I Was Wrong About Project Ara

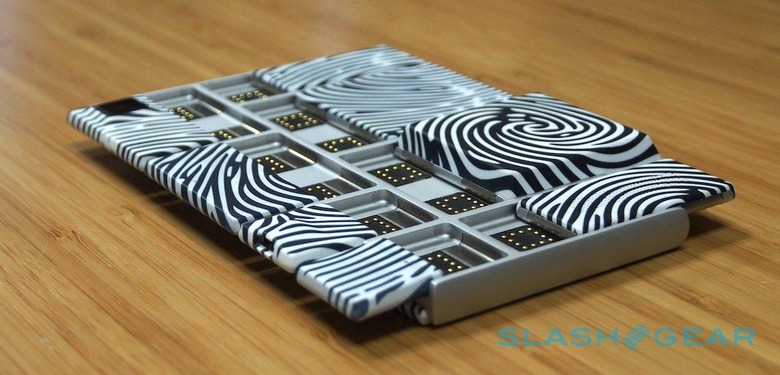

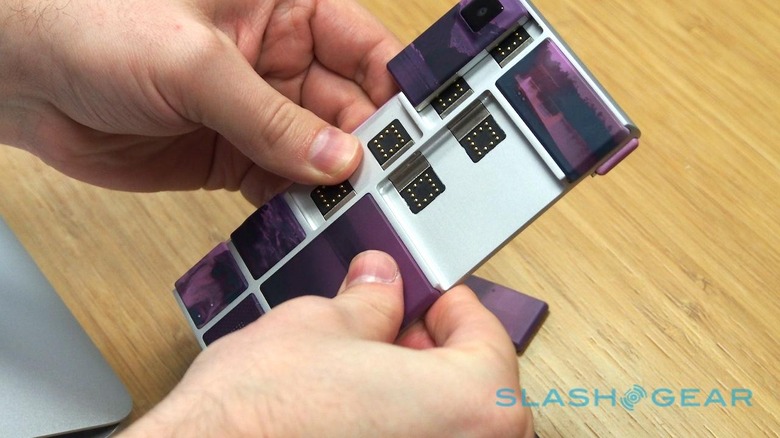

Google has given up on Project Ara, another of the company's more intriguing skunkworks projects shuttered without making the big waves the initial hullabaloo promised. Ara was to usher in a new generation of upgradable, wildly flexible smartphones: a platform that would both buck the trend of the relentless replacement cycle, and unlock possibilities for niche and custom gadgets that wouldn't make financial sense as a traditional device.

It's easy to gloat when you make an accurate prediction about the technology industry. It's less common to take the hit and admit that you got it wrong, even if – for the most part – the misses can be more frequent, if you look at the nitty-gritty details, than that you get correct.

Personally, I don't think I ever expected Ara to change the world, never mind the world of smartphones, but I did think it would reach the market in some form.

I believed in it for no small part because I respected the people leading the ATAP team. Regina Dugan, former DARPA chief and now poached by Facebook, is a blunt-tongued visionary, used to taking the unlikely and whipping it into something real.

Ara would, I guessed, launch as a developer device and, though take-up might be low, not only help shape the future of smartphones and tablets, but ease the way for high-end, niche features like Project Tango's clever but component-complex indoor mapping to be added to otherwise mainstream handsets.

The reality of modularity, though, has been a milquetoast one. LG's G5 has a scant handful of add-ons; more recently, Motorola has embraced the concept in the Moto Z, but prompted little more enthusiasm in the process.

NOW READ: Moto Z Hasselblad Mod hands-on

On the one hand, the add-ons are underwhelming. Motorola's Hasselblad camera Moto Mod, for instance, may have the storied name but you can't get its coveted quality for $250. If modular accessories are to be palatable then they need to be affordable, but it's tough to argue that you're not served better by a standalone battery pack, speaker, or projector that can be used with any device not just one.

That leads into the other big drawback: a lack of public commitment. If you can't be sure that the modules you buy today will work with the new phone you buy tomorrow, the incentive to invest in a platform gets a whole lot less persuasive. Motorola has probably been the most enthusiastic, saying that "Moto Mods purchased today will work with future generations to come," but falling short of putting an actual figure on just how many years of future phones it expects to have support.

I understand part of the reason why making that commitment is unpalatable, of course. Telling people you plan to maintain support for three, four, five or more years could lock you into a nightmare as a manufacturer if you subsequently decide you want to adopt a different strategy. Watching how much trouble Android OEMs have simply keeping their software up to date gives a taste of the challenge; doing so with hardware could be exponentially limiting.

It also locks you into the best of commercial technology today. Maintaining backward compatibility with old interconnects and module technology; running into the shortcomings of hardware that's two, three, or even more years old; being unable to embrace what's new and cutting-edge wholeheartedly, because you've always an eye on the past and what you still have to work with.

After twelve months, then, is a simple screen update really going to be sufficient to keep your modular Ara phone feeling in tip-top condition? Might you also need to replace the processor, and the battery, and the camera? At what point does – a little like the broom, the handle and head of which has been replaced so many times over the year that it's no longer the same implement – the core phone become a liability and a money pit?

Then there are the compromises. Slim phones sell, and yet individually wrapping each component in a separate shell is inevitably going to add bulk. There is efficiency in consolidation; a modular phone sacrifices at least some of that.

In the end, perhaps manufacturers have realized that it's far better for their bottom line to sell us a single, expensive phone every two or three years, rather than allow us to progressively upgrade for a fraction of that over time.

Shortly after playing with a prototype Project Ara device back in January 2015, I tempered some of my starry-eyed excitement with a reality check. Ara's potential, I pointed out, hinged on the content of its modules, the freshness of its hardware compared to what's available in the mass market, and just how flexible its bays would actually turn out to be.

Still, I concluded, the eagerness among ATAP and its external partners alike was there. That, I thought, was the guiding light for Ara on its path to at least some semblance of success.

It's a light that, today, has gone out. Project Ara has fallen to pieces, and though the geek in me is disappointed, the realist has to accept that it's probably for the best.