USS Monitor & CSS Virginia: The Duel That Changed Naval Warfare

The 19th century was a time of dramatic global transformation. Monarchies were falling and democracies sprang up to replace them while many remaining monarchs saw their power diluted in favor of popular government representation. The Industrial Revolution started with the ideas of a few clever inventors and studious engineers, while political boundaries shifted and the Europeans traveled abroad in the scramble for Africa, intent on colonizing the entire continent. So many facets of life changed that it can be hard to keep track. However, one thing that remained a consistent feature of the era was military conflict and conquest.

The United States clashed with European powers during this period, but it would be a matter closer to home that sent its people into turmoil, namely the Civil War. Because of the nascent Industrial Revolution in the period before conflict broke out, many new weapons and ever more powerful military hardware became available to the factions that would soon be clashing with one another. Not only were cannons becoming more powerful, inventions such as the Gatling gun made fighting faster and more brutal than ever. At the same time, naval warfare was undergoing a transformation, as the steam engine began to intrude upon the sailing ships that had dominated the sea for centuries. A clash of modern technologies highlights a significant moment in the Civil War — the duel between the USS Monitor and the CSS Virginia that changed naval warfare forever.

Union naval blockade

The American Civil War was primarily a land conflict of ever-changing lines splitting North from South. Yet both of the warring parties held extensive coastlines as well as inland waterways where battles inevitably broke out, making naval operations integral to the fight on each side. As part of its tactics, the Union Navy enacted a blockade of the southern coastline to prevent imports and exports that would benefit both the economy and the war effort of the Confederacy. While blockades had long been a useful military tactic, this was the first to be initiated by the United States, remaining the largest blockade by the country until WWI.

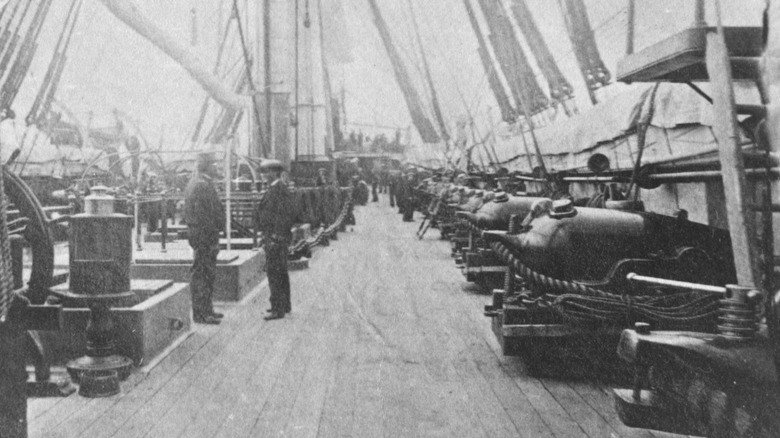

To enforce this blockade and attain legitimacy among neutral states, the Union Navy had to enforce it with ships at all 189 ports of the Confederacy, but only had 42 ships with which to do this. After declaring the blockade, the Union Navy immediately set to grow its forces by readying any ship in its fleet and quickly building more. To boost its numbers, merchant vessels were also converted into warships, eventually building up a fleet of 500 vessels. Despite this, many shipments slipped through the lines and the Confederacy continued to equip itself, although foreign trade suffered heavily.

Hampton Roads

Sitting slightly inland off the southern coast of Virginia sits Hampton Roads, a roadstead with excellent protection from the open ocean formed by the deepwater estuary of the James River. Its geography makes it a perfect natural harbor and has been used as such throughout the history of North American settlement. A channel continues inland for 45 miles, providing transportation far into mainland Virginia, and the area is home to Norfolk and Portsmouth to the south, with Newport News and Hampton to the north.

Shortly after the April 12, 1861 attack by rebel forces on Fort Sumter that initiated the Civil War, formal secession of Southern states followed. President Lincoln responded by ordering a naval blockade. Gosport Navy Yard was on the south side of Hampton Roads and, fearing its takeover by rebels, its ships were ordered to be sunk and were set ablaze. While nine ships were destroyed, the Union lost control of the largely unscathed port, with more than 1,000 pieces of artillery and large quantities of gunpowder falling to the Confederates, along with the Norfolk Navy Yard. Despite this loss, the Union retained control of the entrance to Hampton Roads, effectively cutting off the lost ports from the open sea. This stand-off situation would continue as the Union blockade commenced on April 30, 1861, and remained in force on March 8, 1862, when this historic battle began.

