Why Do Auto Brands Camouflage Unreleased Cars?

In the jungle, animals protect themselves from predators with camouflage, and the highly competitive world of automobile manufacturing is not so different. A camouflaged test car in the wild is an intriguing sight, with exotic, brightly colored patterns, or variegated black-and-white lines and shapes. If you're a fan of the latest in automotive design, you will no doubt have seen some of the extraordinary measures auto brands will take to keep their latest prototypes under wraps.

But are these highly stylized guises all about secrecy and protection, or are they merely attention-seeking marketing stunts? There is no reason why it can't be both. If online chatter and picture sharing amongst Instagrammers and influencers can build anticipation and interest around a new model, ad executives will seize that chance to create an online buzz around their brand.

An auto brand's marketing campaign may offer a glimpse of their prototype in action through a teaser campaign, or even a very public drive-by along the French Riviera, as Rolls Royce did in 2023. Brand executives used a beguiling cloud of text on the vinyl wrap of its camouflaged Spectre test car, with the words highlighting the brand's history and the mystique surrounding the possible existence of an all-electric Rolls. Also, when a prestige brand like BMW hands our motoring reviewer a prototype clad in a stylish, vinyl wrap couture, you can be sure that they know that we know it is all part of a marketing game.

Loose lips sink ships: the car manufacturing battleground

Such razzamatazz aside, with development budgets for new marques running into millions, if not billions of dollars, no brand wants to be pipped at the post by a lookalike alternative. Along with camouflaging their cars on the front line, brands also deploy cloak-and-dagger strategies like non-disclosure agreements, thoroughly vetting mechanics and designers — even hiring test tracks under false names. Writing at The Autopian, professional car designer Adrian Clarke says "Adding camouflage to disguise a test car is not a life-and-death matter in the same way hiding a tank is, but as a car designer I took the task just as seriously."

A spy pic of an unreleased car could earn a photographer up to $10,000 in 2016, but with the ubiquity of phones and drones, the golden age of the car paprazzi may be drawing to a close. As Clarke says, "These days smartphones and the internet have turned watchful enthusiasts into new model paparazzi."

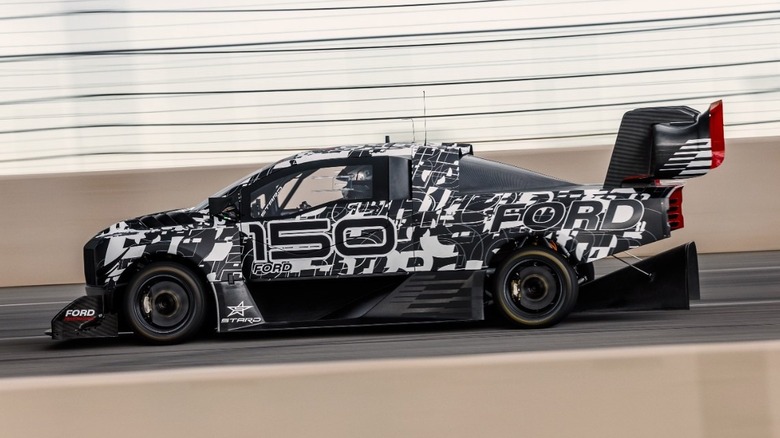

While car camo crackerjacks may not go to the same extremes as the US military, they will nonetheless adopt similar cloaks of invisibility to protect their secrets. A prototype of the GRMN Supra was caught at the Nürburgring in 2024 in a bra and diaper – industry terms for wraps that cover features at the front and rear of a test car – and more recently, the Mustang RTR prototype appeared in a one-off wrap inspired by naval camouflage.

That's a wrap! Surely those patterns fool nobody?

Humans tend to see three-dimensional shapes in two-dimensional images based on pattern recognition and visual clues like light and shade. This is how optical illusions can trick us so effortlessly: our minds fill in the z-axis blanks, seeing contours that may not be there. Illusions created by a vinyl wrap can help disguise a car's belt line and contours — particularly when trying to discern them from a two-dimensional spy picture.

But why bother with such deception? Car makers have their own test tracks, so why let their trade secret on wheels out on public roads? "Because at some point," Clarke explains, "the rubber quite literally has to hit the road." A test track cannot simulate the warts-and-all conditions — particularly the climatic environments — found in the real world. "Prototype cars need to be tested, tweaked, calibrated and generally flogged to death in extreme climate environments that would have sane people booking the next flight back to civilization," Clarke writes.

Camouflaged test cars are spotted everywhere from the -40º testing facility at Arjeplog, 34 miles from the edge of the Arctic Circle in Sweden, to the dry furnaces of Death Valley. The desert territory in southeastern California is in so much demand from carmakers that the park service issues special permits to test drivers going about their grueling work. It seems in the highly specialized and peculiar world of vehicle prototype testing, it is not just a jungle out there.