China Beamed Gigabit Internet From Space Using Low-Power Lasers: Here's How It Worked

China is currently giving tough competition to Western tech giants, especially in frontier innovation segments such as electric cars, AI development, and energy transition. It appears that Starlink, the global leader in satellite-based connectivity, will soon have tough competition from China, as well. A team of Chinese researchers has now demonstrated a "groundbreaking" satellite-based connectivity system that reached a peak speed of 1 Gbps for data using extremely low power lasers.

The system developed by Chinese scientists relies on a new type of wireless link infrastructure called AO-MDR synergy, according to a report by the South China Morning Post. But it was not just the sheer speed that set this achievement apart. The team achieved the feat using a 2-watt laser system. For comparison, a study published in the IEEE Vehicular Technology Magazine puts the laser transmit power of Starlink satellites at 10W and Ka-band radio transmission to Earth at 50W.

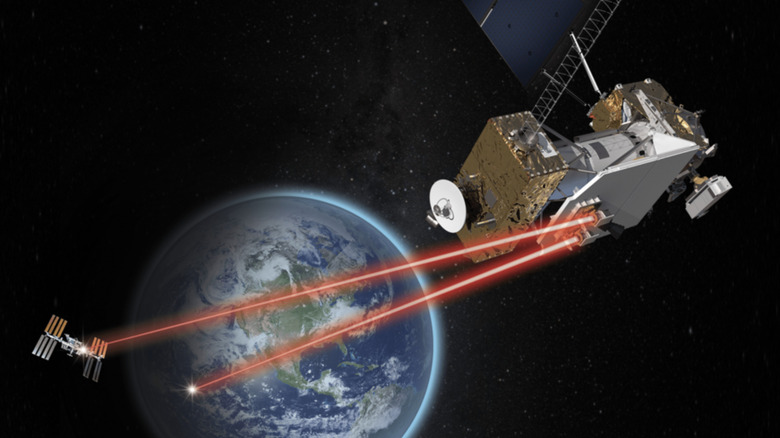

Starlink satellites come equipped with optical space lasers, delivering a staggering 200 Gbps output. But these laser links are used for connection between the satellites, and are not beamed to the receiver terminal on Earth.

The secret sauce

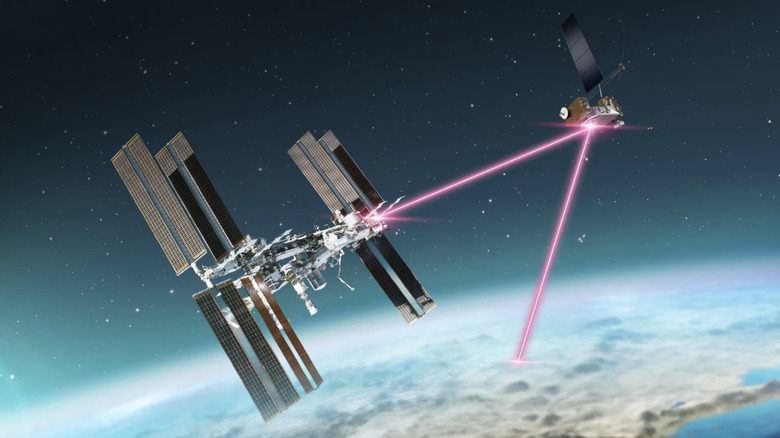

The project is a brainchild of experts from China's Peking University of Posts and Telecommunications and the Chinese Academy of Sciences. The transmission was received using a 1.8-meter (5.9 foott) telescope that features 357 micro-mirrors to concentrate the laser signal from the satellite. But why laser? Laser communication is increasingly being seen as the future, as it allows dramatically more data to be transmitted with a single link compared to radio-based systems.

Just over a year ago, NASA demonstrated the TBIRD (TeraByte InfraRed Delivery), which achieved a data transmission rate of 200 Gbps in a single pass. Chinese scientists relied on a similar laser transmission approach to achieve 1 Gbps output. Notably, a commercial satellite company in China has already demonstrated satellite-to-ground laser communication that achieved a staggering 100 Gbps transmission rate.

Atmospheric disturbances such as rain, smog, and particulate matter remain the biggest challenge for laser-based connectivity, as they degrade signal quality and reduce reliability. Despite this, the Chinese team managed to maintain a 1 Gbps satellite link even through turbulent skies. Their latest effort used a multi-plane converter that split the laser signal into eight base-mode channels. On the ground, three of those signals were selected and merged using custom chips. This method increased the chances of collecting usable signals from 72% to more than 91%, improving both reliability and overall speed.

A similar feat involving laser-based ground-satellite communication was achieved by Japanese scientists earlier this year. A team of experts, including folks affiliated with the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA), demonstrated an error correction code system that solves the problem of signal fading in laser signals due to atmospheric turbulence. These breakthroughs signal that laser communication is the next evolution of satellite-based communication, as the solutions to a fundamental problem have been successfully demonstrated.

Avoiding an astronomy problem

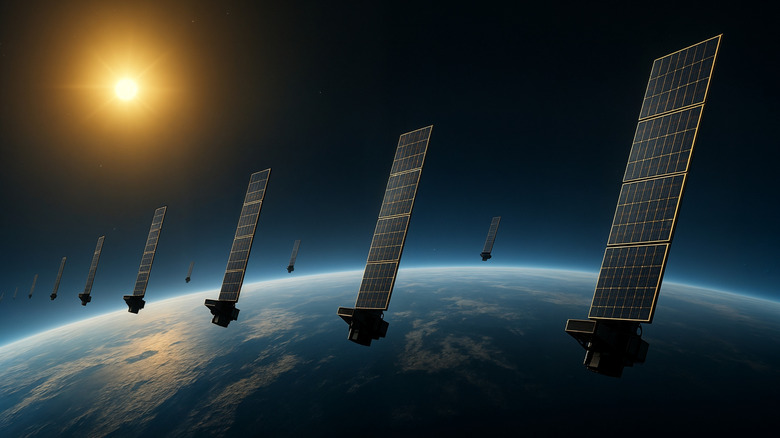

The latest breakthrough in satellite communication by Chinese scientists managed to achieve next-gen transmission speeds while solving the crucial signal loss problem. But in hindsight, it also avoids a problem that has been hotly debated in the scientific community — the satellite congestion in Earth's orbit. The experimental laser-transmitting satellite used in the demonstration is parked at a much further position than a Starlink unit.

Starlink satellites float in low-Earth orbit at an altitude of 550 kilometers (roughly 341 miles), while the satellite deployed by the Chinese team is positioned at a distance of 36,705 kilometers (22,807 miles) from the receiver telescope. Simply put, it's positioned in a far less congested space, and even if the number of such satellites goes up, it won't be as crowded as the low-Earth orbit.

Astrophysicists have repeatedly highlighted the problem of light pollution caused by the increasing number of low-Earth orbit satellites and how it could ruin radio astronomy. The optical interference from satellites, such as light streaks and flares, is a well-known problem. But the new-age satellites, such as Starlink, are also leading to radio interference. In a recent analysis, experts at the Paris Observatory and the Nançay Radio Astronomy Observatory highlighted the issue of "very intense out-of-band emissions" from Starlink satellites.

There's already one satellite per square degree of the observable sky, and it's causing. As the likes of SpaceX and Amazon's Project Kuiper deploy thousands of new satellites in the near future, the problem is going to worsen. And let's not forget their role in exacerbating the disaster-prone space debris problem. Laser-based satellites that are higher (and further) in the orbit could emerge as a faster, more efficient, and astronomy-friendly option. It remains to be seen whether Chinese firms can beat SpaceX at commercializing it.