The Forgotten Chevy Aerovette Concept That Was Ahead Of Its Time

Unlike the smooth, aerodynamic design of General Motors' concept Corvette known as the "Aerovette," the story of how it went from the drawing board to the auto show floor is most certainly not straight. The life and death of this particular prototype is a convoluted coalescence of people, parts, engines, and finally... just plain old (bad) timing.

While Harley Earl may be the true father of the Corvette, there is no mistaking that Zora Arkus-Duntov is the man who truly made it a legend. Starting in 1953, Arku-Duntov worked at Chevrolet for 22 years. He was Corvette's first chief engineer and served in that role from December 1967 until December 1974. During his tenure, he never stopped trying to make the 'Vette better, stronger, and faster — like Oscar Goldman did to Steve Austin, the Six Million Dollar Man. The Aerovette was one of those attempts.

By all accounts, it began its climb to historical (ir)relevance in the late 1960s as Experimental Project 882 (XP-822). Arkus-Duntov was keen on creating the first mid-engine Corvette but, for one reason or another, kept coming up short. The lineage of the XP-822 alone is confounding. Kenneth William Kayser, the author of several detailed books on the Corvette's history, says there were three in total, with the fourth renamed the Aerovette.

Enter the Wankel rotary engine

Oddly, the first XP-882 appeared in 1967 as a three-wheel vehicle complete with a turbine engine, a far cry from the final version of the finished vehicle we know today. The second XP-822 made a "made a surprise appearance" at the New York car show in 1970. The "surprise" was forced on Chevrolet when Ford announced it had purchased De Tomaso, the Italian sports car company. Ironically, General Manager John DeLorean (yes, of "Back to the Future" fame) had just a year earlier scrubbed the XP-882, decided the company needed a mid-engine sports car to compete and reinstated the project.

By the time the third XP-822 version rolled out in 1975, some body modifications were made, like removing the old swinging doors in favor of bi-fold gull-wing doors and a longer, more tapered body slant from tip to tail. It also included a drastic change to the engine. Instead of a typical Chevy V-8, Arkus-Duntov and his team dropped in 6.2-liter twin-rotor Wankel engines (with four rotors/chambers) capable of producing some 420bhp.

The engine swap was done for two reasons. First, Ed Cole, president of GM then, was "fascinated by the smoothness and power of the Wankel rotary engine." Secondly, Arkus-Duntov believed the Wankel-powered car was faster from zero to 100mph than a big block 7.4-litre V8 454 found in the high-end C3 Corvette (via Top Gear).

Global events killed the concept Corvette

But lousy timing would intervene. First, the Clean Air Act was passed in 1970, which, for the first time, gave federal and state governments the power to limit emissions from not only industrial buildings and other sources, but, more importantly... automobiles. Then, in 1973, the OPEC (Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries) oil crisis quickly put a kibosh on gas-guzzling vehicles. This global catastrophe amounted to a knockout uppercut from Steve Austin, which has rippled through the decades. One glaring example of the auto industry's backs could be seen with Cadillac's 8.2-liter V8, which, in 1970, kicked out 400bhp. By 1976 it had dwindled to a gutted, wheezing 190bhp (via Top Gear).

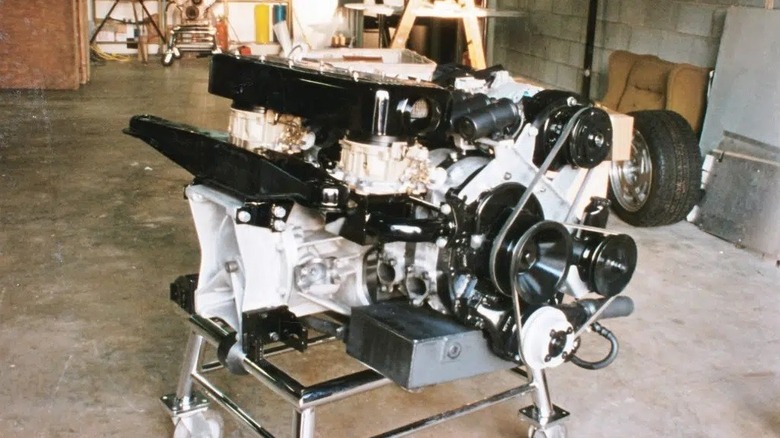

Despite providing a ton of power in a small, lightweight package, rotary engines were notorious for using tons of oil and gas. So, another course correction was made. Chevy pulled out the Wankel engines and dropped in a 400-cubic-inch (6.6-liter) transverse V-8. This fourth version of the XP-882 made the rounds at various car shows, earning public and critical acclaim.

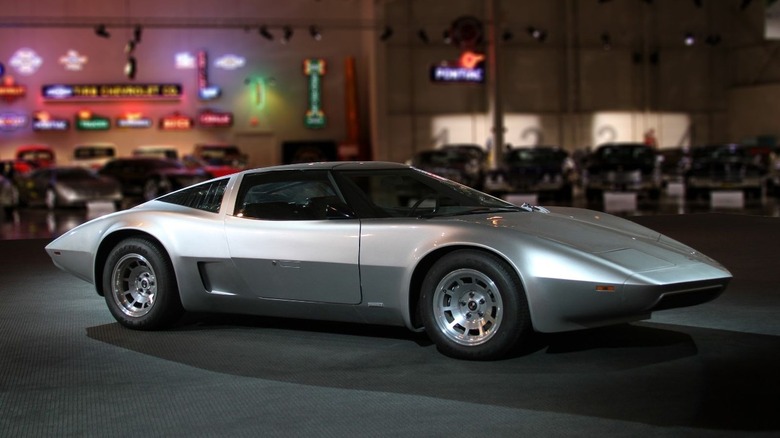

The two-seat Aerovette had a deep "V" wrap-around windshield slopped at 72 degrees that hid the front pillars. Its bi-fold gull-wing doors gave the body, which was vaguely reminiscent of the conventional Corvette, an Italian flair. The door's fixed windows were part of the fiberglass body, with a steel and aluminum tubular frame.

With the placement of the engine mid-ship, glass louvers were placed on the quarter panels to allow heat from the engine compartment to escape. Slits along the body's exterior, just in front of the rear wheels, allowed air to get to the carburetors while the radiator and air conditioning sat near the front of the car (via Vette Vues).

Knight riding back to the future

Even with K.I.T.T. (Knight Industries Two Thousand) not making its first appearance on "Knight Rider" for a few more years, the interior of the Aerovette we every bit as futuristic. The dashboard was replete with a dizzying array of flashing lights and digital digits that displayed speed, fuel supply, water temp, oil pressure, voltage, time, date, and radio station frequency. A "linear light emitting diode system" served as a tachometer, with the green lights signaling that the car was still under the 5,000 RPM threshold. When it approached 7,000, the lights turned red (via Vette Vues).

The car's "master warning system" was powered by an onboard computer that would tell the driver if the door wasn't closed or the seatbelt wasn't clicked. While the seats were fixed and could only move up and down, just about everything else could be adjusted, including the steering wheel and pedals. One interesting safety feature was the "energy absorbing bumpers" on both ends of the car that, in theory, shielded it from impacts... as long as the car wasn't going more than ten miles per hour(via Vette Vues).

The Aerovette was given the green light in 1980 but never made it into production. After Arkus-Duntov retired at the end of 1974, his replacement wanted to stick with the Corvette's traditional front-engine placement. Plus, it was simply too expensive to produce. The final XP-822 Aerovette (and some of its predecessors) can be seen in General Motors' Heritage Collection in Sterling Heights, Michigan.