The Largest Demolition Projects Of All Time

If there's a universal truth for most people on this Earth, it's that we watch with morbid fascination whenever something gets demolished. Whether you're in it for the spectacle, the technical achievement, or both, there's no denying that deconstructing massive or dangerous structures without collateral damage is a precise science. And, naturally, the bigger the better. Whether it be massive skyscrapers or nuclear power plants, the process of urbanization demands change — some changes being more drastic than others on a city's skyline.

Of course, it's not all fun and games; when its time has come, someone's got to wield the proverbial sledgehammer and destroy them safely, and someone's got to clean up the mess afterward. These projects typically require months or longer to plan out and execute, with teams comprising of multiple specialized crews handling everything from blueprints to explosives to cleanup — and the bigger the project, the bigger the cost in both manpower and money. What, then, are some of the biggest projects of them all? Where were they, and how exactly were these demolitions carried out? Let's break it down.

Before we begin, a quick word about our methodology here, namely the term "largest." This means different things to different people, from the most expensive to the most time-consuming, to the largest by volume, and so on. Moreover, it could also mean the most potentially dangerous or impactful projects. As such, we've taken into consideration multiple formats in our listing, discussing both the literal largest buildings ever demolished as well as the most expensive and hazardous. Plus, some buildings are simply too large to safely demolish with explosives; rather, they're deconstructed, piece by piece. We'll look at those as well, since their projects are just as intricate, if not more so, in different ways.

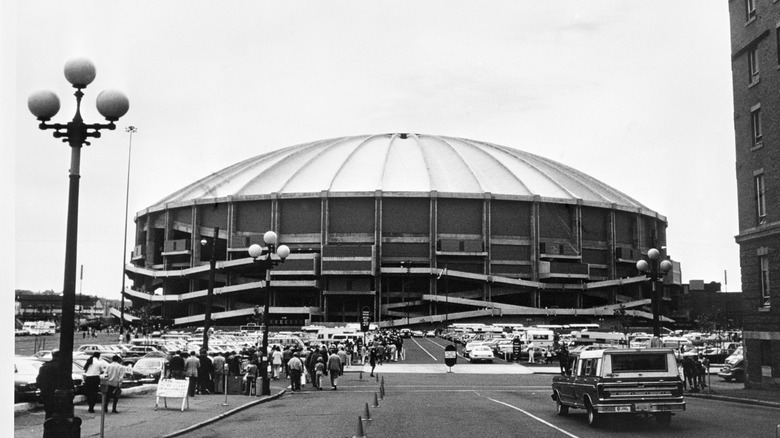

Seattle Kingdome: The largest structure demolished by volume (implosion)

Back in the 1990s and prior, the Kingdome, officially called the King County Stadium, was home to the Seattle Mariners MLB and Seattle Seahawks NFL teams. Its construction was actually quite tumultuous, subjected to a lawsuit to address cost overruns by the builders, to the tune of over $14 million in damages. However, the building made a quick recovery in the public eye, becoming a staple landmark of the Seattle skyline for roughly a quarter century. It was featured in various forms of media, including video games and TV shows, such as on the Seattle Circuit in various classic "Gran Turismo" titles and an episode of "Modern Marvels" covering the demolition.

Its various issues during its construction pale in comparison to the real problem: a flaw in the stadium's dome that compromised its structural integrity. The roof actually leaked since well before the stadium was opened, first showing signs of issues some three months prior to its completion. The roof had numerous repairs and updates in an apparently desperate and futile attempt to divert water from crucial weak points, likely made worse given Seattle's reputation for rainfall. This culminated in ceiling tiles crashing onto the field in 1994 during a Mariners practice session, signaling the beginning of the end.

Demolition wouldn't be trivial, given its proximity to historical buildings and the dome sitting above crucial water infrastructure. Dropping the concrete dome would've been disastrous, so contractors Controlled Demolition rigged small explosives to soften and break apart the roof as it fell. The plan worked perfectly, with the vibrations of the falling structure softened by the breaking up, as opposed to the dome falling as one massive piece.

J.L. Hudson Department Store: The largest single building demolished by volume (implosion)

The J.L. Hudson building was among the largest department stores by volume of all time, rivaling the Macy's on 34th Street in New York City. Its vast interior housed 2.2 million square feet of space that carried half a million items across 29 floors, making it the premiere shopping center across Detroit. It served customers from 1891 to 1983 and was notable as the tallest department store in the world throughout its tenure. The Hudson Building's history is actually littered with fascinating stories, such as the building serving as the fixture to which the largest American flag in the country rested.

Department stores such as these enjoyed massive booms in the 1950s and 1960s, with vendors from all over the world using the floor space to sell their wares. Think of it like a giant mall, with stores inside selling quality goods at a noteworthy location. However, the downfall of the building arrived with the subsequent downturn of Detroit. The city eventually became the largest American municipality to declare bankruptcy, posting an $18 billion debt and witnessing an exodus of automakers to states outside Michigan. Complexes such as the Detroit Arsenal Tank Plant were soon relegated to history.

