The SR-71 Blackbird Can't Use Just Any Jet Fuel – Here's Why (And What It Uses Instead)

Helicopters don't all use the same fuel, nor do airplanes. Some types are rather standard, though, such as Aviation Gasoline for older propeller aircraft and models with piston engines. In addition, the most common type of fuel, used by helicopters and airplanes alike, is jet fuel A-1 (typically Jet A fuel in the U.S.). Military aircraft, of course, perform under a very different set of parameters than their commercial counterparts, and as such, modern models often use a fuel known as JP-8, or Jet Propulsion 8. This fuel includes additives like an icing inhibitor and antioxidant to improve a jet's performance in extreme environments, as military models must at times.

When the sophisticated SR-71 Blackbird was introduced, it required an entirely different type of fuel because of its incredible capabilities. The aircraft first entered service in January 1966 and was one of the world's fastest aircraft, capable of topping Mach 3. It wasn't just its extraordinary speed that made it impressive, but also the altitude at which it could fly: An extraordinary ceiling of approximately 85,000 feet. Achieving such feats put considerable strain on the jet.

It produced such high temperatures while in operation that it could have ignited JP-4 – the predecessor to JP-8 - rendering conventional jet fuel useless with the Blackbird. So a new fuel was specially created for it. The Blackbird's fuel would be known as JP-7. It doesn't sound like much of a departure from the existing fuel already in use by a lot of different military aircraft, but it had unique properties that made it Blackbird-safe.

The difference with JP-7 jet fuel

In a cockpit tour of the spy jet from pilot Richard Graham (via YouTube), he explains that the fuel flow gauges are "measured in thousands of pounds per hour." Engineers typically base fighter jet design around the concept of tremendous, fuel-wasting bursts of speed when they're needed, rather than a practical, functional level of speed, more common on a typical commercial flight. As such, engines simply drinking through fuel reserves is far from an exclusive trait of the Blackbird. For this particular aircraft to fly at all, JP-7 had to be developed especially for it.

A delicate balancing act had to be achieved in developing this new fuel. Decreasing its flash point too much would result in the opposite problem the unusable JP-4 had, and it wouldn't have the necessary chemical reaction to start the engine at all. The SR-71A Flight Manual (via Scribd) breaks down some of the difficulties: "This requires a fuel having high thermal stability so that it will not break down and deposit coke and varnishes in the fuel system passages." It goes on to state, "Other items are also significant, such as the amount of sulfur impurities tolerated. Advanced fuels, JP-7 (PWA 535) and PWA 523E, were developed to meet the above requirements."

The inspired solution to igniting the fuel was the injection of triethylborane, which is highly effective for ensuring fuel can both achieve and maintain a steady flame to dramatically improve engine performance.

The fuel and the engine that powered several extraordinary aircraft

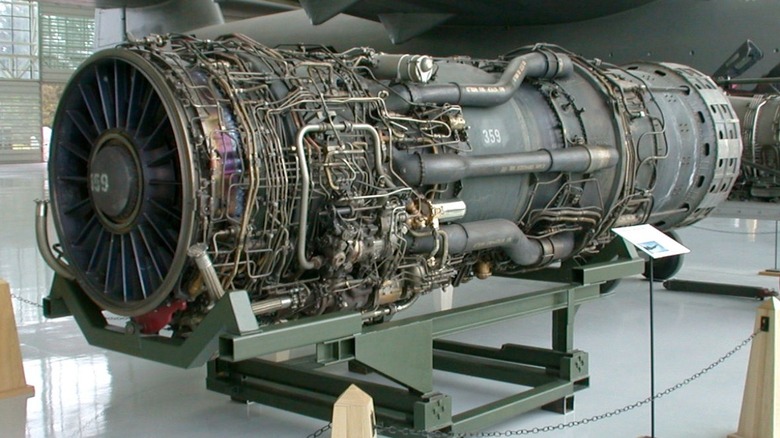

The raw power and performance of the Blackbird needed another essential component: a formidable engine. The Pratt & Whitney turbojet J58 was that engine, and it entered production in 1964. For use in the Blackbird, which first flew that same year, it needed to be able to withstand the heat as well as its fuel could. Utilizing the superalloy, Waspaloy, was one material that allowed the engine to do so. Pratt & Whitney also equipped it with a clever system that helped it maintain the Blackbird's tremendous speeds without pushing itself too far.

The National Air And Space Museum explains, "When opened, bypass valves bled air from the fourth stage, and six ducts routed it around the compressor rear stages, combustor, and turbine. The bleed air re-entered the turbine exhaust around the front of the afterburner where it was used for increased thrust and cooling." Engine power only accounted for approximately one-fifth of the thrust the jet used at speeds over three times that of sound itself.

Its predecessors in the family, the A-12 and YF-12 interceptors, also used the J58 turbojet, and though the A-12 is, technically, the only plane faster than the SR-71, it's still astonishing to think of the technological innovation that went into taking the most famous of the Blackbirds to those heights. The U.S. Air Force retired the SR-71 Blackbird in the late '90s, but it remains an aviation icon.