2024 Morgan Super 3 Review: Three Wheel Fun Comes With Compromises

- Burnouts for days

- Classic style with modern engineering

- Spectacular shifter and clutch action

- Less embarrassing than other three-wheelers

- Still combines the worst aspects of cars and motorcycles in one package

- Go right ahead and forget about comfortable cruising

- Inexplicable solutions to simple problems abound

- Borderline hilarious pricing

The legend of Morgan Motor Company always occupied a little niche in my mind. Lightweight sports cars, retro styling, and even stories of wooden body frames surviving into the modern era? Yes, please, if I do say so myself. But I never drove a Morgan, neither a classic nor one of the late models built before the company abandoned the United States back in 2008.

Times change, old chap, and Morgan now plans to revamp the American market with a fleet of brand-new old-timey sportsters eligible for importation under the Low Volume Motor Vehicle Manufacturers Act. First up arrives the Super 3: as the name implies, a three-wheeler in classic boattail style. Critically, three wheels and a weight below 1,749 pounds means that Morgan can classify the Super 3 federally as a motorcycle.

Here in California, that means helmet laws do apply, similar to the Polaris Slingshot, Vanderhall Venice, or Can-Am's Ryker and Spyder duo. As much as I abhor wearing a helmet and a seatbelt simultaneously, I jumped into this Super 3 loaner surprisingly stoked to experience what looked like some serious silliness.

First impressions of a new three-wheeler

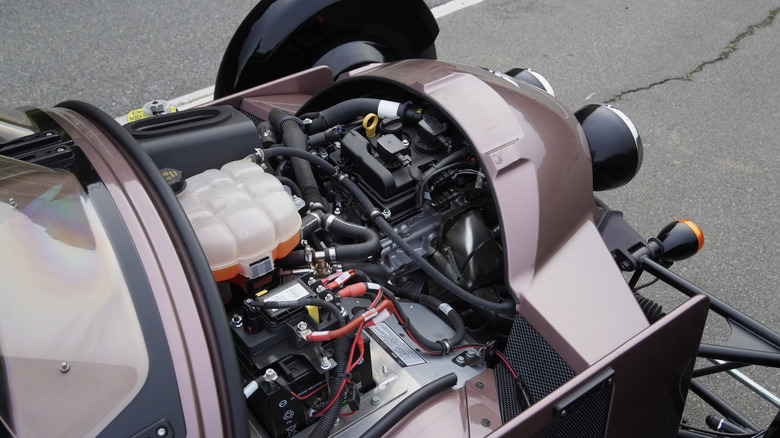

I picked up the Super 3 from Westside Collector Car Storage, where the barking little engine bounced off cinderblock walls with an echoic roar. Alright, Morgan, maybe this little trike gets a bit more serious than expected. And the engine, turns out, returns the Super 3 to an historically significant partnership with Ford—in this case, a naturally aspirated 1.5-liter three-cylinder engine borrowed from the Focus ST. The mill replaces older Morgan three-wheelers' V-twin engine, likely in a nod to Euro emissions regulations since, here in the US, a BMW motorcycle engine might very well perform better.

Still, the Ford triple puts out 118 horsepower and 110 lb-ft of torque through a five-speed manual transmission also borrowed from another manufacturer, in this case from the MX-5 Miata. A carbon-fiber-reinforced belt then sends power to the single rear wheel. And if those power stats sound underwhelming in the era of 1,000 hp hypercars and restomods, keep in mind that the Super 3 enters the fight weighing in at a svelte 1,400 pounds.

Power-to-weight ratios go right out the window

Pulling out onto the roads of Gardena immediately revealed how quickly power-to-weight math leaves the chat while driving a lightweight stick-shift three-wheeler without power steering or driver aids. I took the first couple of stoplights easy, letting this piece of British engineering warm up as my own processing power began computing shifter throw and clutch weight and suspension feedback. But the devil at my elbow started whispering and soon enough every pull brought on burnouts off the line, then little chirps between first and second gear, and finally a bit of squiggle even between second and third.

Turns out power stats mean nothing on a featherweight trike trying to harness 118 horses with only a single rear all-season tire that measures 185 millimeters wide. And no traction control, mind, to prevent the kinds of shenanigans that Formula D teams spend hundreds of thousands of dollars to produce at whim. Slot that alu shifter right into first, push into the nice firm throttle, and simply let off the clutch. But prepare for immediate oversteer, easily corrected by flicking the steering wheel into the opposite corner, as the drivetrain's weight over the nose geometrically prevents full spins—unless intended, I say. With a narrow 72-inch track width for the front two tires, playing these games at right turns never even chances sliding into another lane.