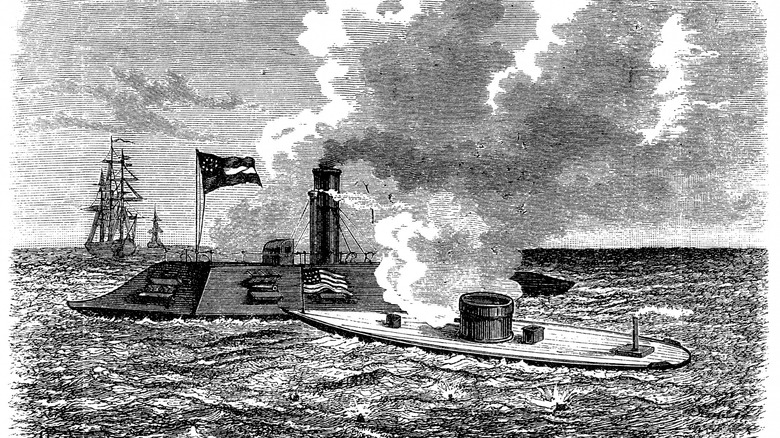

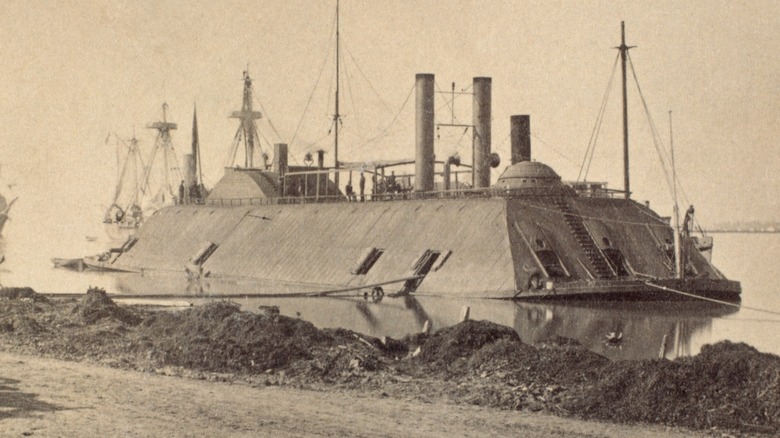

CSS Virginia

The destruction of the Gosport Navy Yard was accompanied by a hasty retreat. Much of the port remained intact and full of supplies and not all of the ships were completely destroyed. Among them was the steam frigate Merrimack, which was fitted with a screw propeller powered by a steam engine. Launched in 1857, sailors soon discovered it had a tendency to roll and the engine was problematic, leading to it being placed in ordinary (storage) at Gosport.

By May, the Confederates were planning a new type of warship, reinforced with iron, and raised the Merrimack for this purpose. They then removed the damaged upper section of the ship — the hull and engine remained largely undamaged — and cut a horizontal line at the berth deck from end to end. Workers then built a structure atop the hull for fitting the armor and adding extra strength and protection to the ship. This structure made up the 172-foot casemate, with sides sloped at 36-degree angles and covered with 2-inch-thick armor. The casemate housed eight three-caliber guns and was provided with explosive ammunition meant for the destruction of what they believed would only be wooden ships. However, a massive iron ram was mounted to the bow to cut through any armored ship it encountered. The amount of iron used added significant weight for which the engine was not designed, making the ship slow and lumbering. The crew was to rely almost completely on the strength of its armor for protection, as fleeing from battle would be impossible.

