This Is The Largest Man-Made Moving Object In The World

From massive stone edifices like the pyramids in Egypt and the Great Wall in China to the high-tech (and incredibly expensive) International Space Station zipping overhead in low-Earth orbit, humanity has been driven to build big things since the dawn of time. No matter the locale, we feel the innate need to plant an everlasting metaphorical flag in the ground that says we've been here (and done that).

Back in the 1970s, Greek billionaire and shipping magnate Stavros Niarchos had a dream to construct an ultra-large crude carrier (ULCC) to add to his already monumental shipping fleet. Little did he know at the time that it would have a very colorful history and bear a jumble of different names. Even though it was eventually decommissioned and scrapped in 2010, the oil tanker he originally envisioned is still considered the largest ship — and man-made moving object — ever built. In fact, Guinness World Records lists it in three categories, including longest ship, largest ship by deadweight tonnage, and largest ship ever scrapped.

Japanese shipbuilder Sumitomo Heavy Industries began work on the "Oppama" in 1979. Its first official name is a reference to the Oppama, Jaopan shipyard where it was built, which itself had only been completed in 1971. What happens next depends on the source you read; Niarchos either went bankrupt and/or defaulted on the ship's payments. Another says he refused delivery because of vibration issues, while another claims he walked away because the shipping market had since taken a massive downturn. Whatever the scenario, the lore adds a nice dash of spice to this sea giant's story.

Its deck reached as far as the eye could see (almost)

The ship was sold in 1979 to a Hong Kong-based shipping magnate by the name of C.Y. Tung, who owned Orient Overseas Container Line (OOCL). Taking what Niarchos had started, Tung added several more feet to the overall length, which also increased its capacity. She finally launched in 1981 as the Seawise Giant, though she would later be renamed several times.

