What's The Difference Between Ford's 427, 428, And 429 Engines?

Ford's big block engines are among the best-known and most respected V8s in American history. From the pure-blooded racing heritage of the 427 and its derivatives to the massive torque-happy 429 in the eponymous Mustang Boss 429, each engine has its own niche and characteristics that set it apart.

The three Ford big blocks are built and implemented with distinct purposes, each with its own strengths and weaknesses. Much like other big blocks from the rest of the Big Three — GM, Chrysler — they typically occupied one of two vehicle classes: muscle cars and utility trucks, though we'll be focusing primarily on the former. Regardless of which engine we're referring to specifically, all the big blocks featured here were beefy, torquey monsters that defined the cars they were housed in.

There are various specialized models of each of these engines. The 427, for instance, was available in several different configurations, from the "basic" models to the SOHC full-on racing blocks, each with its own distinct provenance. We'll review all the major configurations of each powerplant, discussing key differences apart from the superficial number and models they were in, beginning with the legendary "FE" big blocks.

427 FE - the fire-breather

NASCAR underwent a massive arms race throughout the early to mid-1960s, with each of the major manufacturers throwing everything they had to make their cars faster. "Win on Sunday, sell on Monday" was the order of the day, doubly so because this was an era when NASCAR stock cars were quite close to the vehicles you could buy. And the 427 FE (meaning Ford Engine, not Ford Edsel) marked Ford's entry into this realm, directly competing with the likes of the 426 Hemi and GM's 409 (later their own 427) on the circuit and drag strip.

As a street block, the 427 replaced the long-lived Y-block V8, upgrading much of its parent engine's internals. It features a bore of 4.232 inches and a stroke of 3.784 inches, making its actual volume 425.82 cubic-inches. The many updates from the older Y-block include hydraulic lifters to replace the solid lifters, a redesigned valvetrain, and higher bore spacing (the distance between two cylinders), allowing for more material in the block, and thus more potential for big, reliable power.

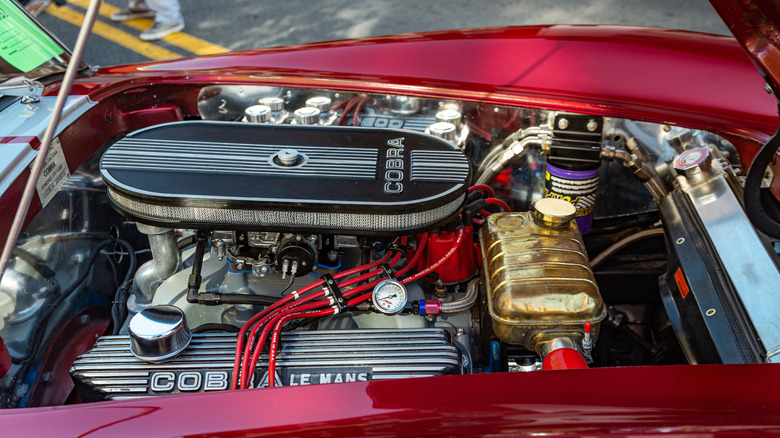

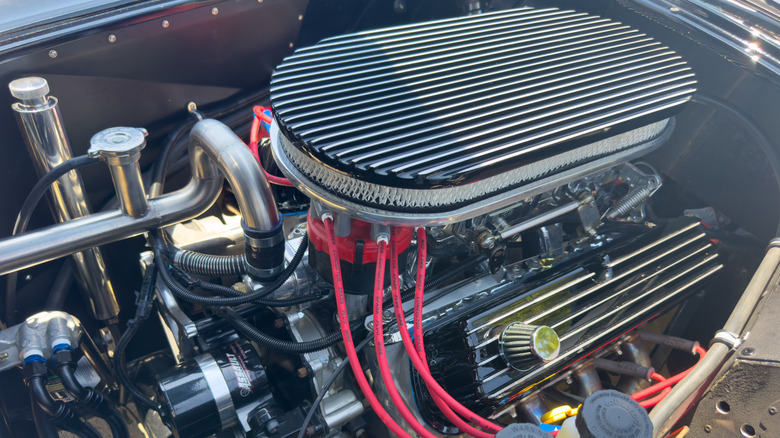

The 427 FE is one of the best-known racing engines of all time, appearing in various high-profile machines such as the "side oiler" 427-equipped Shelby Cobras and the Mark II Ford GT40. They were serious engines with wildly fluctuating power numbers. Even the base model 427 produced some of the highest power figures around, with cars like the 1967 Ford Fairlane Thunderbolt featuring one of two 427 trims — either the standard 427 with a single 4-barrel carburetor rated to 410 horsepower, or the dual-carb variant hitting 425 horsepower, the same figure as the Hemi.

427 SOHC Cammer - the 90-Day Wonder

Designed in 90 days, the SOHC 427 was known by a few names, including "Cammer", "Sock," and "the 90 Day Wonder." Ultimately, this engine was merely a two-valve, single overhead-cam factory conversion of the standard 427 FE, which was normally a traditional pushrod overhead-valve configuration. However, in practice, the Cammer was an entirely different beast, built to withstand the high RPMs of high-speed stock car racing at superspeedways.

