved, so were its ME-155s. Moreover, Hitler approved of several improvements, including stronger catapults, better radios, and more guns. To increase the ship's cruising radius and to keep it afloat with all this new weight, the Graf Zeppelin would have been outfitted with oil-filled blisters. However, thanks to these new additions, the ship wouldn't have been ready until the winter of 1943/44. Thanks to Hitler's temper tantrum, it didn't even last until January of 1943.

In Soviet Russia, Graf Zeppelin eludes you

When the Graf Zeppelin was scuttled and sunk, the order was meant to keep the ship out of Soviet hands. Just one problem: The waters weren't deep enough. Soviet forces managed to raise the ship, but what they did with it is anyone's guess. At least until the Soviet Union fell.

Before historians gained access to Soviet records, they did a lot of guesswork. Clark Reynolds, for instance, believed a Russian salvage team floated the Graf Zeppelin towards Swinemünde, Poland, stuffed it with spoils of war such as sections of U-boat, and then started towing it towards Leningrad. However, the ship struck a mine north of Danzig and never made it. According to naval analyst Norman Polmar, however, Soviet records state the Graf Zeppelin was anchored somewhere off Swinemünde and used as target practice to test how to sink large aircraft carriers. Even though the ship never saw combat or completion, it proved surprisingly resilient and allegedly withstood six bomb explosions and two 21-inch torpedo strikes before finally sinking.

While records differ significantly, nobody ever found tangible evidence of the Graf Zeppelin's fate until 2006, when the Polish oil company Petrobaltic discovered an 820-foot wreckage north of Wladyslawowo, Poland. The sunken ship was found 264 feet below the surface, and naval experts used underwater drones to confirm that the wreckage was indeed the Graf Zeppelin. While the ship was relatively intact, a spokesperson for the Polish navy, Lieutenant Commander Bartosz Zajda, said, "Technically, it's impossible to pull it out of the water."

No aircraft carrier, no aircrafts for carriers

Since the Graf Zeppelin was an aircraft carrier, the Kriegsmarine and Luftwaffe held vested interests in the vessel because they were in charge of Nazi Germany's naval and aerial activities, respectively. But you know what they say about putting all your eggs in one basket, especially when those eggs refuse to cooperate.

Shortly after construction of the Graf Zeppelin started, the Luftwaffe started training personnel on how to use the carrier's flight deck. To this end, they set up a practice runway near Travemünde, Germany, done up to resemble that of the Graf Zeppelin. However, as soon as the Graf Zeppelin's guns were sent to Norway, the Luftwaffe ceased all carrier-oriented practice operations and assumed they had heard the last of the vessel.

To make matters worse for the Graf Zeppelin, the manufacturing wing of Nazi Germany was stretched thin. Not only did manufacturing plants prioritize U-boats over the Graf Zeppelin, but even after construction on the ship resumed in 1942, Hermann Goring claimed that manufacturing plants were overwhelmed and couldn't build the planes Erich Raeder wanted.

Goring suggested that existing fighters should be converted for the carrier. Meanwhile, Hitler believed if workers could convert existing ships into more aircraft carriers, airplane manufacturing shortages would disappear. Needless to say, none of these plans ever bore any fruit. The Kriegsmarine's and Luftwaffe's constant backstabbing probably didn't help matters.