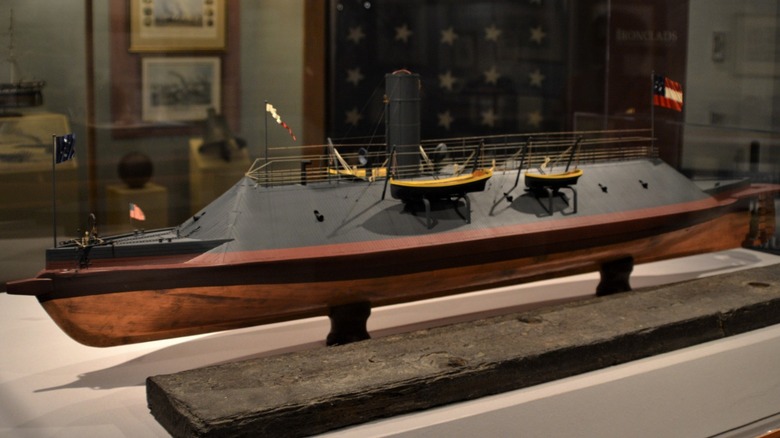

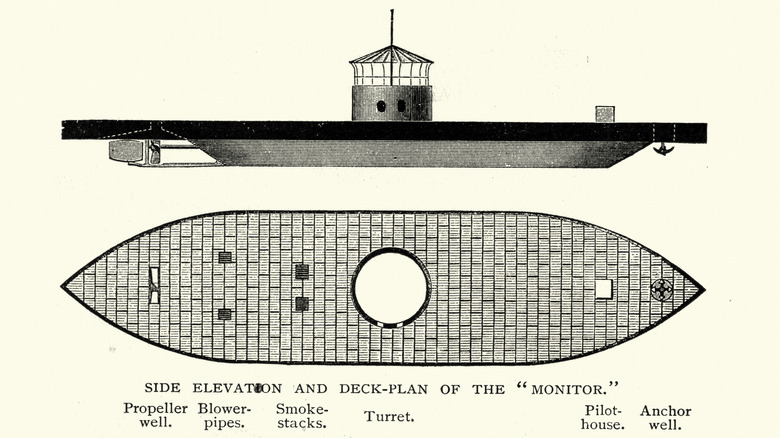

USS Monitor

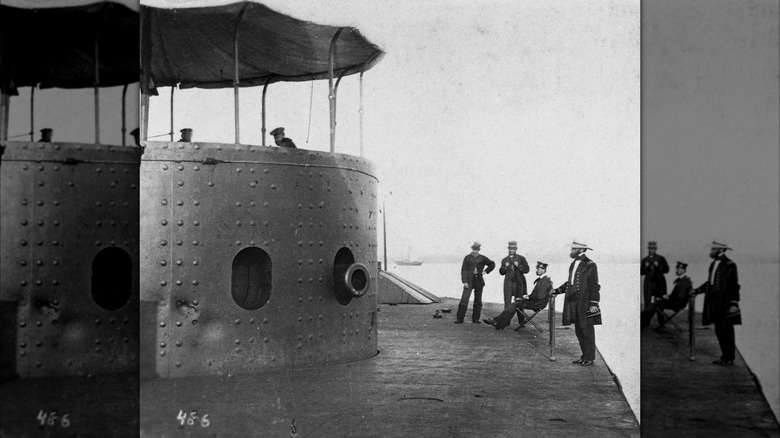

Ironclad warships had already been produced by France and England by 1861, and when President Lincoln received word of the Confederates building one of their own, he gave the order for the Union Navy to have its own ironclads. Swedish-American inventor John Ericsson brought forth a novel plan for a ship made almost entirely of iron that would feature a rotating gun turret that could be aimed without turning the whole ship. Although he encountered some resistance, his plans were nonetheless accepted and construction began.

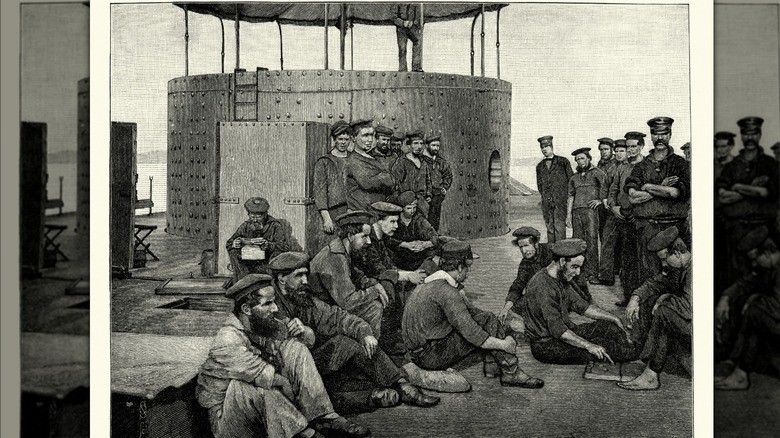

The design of the boat was more akin to a raft, as it was shallow and sat low in the water. It was ill-suited for sailing at sea and would be used for littoral operations only. The huge iron turret only carried two guns, which was unheard of at the time but could have the effect of many more because they could be rapidly reloaded and aimed in different directions without turning the boat itself. Seven inches of iron plating covered the entire vessel and the flat deck sat only a few inches above the waterline, giving little for the enemy to target with their guns.