Unlike the standard 427 FE, the Cammer was a largely bespoke racing engine using the side-oiler block, so named because of the oil gallery located to the side of the crankshaft for better lubrication under stress. These were the endurance racing engines you'd typically find in Le Mans cars, circuit racers, and so on. The Cammer simply took that formula and doubled down for prolonged high-speed driving. However, the 90 Day Wonder had a few odd idiosyncrasies, such as a 7-foot timing chain that required drivers to tune the car accordingly because of slack in the chain. Moreover, because it was a single chain, it drove both cams in the same direction, meaning each cam needed to be a mirror image of the other to compensate.

While rushed in development and less than ideal in terms of its internals, the Cammer nevertheless left a lasting impression on the motorsports and muscle car community, becoming infamous once NASCAR banned the engines in 1964, lifted the ban, then banned it again in 1965. The Cammer earned a reputation for being one of Ford's most potent big blocks ever, and rightfully so.

428 FE - the streetable torque monster

With a bore of 4.13 inches and stroke of 3.98 inches, the 428 marked the largest of the FE big block configurations available from the factory. Unlike the 427, however, the 428 FE was tuned more for low-end grunt for Ford's full-size cars from 1966 onward, with one highlight being the Galaxie. It was produced largely alongside the 427, with that engine dominating the motorsports end of Ford's development until 1970. This freed up the 428 to appeal to a more mass-market demographic, with the torque being particularly useful for long-distance cruises more than outright performance.

In short, the standard "Thunderbird" 428 FE was the most ubiquitous and mild-mannered of all the big blocks, featuring a single four-barrel carburetor, log-style exhaust manifolds, low-rise intake, mild cam, and a lazy 345 horsepower at 4600 RPM and 462 pound-feet torque at 2800 RPM. It could certainly get out of its own way, but it was more designed to comfortably cruise up the hills of San Francisco than it was as a fast engine. Nevertheless, the standard 428 was quite capable, even becoming a police interceptor block with a higher-lift camshaft, bringing power figures up to 360 horsepower and 459 pound-feet of torque, respectively.

Being more pedestrian engines, the internal makeup of the 428 FE is instantly recognizable to anyone who knows their way around these sorts of units. In addition to the standard exhaust and valvetrain configurations, these engines featured a cast-iron crankshaft mounting forged-steel conrods, alongside a 2.04" cast-iron intake. Hardly speed demons, but they were durable, simple, and excellent daily drivers.

428 Cobra Jet

While the standard 428 might've been an engine designed for casual highway cruising, the Cobra Jet and Super Cobra Jet were far more performance-oriented, though not to the extent of the 427. While sharing the "428" designation, the Cobra Jet actually featured a number of key differences that made it a more potent racing engine, primarily destined for NHRA drag racing. First offered in 1968, the 428 CJ boasted various design cues from other prior FE designs, such as the 427's Low Riser heads, the 390 Police Interceptor's intake manifold, and different main bearing webbing versus the standard block.

All these and more added up to a robust muscle car engine on equal footing to the GM and Chrysler big blocks of the era. And it was, principally, a muscle car engine, most famously seen in the 428 CJ-powered 1968 Shelby GT500. In fact, the 428 engine has been in the GT500 since 1967, in the guise of the 428 Police Interceptor package. Since then, the evolved Cobra Jet was installed on all the standard Ford muscle cars of the era, especially the 1968-1970 Mustangs.

Ironically, however, the factory power rating of the Cobra Jet was lower than the standard 428 FE, boasting just 335 horsepower at 5200 RPM and 440 pound-feet of torque at 3400 RPM. In fact, power figures seem to be all over the place, with the 1969 Shelby GT500 advertising that same power at just 3200 RPM, 200 RPM less than the advertised torque figure. Whether it's a typo or Ford deliberately underrating is a matter of debate; what isn't is the performance characteristics. Cars housing the 428 Cobra Jet were typically fast, svelte sports coupes, offering a compelling performance alternative for muscle enthusiasts.

429: The Boss

Unlike previous engines on this list, the 429 was not an FE engine; rather, it's the progeny of the 385 big block. Produced in one form or another for a whopping 30 years (1968 to 1998), this is also by far Ford's most prolific big block, though the ones we'll concern ourselves with here are the pre-Oil Crisis engines produced to 1973. These include the venerable 429 Cobra Jet as seen across various muscle cars, along with the infamous Boss 429 featured in the eponymous Mustang. The Boss engine was Ford's answer to Chrysler's Hemi-powered NASCAR dominance in the late 1960s.

The 429 debuted in the 1968 Ford Thunderbird, initially marketed towards two crowds: high-end luxury and performance-oriented vehicles. As a replacement for the short-lived FE, it featured similar levels of durability and power characteristics, with the top-tier Boss 429 arguably being underrated with 375 horsepower (in reality, the thing was a street variant of a NASCAR homologation engine). Also, much like the 427, the 429 featured a shorter stroke in relation to its bore size, with a 4.36-inch bore and 3.69-inch stroke. This helped optimize the engine for higher-RPM work, crucial on superspeedways and other high-speed applications.

Due to the significantly varied nature of the engines and their uses, various internal specs differed; compression ratios, for example, varied between 8.5:1 and 10.5:1 in the Boss (alongside the Super Cobra Jet, among other configurations). However, their versatility, coupled with their performance pedigree, solidified the 429 as one of the greatest big block V8s, period.