With no money coming in and the city's general depopulation, demand for such a department store fell dramatically — as too did the building itself. Like the Kingdome, the Hudson building was demolished by Controlled Demolition, felling the structure on October 24, 1998. It was brought straight down by implosion due to proximity to other fragile, turn-of-the-century structures which could've created a domino effect if something went wrong. More impressively, all this was done without access to technical blueprints of the structure, since none existed.

WECT Television Tower: Tallest manmade structure demolished (implosion)

Typically when we think of tall structures, we picture skyscrapers like the Empire State Building and Burj Khalifa (a building that prompted Dubai firefighters to use jetpacks to fight fires). But there's one structure that dwarves even these: large radio and television towers, including the 2,000-foot tall WECT TV tower in White Lake, North Carolina. Towers such as these were placed all over the world back in the day, their height allowing the broadcasting of analog TV signals over vast distances before the rise of digital streaming. These towers were essentially massive steel antennae, extending around 2,000 feet tall to provide better coverage. They required constant maintenance, the lack of which can (and indeed has) result in their collapse.

Analog TV uses these towers in the same way that radio does — it broadcasts the stations over ultra-high-frequency channels that your TV tuned into, like a radio receiver. These channels were bought up by cellphone companies and ultimately led to a transition from analog to digital in 2009, when the FCC mandated that channels make the changeover to free up the bandwidth. An oversimplified way of viewing it is that cellphones simply replaced analog TV, and suddenly there was no need for such towers to exist.

This particular tower, standing at 2,000 feet, became the tallest manmade structure to ever be felled. It stood from January 1, 1969, to September 20, 2012, when it was demolished with 21 pounds of explosives. The land it sat on was donated to the Green Beret Foundation for wounded special forces soldiers, and the tower itself sold for scrap metal.

270 Park Avenue (JP Morgan): Tallest building deconstructed

While the WECT tower easily exceeds the old JP Morgan's 707-foot tall skyscraper at 270 Park Avenue, what's more impressive is that this particular building was demolished peacefully — that is, no explosives were used to fell the structure like how we typically picture these jobs. Instead, the building was dismantled piece by piece over the course of about a year. It was subjected to various extensions due to the pandemic, with demolition completing in 2021 and the subsequent construction of a brand-new zero-emission office building in its place.

Formerly known as the Union Carbide Building, the skyscraper was built in 1960 as the headquarters of the eponymous chemical company. Its proximity to Grand Central Terminal led to certain issues with the building's lower levels, owing to the vibrations of the near-constant movements of trains on the nearby rail lines. As such, 270 Park Avenue was constructed on massive columns poured between active rail tracks, resulting in its unique strutted appearance. It included an underground pedestrian walkway into Grand Central as well as approximately 11 acres' worth of glass.

These factors all compounded to create a nightmare scenario for the contractors; with so many external factors, such as historical structures, active rail lines, underground passageways, and more, it was eventually decided to deconstruct the building from the top down. This resulted in a lengthy but clean demolition, and 270 Park Avenue became the tallest actual building (as opposed to a radio antenna) ever purposefully deconstructed by the owner, surpassing the previous record held by the Singer Building in 1968.

K-25 Uranium Facility: Largest building deconstructed by volume

Once upon a time, the K-25 Oak Ridge uranium enrichment facility was the largest building under one roof in the United States, built in 1943 as part of the Manhattan Project. It was part of the larger Oak Ridge Gaseous Diffusion Plant, a complex that later became East Tennessee Technology Park. The building itself was U-shaped, covering a vast 44-acre plot of land measuring over a half-mile long and 1,000 feet wide. As its name suggests, the uranium enrichment plant was responsible for the separation of uranium-235 and uranium-238, forming weapons-grade uranium for use in nuclear missiles during World War II, and later the Cold War. With countries like India and Pakistan having robust nuclear programs, such buildings remain in-demand, though far less-so than during the mid-20th century.

It wasn't technically one single building, but rather a series of single units about 80 feet by 400 feet that were joined together. As such, the demolition process was relatively straightforward, just extraordinarily large and time-consuming, made doubly-so by the presence of exotic materials. It involved removing all the hazardous materials, equipment, and a remediation of various elements to ensure that the aging structure wouldn't collapse on its own.

Obviously one shouldn't blow up a uranium enrichment plant, so the contract called for peaceful deconstruction much like the JP Morgan building. Owing to its nature, some parts of the building were actually contaminated with radiation, meaning deconstruction had to be performed with segregation in-mind. Bechtel Jacobs Company, LLC began the deconstruction process in 2008, with original plans stretching to 2014 and costing an eye-watering $2.2 billion USD. Ultimately, however, the contractors finished the work one year early, saving approximately $300 million in the process.