The Monitor was completed in only 101 days, weighed 1,000 tons, and was 180 feet in length. Its screw was powered by a large steam engine and a smaller one operated the rotating turret. Top speed of six knots was attained in trials but steering proved to be almost impossible. However, a quick fix was devised by Ericsson, and the Monitor was repaired and certified for service on March 6, 1862. Despite this, the Monitor was not perfect, and many problems appeared throughout the ship. Nonetheless, expediency was an overarching priority, and its crew would have to cope with any deficiencies on the go.

Hampton Roads battle, day one

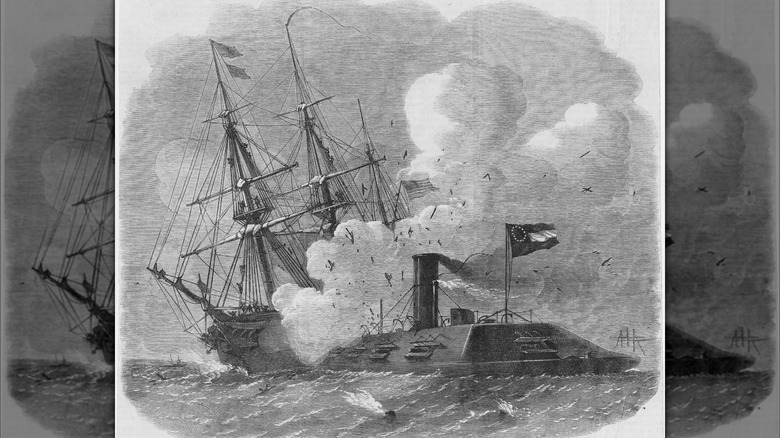

March 8 of 1862 began like any other for the Union soldiers patrolling the blockade of Hampton Roads. What was typically an uneventful duty quickly changed as the newly launched CSS Virginia crept up toward the Union naval contingent of five warships blocking access to the open sea. Virginia first set its sights on the USS Cumberland, a 24-gun sailing sloop. As it approached, several Union ships fired on the Virginia, only to see their shells bounce off of the thick steel casemate and fall into the water. Shots were fired at Cumberland from up to a mile away, destroying one of her guns. As the Virginia drew ever closer, it finally crashed into the Cumberland with its massive ram tearing through the sides, utterly destroying the hull. Although this attack removed the Cumberland from the battle, the Virginia's ram was torn off, and the bow twisted.

Virginia's next target was the 50-gun sailing frigate USS Congress. Congress attempted to flee to shallow waters but ran aground with the Virginia closing in rapidly. Two hundred yards from the Congress, Virginia opened fire, causing grave damage to the massive ship, and causing 120 casualties to the 400-man crew. Sometime after engaging the Congress, Captain Buchanan of the Virginia was wounded during the battle. Yet his ship had taken out two mighty Union ships while taking only light damage, so the Virginia retreated to regroup and prepare for another battle the next day.

Hampton Roads battle, day two

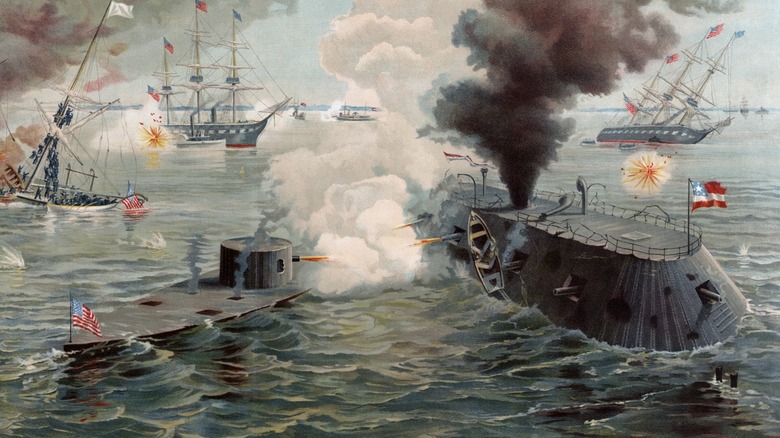

After its first day out, the CSS Virginia anchored at Sewell's Point on the southern side of Hampton Roads overnight. The jubilant crew celebrated and then planned for the next day's excursion. But little did the crew know that the newly launched USS Monitor had been making a perilous journey toward Hampton Roads. The shallow boat wildly rolled from rough waters, causing seasickness compounded by accumulating carbon dioxide due to failed ventilation fans. She had to be towed to shore. But on March 8, 1862, the calm seas prevailed, and the Monitor made its way to Hampton Roads.

