Oldsmobile F-85 Jetfire: The Bizarre Engine That Was Ahead Of Its Time

The Oldsmobile Jetfire represented one of the relatively lesser-known pioneers of turbocharging, something we take for granted on everything from econoboxes to high-speed dedicated race cars. In fact, it was the first ever turbocharged production car; debuting in April 1962, and beating Chevrolet's Corvair Spyder to the punch. These days turbocharging technology is a well-understood science, with modern turbos capable of producing good, reliable power while maintaining fuel-efficiency without giving the owner any grief. Back in the early-60s, though, it was a far different story.

The Oldsmobile Jetfire was a car ahead of its time, if ever there was one. There's always a first for everything, and while turbochargers had existed for decades at that point, they'd never found their way into engine bays of economy cars. Turbochargers were designed principally for consistent, lower-revving engines like those found on aircraft, and faced numerous challenges implementing them into cars in those early days. For example, early turbochargers demonstrated significant turbo lag, owing to the lower compression ratios used to mitigate knock that lowered an engine's low-end power. How did the Jetfire solve that problem?

Well, considering just 9,607 examples were produced from 1962-1963, the Jetfire solved it rather poorly, but that's to be expected of such an early design. Its engine used a specialized liquid-injection mechanism, coupled with a high 10.25:1 compression to help mitigate the effects of turbo lag. So why was this system so poorly received?

How the Oldsmobile Jetfire's turbocharger works

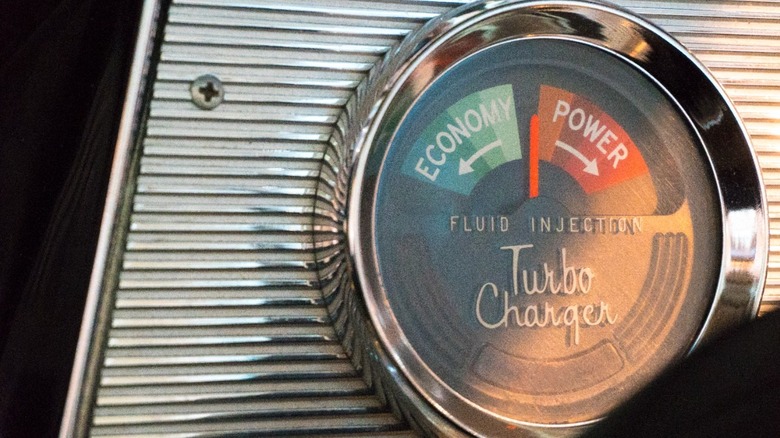

The Oldsmobile Jetfire was one of the few cars of its era with one horsepower per cubic inch, boasting 215 horsepower from a 215 cubic-inch V8 coupled to either a standard three-speed column-shift, or an optional four-speed manual or Hydramatic transmission. It represented the top-of-the-line of the F-85 model family: For all intents and purposes, it was a true hardtop variant of the Cutlass, featuring the same running-gear and handling characteristics. Those differences end at the engine, with the Jetfire foregoing the typical single four-barrel carburetor for a side-draft carburetor with the turbo mounted on top.

Internally, the engine featured several heavy-duty components such as pistons, main bearings, and intake valves. As for the turbo itself, the Jetfire utilizes a Garrett AiResearch T-5 turbocharger, which increased the normally 185-horsepower V8 up to 215 horsepower. Boost was limited to a pedestrian 5 PSI, though it was enough to provide the Jetfire with a respectable 300 lb-ft of torque.

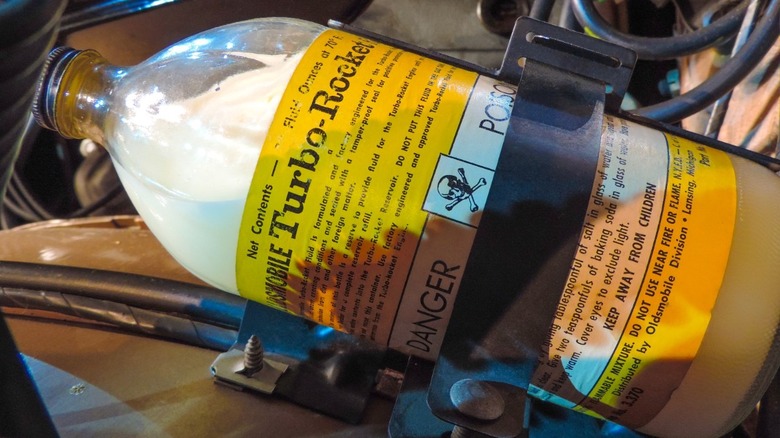

Now for the weirdness, namely with the liquid-injection system: The Jetfire contains an additional reservoir filled with a mixture of 50% water, 50% methyl alcohol, along with a dash of rust inhibitor to keep the fluid from corroding the rubber hoses. The Jetfire's system sprayed this fluid, which GM called "Turbo Rocket Fluid," into the air-fuel mixture to help cool the engine's internals; a byproduct of the car running such a high compression ratio. This required owners to periodically top up the fluid, otherwise the system would limit itself to avoid engine damage until the tank was replenished. There have been few vehicles to utilize such a system since, with an example being the BMW M4 GTS, one of the fastest BMWs by top speed.

What was the problem with the Jetfire?

First-off, let's consider how many people neglect to get an oil change at the prescribed interval. Now imagine introducing an entirely-new fluid into the mix, one which is totally unfamiliar to the average customer. This simple fact led many owners back to dealers with a variety of complaints about the engine's reliability, when in reality, many had simply neglected to fill the tank. GM put out a series of brochures and advertisements that explained the turbocharger system in-depth, but even so, the engine faced numerous other problems aside from "rocket fluid"-related neglect.

For example, if you ran the turbocharger and immediately parked the car, the system would remain pressurized, potentially causing a fluid buildup in the cylinders and immediately hydro-locking the engine when restarting the car. The fluid itself was corrosive, and made the robber hoses brittle. The entire system was mechanical, and had a variety of faults such as leak-prone seals, an oil pump that generated insufficient pressure, and more. Owners were so disgruntled that GM first offered a pressure-relief valve fix before finally acquiescing and accepting returns, exchanging the Jetfire's turbo for a traditional 4-barrel carburetor. About 80% of Jetfires had this service performed, by one estimate.

This was a highly-experimental system with numerous teething problems, introduced to a customer-base which was, generally-speaking, totally unfamiliar with how to properly maintain and drive a turbocharged car. This created a cascading effect which resulted in large-scale rejections and recalls, souring American public opinion of turbos until the Oil Crisis. While unquestionably an engineering curiosity, the Jetfire was ultimately assembled at the wrong point in automotive history, and perished just as quickly.