You're Overestimating Google's Driverless Cars

Never tested in snow or heavy rain, potentially ignoring police, and confused into swerving by crumpled newspaper: Google's self-driving cars face more than a few lingering problems before they're truly ready for the road. The search behemoth's plans to start tests of its control-free "pods" out in public had already collided with California's DMV, which demanded that at least rudimentary steering and pedals be fitted before they'd be road-legal, but that may only be the start of Google's headaches.

In fact, exactly how advanced the autonomous car technology is, and how capable it's perceived as being, are two very different things, it seems.

The challenges Google faces are twofold, concerning both what data the vehicles require before they can map out a route, and how they react to unforeseen occurrences while actually in motion.

For instance, the cars can spot "almost all" stop signs, project lead Chris Urmson confirmed to MIT Technology Review, and would react to them appropriately, but would not recognize a traffic signal it had not been prepped to identify. Traffic light colors can be picked out, but Google still needs to work on developing cameras that can read them even they're backlit with bright sunlight.

Some of the road situations human drivers would handle without breaking a sweat would also be overlooked by or confusing to Google's systems. Neither heavy rain nor snow conditions have been explored, Urmson admits, and the cars haven't been taken into large parking lots or trained to navigate multi-story garages.

Even the sight of someone – such as a policeman – waving from the side of the road to pause traffic in an emergency would present an issue, as Google's cars would simply ignore them. Significant pot-holes or uncapped manholes would not be navigated around, as again the autonomous systems don't see them unless they're flagged with cones; on the flip side, neither can they differentiate between a rock and a piece of scrunched up paper, opting to instead swerve around each.

If the situation proves simply too confusing, the car will slow to a crawl so as to avoid any accidents or injuries, Google says.

Urmson argues that some of the lingering issues may remain because Google's engineers haven't tackled them yet, which certainly makes sense given what's believed to be a relatively small team in the Google X lab working on the autonomous vehicles. However, there's a significantly more pressing problem that's going to require far more manpower.

While the cars obviously have sensors – including the distinctive LIDAR tower mounted on the top – to keep them abreast of road conditions, the core navigation is all done in advance. Routes are programmed based on data-rich maps many degrees more complex than what you see on Google Maps, for instance, and that level of cartography is in relatively short supply.

As well as junctions, such maps contain information on how many lanes are present, where signs and signals are placed, and more, with Google saying it takes "multiple passes" with a special vehicle before its teams have enough data to compile them with sufficient accuracy.

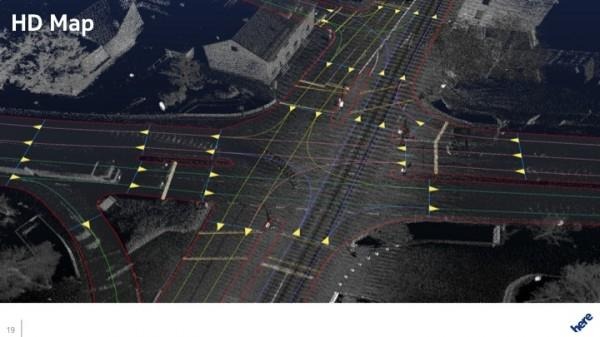

It's not the first time we've heard such comments. Nokia's HERE division, which recently cut a deal with Samsung to bench Google Maps, has been gathering what it calls "HD Map" data for some time now; when we visited the HERE team back in April, they described how elements even down to curb presence and height, lane width, and elevation are taken into account, all with the goal of giving self-driving cars sufficient understanding to coexist with human drivers.

HERE uses a fleet of mapping vehicles equipped with high-resolution cameras, LIDAR scanners, and other sensors to build up three-dimensional point maps of the environment. However, it also envisages car-to-car communication being increasingly important to give driverless cars a glimpse of what's coming around the corner, telegraphed back from traffic further down the road.

"The best sensors will give you maybe 100-150 yards," HERE VP of Connected Driving Ogi Redzic explained to SlashGear. "If you're going at highway speeds, it's not going to be good at 200kph on the Autobahn, it means you can only see so much. You have to know what's coming up next as well."

HERE won't be building its own autonomous cars, but does supply mapping data to many car companies. It has also argued that, rather than trying to drive "perfectly", self-driving vehicles should mimic human patterns to encourage adoption.

It's unclear how long Google expects it to take to sufficiently map US roads so that its pods can be deployed more widely. According to Urmson, those cars which spot an unexpected sign or other change to the highway will flag it up so that Google knows to update its data.

Urmson is confident that Google will be able to address the lingering issues sooner rather than later, though isn't giving a firm timescale on when we might see commercial versions debut.

Much of that will depend on the slowly evolving regulatory environment, with the NHTSA currently considering where the technology fits into existing road use. Perhaps in Google's favor, that's not likely to be settled any time soon, leading to plenty of time to iron out all the remaining glitches.