The Virginia set out again around 8 a.m., ready to target more Union ships. The ship headed for the USS Minnesota for its first attack, but as it made its approach, the crew spotted an unfamiliar sight floating nearby. Just as the Virginia started closing in on its target, the Monitor appeared between them as gunfire passed it and struck the Minnesota. A second volley struck the Monitor, only to bounce off its armor and fall into the sea. The Monitor was smaller, faster, and could fire in almost any direction, posing a real threat, even though it had only two guns. Virginia attempted a ramming maneuver, succeeding only in grazing the Monitor as it quickly steered away. The Monitor replied with its own ramming maneuver, but a steering failure aborted the attack. This tit-for-tat continued until the Virginia scored a direct hit to the Monitor's pilothouse, blinding the pilot. Eventually, the Virginia left to avoid low tide and returned to its base in Norfolk. Each crew believed they had won this round.

Second Hampton Road battle

On April 11, 1862, the CSS Virginia once again sought to move into Hampton Roads and engage the Monitor. Knowing what to expect this time, they had hatched a plan to capture the vessel and take it to Confederate territory. While positioned near Sewell's Point, the Virginia exchanged fire with the Monitor from a distance, hoping to lure it into a close-quarters fight. With the aid of three captured merchant ships, the Virginia crew had planned to board the Monitor, take control, and tow it back.

On May 8, the Monitor sailed toward the Virginia. The accompanying ships were ordered to stay back and slowly sail back toward Fort Monroe while the crew of Virginia waited for the opportunity to board. The Monitor did not take the bait, instead remaining at a safe distance. The Virginia would not have another chance at its adversary as the Union took control of Norfolk on May 11, 1862.

Aftermath

The CSS Virginia had been victorious by removing two Union Navy frigates, the USS Cumberland and USS Congress — a significant loss. Moreover, the objective of the USS Monitor was to protect those ships from the new ironclad built by the Confederates, which it did not do. The battle was a slow-moving affair as both boats were very slow, especially by today's standards. While the Monitor had a speed advantage, it was still barely more than a snail's pace. Furthermore, both ships encountered serious difficulties.

At one point, the Virginia ran aground and, trying furiously to flee from an attacking Monitor, almost blew its boiler from temperature levels as the crew pushed it to its limits. The Monitor managed to get a shot in point blank before it broke free but did not cause major damage. Over the course of four hours, the Monitor took 23 hits and the Virginia received 20. Both boats were still afloat as the Virginia retreated.

Although the battle was essentially a draw, the Confederacy felt it had gained a better position on the south side of Hampton Roads. Furthermore, the Union had prevented the decimation of its fleet at Hampton Roads. As flawed as both of these vessels were, their iron shells prevailed and prevented them from being lost.

Legacy

The battles between the CSS Virginia and the USS Monitor played only a small part in the Civil War. Nothing decisive happened those days, and the loss of two Union ships, while painful, was not devastating to the cause overall. However, in the arc of the history of technology and its use in warfare, this was a significant event. For the first time, two ironclad ships went up against each other and proved how much more difficult they were to sink with existing gun technology.

As the Confederates retreated under Union shelling from Sewell's Point, they detonated munitions inside the CSS Virginia, destroying the vessel completely. The Monitor was upgraded and repaired after the battle, continuing to serve blockade duty afterward. On December 31, 1862, the USS Rhode Island was towing the Monitor toward a blockade at Wilmington when they were caught in a strong storm by surprise. Rough seas and high winds eventually caused the Monitor to take on water and sink below the waves.

Throughout the remainder of the war, both sides put forth concerted efforts to build more ironclad ships, with navies beyond American shores doing much the same. This showed that wooden ships powered only by sails were fast becoming obsolete as warships. Indeed, ironclad technology developed at such a rapid pace that the last battle between wooden ships occurred in 1864, ushering in the modern era of naval warfare.