The incessant, irresistible urge to peel out only gives pedestrians another reason to stop and stare. Of all the cars and bikes I've ever driven and ridden, the Super 3 attracts the most attention, bar none. The quick evolution in my driving style notwithstanding, Morgan's retro design and that mesmerizing opalescent pink definitely do the trick equally as well. All roll hoops and aero discs and boatttail lines, brushed aluminum trim and quilted interior leather, my modern carbon-fiber helmet standing out like a sore thumb... Who could blame them, when this kind of fun rolls past?

Modern engineering from Morgan Motor Company

Meanwhile, serious engineering takes center stage, too. Unlike those wooden frames of old and other modern unibody cars, the Super 3 actually uses a true aluminum monocoque with stressed exterior surfaces and chassis castings that serve simultaneously as engine mounts and air ducting. The entire drivetrain sits behind the front axles, inboard coilovers handle damping, and a rear chassis clamp also allows for the rear cargo lid to hinge upward.

Keeping track of everything from the cockpit requires a certain seat-of-the-pants confidence. But actually fitting the seat of my pants into the Super 3 took a bit of work. Cold and foggy weather—almost British, come to think of it—dictated warm clothes including a leather motorcycle jacket. And there's simply no way to get in with any sense of panache. First, I stepped onto the seat bottom with both feet, leaving plenty of residue for my pants to soak up. Then, I slid my legs down awkwardly around the steering wheel into the pedal box. Fastening the seatbelt, which travels from an inner pulley to an outer buckle, required removing my helmet.

Adjusting to the Super 3's tiny cockpit

Once strapped in, I pulled a hidden lever beneath the steering wheel to pull the column out into place. Another grasping tab fully under the dash allowed me to slide the pedal box further forward (all of this necessary due to seats that slide neither forward nor aft, nor allow for any adjustment of recline). At 6'1" and 170 pounds, my right hip rode constantly elevated on the central transmission tunnel, helmet fully exposed to wind rushing over the low screen, and left knee either bumping constantly against the aluminum pedal box sidewall or, with the pedals a little closer, perfectly on a painful eye-loop that provides a borderline hilariously useless reference to some kind of an elastic storage system.

Finally in place and situated, ready to drive, I slipped the key in directly below the steering column—rueing the dangle of various accoutrements on the keyring, but more on that later—and flipped up a fighter-jet start button cover almost reminiscent of Lamborghinis. Crank the key, push in the clutch, finger the START button twice, and the Ford engine roars to life. Dual digital gauge screens on the dash centerline fired up, the nearest showing an unknown set of bars on the left, a central numerical readout for RPMs that evaporated quickly into nonsense, and fuel quantity on the right. The right gauge shows speed and a tiny odometer count.

Waterproof gauges and switchgear

Below, actual physical switches control the hazard lights, horn, and headlights. Otherwise, the minimal half-hoop dash of textured plastic houses only a few lower, almost hidden, buttons for seat heaters, a blower fan, and a USB outlet. (A mount for phone accessories apparently lurks under there, but I never found it.)

The seat heaters came in handy immediately on the drive home and during some canyon rips up to Malibu, as low-50s and then high-40s weather presaged an oncoming atmospheric river storm. My Spidi jacket, battened down with buckles tightened at the wrists, and the 6D helmet kept most of my body from exposure to the wind, but for the first time in my life I started thinking that motoring gloves might have been a good choice, too.

Inexplicable engineering decisions abound

The freeway drive home and time in Malibu revealed some of the interesting engineering decisions that Morgan made while trying to deftly navigate the demands of classic motoring style meeting modern performance expectations. To an extent, choosing to lean toward one or the other might have served the Super 3 better. On the Pacific Coast Highway, I wanted to cruise in comfort, listening to music through my Cardo Packtalk Edge helmet speakers. But the suspension rides too firm for such daydreaming, and the front wheel design catches wind better than most catamarans at speeds over about 50 miles an hour.

Given the lack of power steering, controlling the Super 3 at speed becomes something of an effort. But if trying to hold a straight line at 80 mph takes some muscle, picking a line to apex and holding it while braking, downshifting, and then cornering hard requires serious exertion. At no point did I figure out whether keeping my left elbow outside or inside the monocoque worked better. Maybe a smaller diameter choice of Mota-Lita steering wheels might allow more space for appendages—arms and legs—but then any potential leverage decreases while hauling through turns, too.

