Was The Mazda 787B Really Banned From Le Mans? The Rotary Engine's Racing History Explained

Mazda's Wankel rotary powerplant boasts a proud and storied endurance racing career that began and ended in truly spectacular fashion. The rotary first took to a European circuit in anger in 1968, debuting in one of the world's toughest races: the 84-hour Marathon de la Route at the Nürburgring. Driving the Green Hell for three and a half days proved daunting, but Mazda impressively took home a remarkable fourth place with the Cosmo (one of the greatest Mazdas of all time), proving to the world that the Wankel could be both fast and reliable.

23 years later, Mazda represented Japan at the 1991 24 Hours of Le Mans, taking a tremendous upset victory — it was the first time a Japanese manufacturer won the infamous race. And it was a victory which should never have happened, but not because the engine was outlawed. In fact, the 787B was significantly slower than its competition, posting a qualifying time just over 12 seconds behind pole position. Rather, the 787B won through sheer luck, consistency, and reliability.

The FIA set the rotary engine's ban in motion in 1989 when the organization planned to restrict manufacturers to 3.5-liter reciprocating-piston engines for 1990. However, the FIA postponed these changes long enough to allow the 787B to compete, with rotary engines instead banned from 1992 onwards. Because of the timing coincidentally lining up with the 787B's underdog win, it's often misconstrued that the 787B was banned for being fast when, in reality, it was effectively a grandfathered-in exception to a rule that was already in place.

How the 787B raced when it should've been outlawed

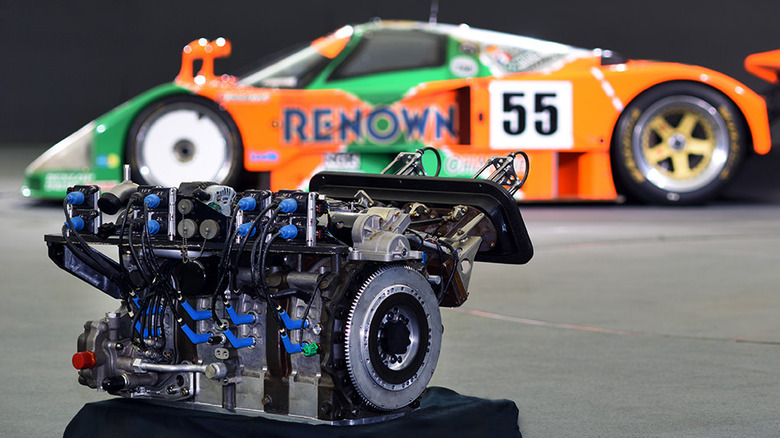

The regulatory bodies within the endurance racing world closed in on the rotary by the late 1980s, spurring Mazda into frantically developing its now-legendary prototype designs. These culminated with the 787B and its 2.6-liter R26B powerplant, a four-rotor monster producing some 700 horsepower and redlining at 9,000 RPM, making it one of the most powerful rotaries ever produced. Mazda pushed the development of this engine despite its previously uncompetitive nature because of various last-minute rule changes, which had more to do with logistics than anything else.

Back then, Group C racing and Formula One saw little overlap in engine development, with F1 fielding 3.5-liter naturally-aspirated engines following the 1988 turbo ban. Meanwhile, Group C saw a combination of large-displacement naturally-aspirated and forced-induction engines competing in a mixed grid, meaning there was almost no shared development between these two series. Group C's new 3.5-liter displacement restrictions deliberately mirrored F1's in a bid to attract more private teams and promote fuel efficiency, effectively ending Porsche's dominance with the turbo 956 in the process.

The rule change stipulated that no rotary-engined cars would be allowed to compete after 1989. However, because most teams couldn't develop reliable engines in time for the 1990 season, the rules were postponed to allow existing teams, including Mazda, to utilize their original engines while they developed compliant powerplants. The company doubled down on its rotary-powered swan song for 1991, the final season that allowed rotary engines — which is how Mazdaspeed managed to slip a Wankel engine into a championship that, on paper, had banned them.

The Mazda 787B's race record and sole European victory

Mazda's rotary engine rarely found itself in the lead, and the R26B was no exception. Throughout the FIA World Sportscar Championship, Mazda saw the podium two times and won exactly one race of the 14 it started: Le Mans. It was competitive at home, taking a class win at the 1991 Fuji 1000km, for example. But Mazda's car struggled against competitors like the Sauber C9, which held the top-speed record at the older Circuit de la Sarthe before its chicanes were added. Mazda had built the R26B engine with the old circuit configuration in mind, but the new chicanes added in 1990 meant that it was once again outclassed that year.

But while all the other teams switched to developing 3.5-liter powerplants in anticipation of the 1992 season, Mazda committed to its rotary for 1991, seeing as it was the engine's last year anyway. So, instead of going for outright speed, Mazda tuned the 787B's engine for reliability, so much so that it showed effectively no signs of wear following the 24-hour race.

Mazda entered its ultra-reliable 787B alongside competitors that either broke down or were saddled with penalties due to being over the displacement limit. This provided the racing community with a rare moment in which all the stars perfectly aligned for a true upset victory, and an upset it certainly was. Nevertheless, the rotary engine's reliability proved itself the rightful winner that day, and Mazda cemented its 787B as one of the all-time motorsports legends — but not because it was fast.