NASA's Future Without The ISS Involves Commercial Space Stations, But It Will Take Multiple Phases To Get There

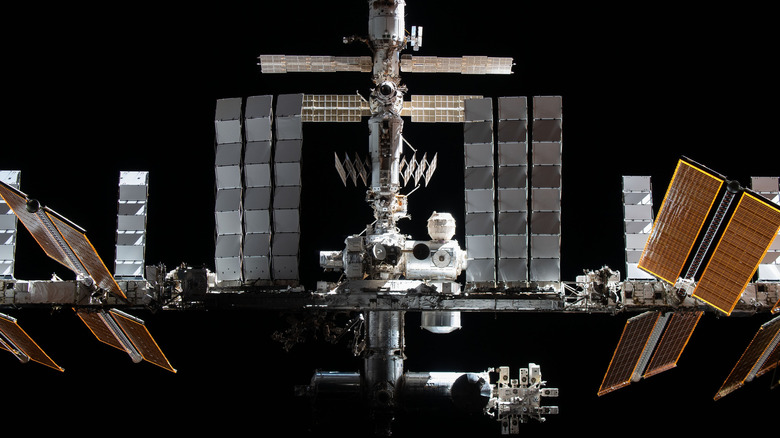

NASA is saying goodbye to one of the most important satellite projects in the history of spaceflight as it moves forward with plans to shutter the International Space Station. Built and launched at the turn of the century, the ISS is the longest continuous astronaut presence in history, keeping an American in space until it deorbits in 2030. Doubling its intended lifespan, the station has been a paragon of international scientific cooperation, hosting roughly 280 visitors across 26 partner countries and delivering insights into astrophysics, biotechnology, astronomy, combustion, earth science, and more. In June 2024, NASA took a major step towards ending this era of space science, awarding SpaceX the $843 million contract to deliver the ISS into the Earth's atmosphere and crash it into the Pacific Ocean.

NASA plans to replace the station with commercial space stations from which the U.S. can purchase mission space. A new directive issued by NASA Administrator Sean Duffy offers a fresh glimpse into this transition, reworking the three-phase development process that will see companies compete for roughly $1 billion and $1.5 billion in new funding to develop, build, and demonstrate commercial space stations between 2026 and 2031. NASA is entering the second phase of the initiative.

Part of a broader reorganization of NASA's acquisition program, the agency hopes that privatizing space stations will lower the costs of low Earth orbit (LEO) operations, enabling it to shift resources to "the next step in humanity's exploration of the solar system." Some note that the decision will carry scientific and geopolitical consequences in the escalating space race between global powers.

Launching a commercial space station

NASA is currently at the starting line of the second stage of its three-phase transition to commercial space stations. Phase 1, begun in 2020, saw NASA sign several agreements with companies to design commercial space stations. The list of participating organizations includes Axiom Space, Blue Origin, Northrop Grumman, Starlab, Sierra Space, Special Aerospace Service, ThinkOrbital, Vast, and SpaceX. In addition to monetary support, NASA provided technical expertise, training, and technological assistance.

In September 2025, NASA released its first draft of the Phase Two Announcement For Partnership Proposals (AFPP), in which companies will receive funding to orchestrate design reviews. Funding will be provided through Space Act Agreements, replacing a fixed-price contract system and allowing for greater flexibility as companies attempt to synergize NASA requirements and individual business interests. The phase will include demonstrations of four astronaut stations in LOE for 30 days. Currently, NASA is accepting industry feedback on its AFPP, with a final draft expected to come in October 2025. Proposals are expected to have a December 1, 2025, deadline, with awards to be handed out in April 2026. NASA hopes to hand out at least two development contracts worth up to a collective $1.5 billion for 2026 to 2031.

The final phase will see NASA undergo a formal design acceptance and certification process to ensure commercial space stations meet NASA's strict safety requirements. The agency will then begin purchasing station services through purchase station services through a "full and open competition," using Federal Acquisition Regulation-based contracts. More details will be released regarding Phase 3 in December 2025.

A new space race

For its supporters, the privatization of space merely extends an operational model that saw NASA increasingly depend on commercial partners to deliver goods and services to the ISS. The logic behind space station privatization parallels that of other privatization projects: lower costs, higher efficiency, and greater competition (hopefully) breed more innovation on the cheap. The recent success of private space companies, along with NASA's previous private partnerships on SpaceX's Dragon and Boeing's Starliner spacecraft, attests to the potential of commercial space stations.

But some worry that these gains will come at a hefty geopolitical price, noting that losing America's permanent LEO presence could create a void that China's dual-purpose space program can fill. For instance, Beijing will continue to operate its Tiangong space station, a three-person facility that will become the longest active permanently crewed space station once the ISS deorbits. China hopes to launch its International Lunar Research Station by 2035. A collaborative project with Russia, Beijing has added 17 nations and 50 research institutions to its ILRS project, planning to extend the project into a 50-nation consortium that serves as the preeminent vehicle for international space cooperation.

The success of these competing space station models will have a major impact on a burgeoning space race with scientific, military, and geopolitical implications. Global powers like the U.S., China, and Russia are increasingly looking to space for military, energy, and technological advantages, ranging from missile defense architecture to lunar nuclear reactors. What effect NASA's shift to commercial space stations will have in this duel of competing space ambitions remains to be seen. However, one thing is certain: the final frontier will take center stage in this next era of global geopolitics.