Getting a workout behind the wheel

As my arms put in work, my spine absorbed harsh impacts constantly. The prospect of smaller wheels and higher tire sidewalls entered my mind. After all, sacrificing a bit of rigidity at the edge of traction seems a worthy trade-off for general comfort in a three-wheeler that inherently suffers from an otherwise already enjoyable lack of traction. Instead, the oversprung suspension jounced and clunked off dips and bumps, while I wrestled with the steering wheel and tried to keep my legs braced in place by pushing my left heel into the hinge of the clutch pedal.

At a certain point, I began holding the wheel at 12 and 3 o'clock, downshifting early and upshifting late right before the Ford engine's 7,000 rpm redline. Something asymptotically approaching a rhythm set in, and I dipped into a level of pace and focus typically reserved for track sessions. All while going slower than slow, but feeling spectacular about it. Interesting, or at the very least worthy of observation, my third-level conscious mind noted as I eased further and further into throttle earlier and earlier into turns. Will we start drifting or will the better angels of our nature take the reins? In the Morgan Super 3, these kinds of decisions require serious consideration.

Concessions to weight savings

I kept pushing. Faster and faster until the rush of frigid wind and inescapable belt whine brought the fun to a climax. As usual with three-wheelers, the Morgan begs for more without truly being able to handle the limit. Is that the point? Maybe. But only on that ragged edge does the whole package coalesce—unfortunately, the rest of the ride to and from requires serious sacrifices in comfort and convenience.

Maybe Morgan should have scaled up the Super 3 by about 10%. Give those elbows a bit more space, taller sidewalls to absorb the harsher impacts, even a dead pedal and some padding for the driver's knee—all would go a long way toward making the Super 3 liveable as a cruiser and ripper at the same time. More space in the engine bay, and maybe easier access to the rear storage compartment rather than requiring a custom tool on the keyring to ride along at all times (the aforementioned accoutrements dangling below the steering wheel and between my knees), which spins out peculiar screws to remove the rear cargo rack and requires a hilarious bit of forearm and finger strength.

But making those changes then brings up weight concerns, potentially bumping this little trike up into federal classifications that require hefty concessions to safety regulations. At least now, visibility is excellent.

The best of three-wheeled motoring

Perhaps most importantly, how does the Morgan Super 3 compare to those other three-wheelers on the market today? Well, I've still never driven a Vanderhall—the truest Morgan ripoff from a Utah-based company that's probably a bit nervous Morgan decided to return to the US market. And in honesty, all three-wheelers to an extent combine the worst aspects of cars with the worst aspects of motorcycles. Exposed components durable enough to handle weather result in overly plasticky textures. Build quality tends to lean toward cheap and rattly. And just go ahead and forget any semblance of comfort.

The fact that driving a Super 3 in California requires wearing a helmet and safety belt simultaneously blunts some of the enjoyment factor, without a doubt. And yet, the low windscreen and Cardo setup left me happily listening to music and taking calls—otherwise impossible given the lack of a stereo or even a place to conveniently leave my phone while driving.

An eye-popping pricetag for an eminently fun toy

Everyone but retired dentists can agree that Can-Am's three-wheelers deliver every awful aspect of riding and motoring in the worst possible combo. And with "only" 118 horsepower, the Super 3 falls well short of a Polaris Slingshot's radical nature. But I'd still take the Morgan over either, if just for the classic style that commands an evidently different type of attention. In that regard, is a new Morgan better than a real classic Morgan? Hopefully, a level of improved reliability thanks to 21st-century engineering will pay off.

Then there's the eye-popping, borderline ludicrous $53,937 starting price tag. But it's just money, darling—or so my consumer's mind retorts. Similar to a Slingshot, wouldn't about 20 grand sound much more reasonable for something that so solidly approaches boy-toy status? The pricing makes Morgan's approach to modern America entirely baffling.

Simple arithmetic suggests that the promised four-wheelers on the way might well knock knees with Porsche 718 pricing, presenting an entirely unreasonable proposition in every regard from performance to reliability and daily livability. Bumping up to four wheels brings up those safety regulations, which may require sacrificing some of the analog appeal. And Morgan can't afford to lose any of the whimsical spirit that, despite such obvious flaws, makes the Super 3 so much fun to drive.