Why Airplanes Still Use Leaded Fuel

With the rest of the world having long-since moved away from leaded fuels, aviation gasoline, or "avgas" for short, seemingly exists as a final holdover from a bygone era. The most ubiquitous avgas available today is 100LL, which means 100 octane, low lead content. It's dyed blue and contains up to 0.56g/L of TEL, or tetraethyl lead, a common additive for gasoline back before unleaded fuel became compulsory. However, there are alternative types of fuel which don't contain lead, such as G100UL (general aviation 100 octane unleaded, dyed green). So why stick with leaded fuels at all?

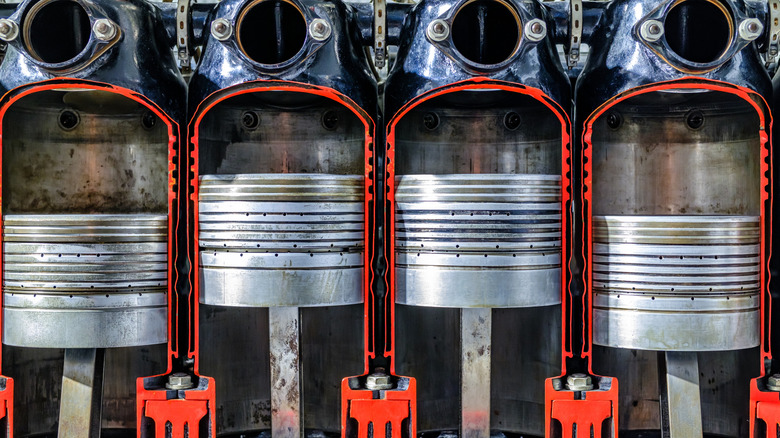

The short explanation revolves around what the lead does. Tetraethyl lead acts as an anti-knock agent, which means it helps avoid pre-detonation. Most engines are designed to operate within tight tolerances, with the fuel igniting when the cylinder is at or near top-dead center, resulting in an evenly distributed burn. Pre-ignition means that the combustion process happens while the piston is moving up and before the spark plug fires. The detonation then works against the piston. This can cause significant issues such as overheating and melting of engine components, and is one of the causes of engine knocking.

When you're flying an airplane, the last thing you want to happen is a bent connecting rod due to a detonation event, or an eroded piston face from pre-detonation; both can (and have) led to catastrophic engine failures. To help minimize the risk of such incidents, general aviation typically still uses leaded fuels because the additive acts as a preventative agent.

Why octane and anti-knock is so important

Leaded gasoline emerged in the 1920s, when aircraft engines were essentially just larger versions of car engines. However, once serious clinical studies regarding the developmental issues linked to leaded fuel exposure appeared in the late 1960s, the U.S. phased out TEL in cars throughout the 1970s and '80s. By January 1, 1996, leaded gas was banned from American stations — but not airports.

The problem comes from a matter of necessity. During this time, the Jet Age had just begun, gradually relegating piston engines to a niche market. Though there's no official word on why piston engine development largely stagnated, it's likely due to their general sidelining for these more advanced technologies, which use their own bespoke fuel types. However, that doesn't mean that piston engines ever went away; they simply remained relatively stable from a technical perspective.

Unlike car engines, aviation engines are designed to run at low rpms to keep the prop tips from spinning too quickly and produce peak engine horsepower at a fraction of most cars' rpm figures. These engines run higher compression ratios, which creates the potential for knocking if lower octane fuel is used. Because reliability is more important than anything else when you don't have the luxury of pulling over to pop the hood, the FAA still employs low-lead fuel as an operational safety measure. Lower octanes and unleaded fuels wouldn't work with some engines. That doesn't mean that there aren't alternatives: engines don't necessarily care where they get the octane from, after all, and some aircraft engines even run on diesel.

Are there viable alternatives to leaded avgas?

Yes, there are several alternatives, in fact, and this relates to what octane ratings actually mean. The higher a fuel's octane rating, the less likely it is to cause pre-ignition events. Therefore, on paper, any fuel that reaches 100 octane and burns similarly to 100LL can be used as a substitute. However, it was only in October 2024 that a 100LL-substitute unleaded avgas met the necessary criteria to be released for public sale, when GAMI's G100UL was introduced at Reid-Hillview Airport. However, the move to unleaded avgas is slow; the FAA, working in tandem with industry body EAGLE, is at the spearhead of this development, with three fuels being tested: 91/94UL by VP Racing, G100UL by GAMI, and 100R by Swift Fuels. So far, only GAMI has passed all certification processes.

Companies' move to produce, or at least experiment, with different types of unleaded fuels is a process mandated by an FAA deadline to stop using leaded avgas by 2030. Although sound in principle, this still requires a few key events to happen, namely: The mass-production of a safe and viable alternative, extensive testing of this alternative in higher-performance and vintage engines that might suffer from knock issues, establishing the infrastructure and distribution facilities for this fuel, and creating local and higher-level policies to enforce it.

While this may seem daunting, the FAA has been making strides towards implementing a lead-free fuel that's widely available. There is an up-to-date database showing every aircraft officially approved to run on G100UL, which can be found here.