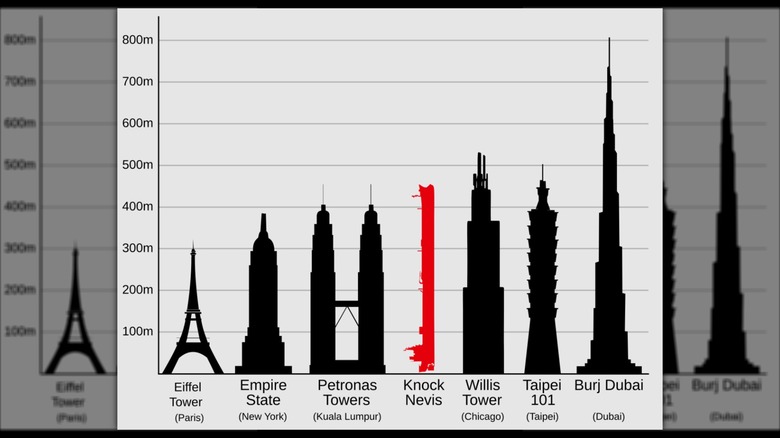

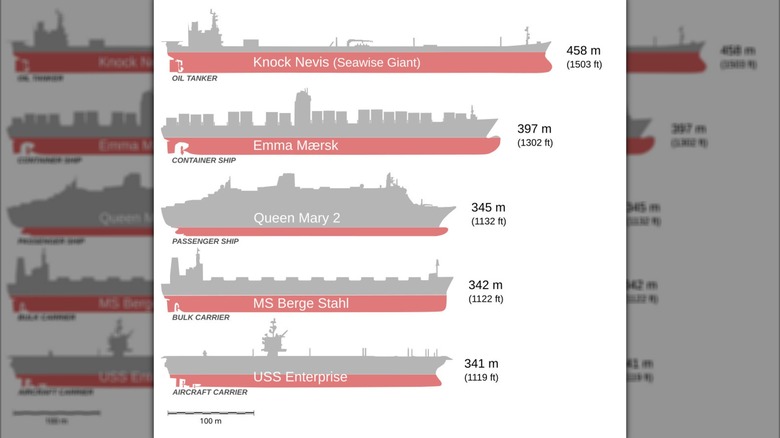

From bow to stern, she stretched 1,504 feet (over four football fields). If placed vertically, that's taller than both Kuala Lumpur's Petronas Towers (1,391 feet) and Manhattan's Empire State Building (at 1,453 feet). Additionally, the Seawise Giant makes every other ocean-going vessel pale in comparison. For instance, the USS Enterprise, the first of the U.S. Navy's aircraft carriers to bear that name, was just around 1,119 feet long. Even the the current champ of the seas, the MSC Irina, comes in at just shy of 1,312 feet.

With a deck measuring 339,500 square feet, the Seawise Giant was so large that it could take as long as 30 minutes to walk from one end to the other, so crew members used bicycles to get around. Her 46 oil tanks could carry over four million barrels of crude oil at once. Yet despite its prodigious size, it's not the largest container ship by capacity. That distinction goes to three different vessels from the Evergreen A class (Ever Alot, Ever Atop, and Ever Aria), all capable of holding 24,004 TEU (twenty-foot equivalent units, the standard measure of container-carrying capacity). Even still, the Seawise Giant's oil capacity is still staggering. The largest oil tanker currently in operation is the FSO Oceania, which can "only" carry 3 million barrels.

It was massive in virtually every respect

Other features of the Seawise Giant were equally impressive. Her rudder weighed 230 tons, the propeller tipped the scales at 50 tons, and a single chain link on the 36-ton anchor was heftier than an automobile. When fully loaded, she took nearly six miles to come to a complete stop and had a turning circle of over two miles. What's more, she was built with a one-inch-thick reinforced double hull and could withstand whatever Mother Nature threw at it without capsizing.

Unfortunately, her massive size was also the source of her biggest problem. She simply couldn't navigate through some of the world's most important thoroughfares, such as the English Channel, Suez Canal, and the Panama Canal, which takes most ships (even aircraft carriers) roughly 10 hours to traverse. Instead, she was forced to scoot around the Cape of Good Hope, and with a top speed of just 16 knots (18 mph), travel time was often lengthy. Still, her ability to move such vast volumes of crude oil made the Seawise Giant vital in the world's insatiable oil trade.

Incredibly, in 1988, she became a casualty of the Iran-Iraq War. While navigating through the Strait of Hormuz, she was hit by Iraqi missiles and sank in relatively shallow waters. Orient Overseas Container Line (OOCL) deemed salvaging her as too expensive and declared a total constructive loss. However, Normal International (a Norwegian company) spent millions of dollars (and 3,700 tons of steel) to salvage, repair, and return her to service, now christened as the Happy Giant.

The sea giant with numerous names and her very colorful life

Almost immediately after it relaunched the massive ship under a new name, Normal International was offered $39 million by Jørgen Jahre, another shipping mogul from Norway. Needless to say, it took the money. Jahre renamed the vessel Jahre Viking, and she returned to moving vast amounts of crude oil around the globe for another decade.

Technology finally caught up to the aging ship in the early 2000s as oil companies switched from using old, massive (and slow) bulk cruisers to much smaller, faster, and more agile ships. So, in 2004, Jahre sold the Viking to Singapore-based First Olsen Tankers, which converted her into a floating storage and offloading (FSO) unit, changing her name once again — this time to the Knock Nevis. She remained at the Qatar Al Shaheen oil field in the Persian Gulf for the next five years.

In 2009, this incredible ship's decades-long voyage came to an end when she was sold to a ship-breaking company in Gujarat, India, for dismantling — a far cry from how U.S. Navy ships are handled at the end of their life cycle. The Viking was so big that she had to be broken down into far more manageable pieces first, and in doing so was given one final name — Mont. It took 18,000 workers over a year to dismantle her entirely, all of which was turned into scrap. The only piece still intact is the 36-ton anchor, which is currently on display as a centerpiece for the Hong Kong Maritime Museum at its Jockey Club in Anchor Plaza.