Why Don't Cars In England Drive On The Right Side Of The Road?

When it comes to roads, driving, and automobiles, the English tend to do things a little differently to Americans. In Old Blighty, trucks are called "lorries", drivers turn using indicators instead of blinkers, and crosswalks are called "zebra crossings", even though you rarely see a zebra using one. More importantly, especially if you happen to be driving over there, you will find the English insist on driving on the wrong side of the road.

Of course, the Brits would argue they drive on the correct side of the road — the left-hand side, according to the law. Driving on the left requires that their road vehicles be right-hand-drive, so the driver is seated closer to the center line than to the sidewalk (and shifts the stick with the left hand). A right-hand-drive car on the left side of the road gives the driver a better view of oncoming traffic — very handy when overtaking or making a right-hand turn.

But when cars in 65% of countries in the world are driven on the right, including across most of continental Europe, why are vehicles in the U.K. driven on the left? While this could be put down to bulldog-like obstinacy, the reason, as it turns out, is mostly because of Napoleon.

Road rules were driven by conflict

In the 17th century, British writer Thomas Hobbes described life as "nasty, brutish, and short", arguing people were driven by fear of death and a desire to get ahead – twin motives we see playing out on the highways today. In feudal times, horse riders tended to travel the roads on the left, with most people's dominant right hand, the sword hand, ready to fend off potential attackers coming down the road on the right. Britain consolidated this into a road rule in 1835, but not before France and the U.S. chose to do the exact opposite.

In France and the early U.S. of the late 1700s, teams of horses began hauling goods over long distances. Teamsters rode on the rearmost horse to the left, leaving their right arm free to lash the pairs of horses ahead. As with drivers today, they sat nearest the centre of the road, driving on the right. France made this unwritten road rule official in 1794, after similar moves by Denmark and Russia.

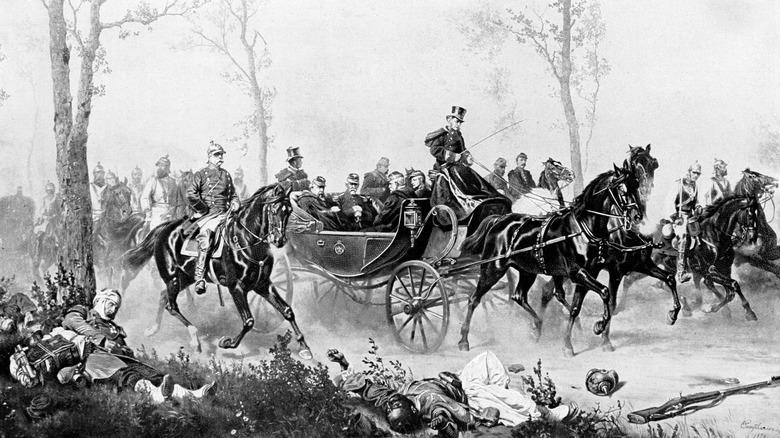

The expansionist Napoleonic Wars of the early 1800s laid down this law across whole swathes of Europe, including Germany, Italy, and Poland, arguably because the left-handed Bonaparte also preferred to travel on the right. As horse-drawn carriages called "spiders" began traversing European cities, they followed the same rules, which would eventually come to apply to the horseless carriages of the 20th century. Meanwhile, countries that had resisted Napoleon, including Britain, continued down the left-hand side of the road.

When in Rome, do as the Romans do -- even if not all roads lead you there

Continental Europe was fully right-sided by the 1960s, after the last hold-out, Sweden, switched in 1967. When crossing between England and continental Europe, vehicles were carried by ferry, and later by train through the Channel Tunnel, with drivers avoiding the confusion of switching sides while behind the wheel. Provinces in Canada all switched to the right by 1947, with free-for-all border crossings becoming a thing of the past.

Former British colonies like Australia, New Zealand, India, and countries in southern Africa, also favor the opposite side of the road to the U.S., as does Japan — but interestingly, that is not why imported American vehicles aren't popular there. The reason instead has everything to do with culture, and little to do with any idea of a universal norm.

When traveling or driving in a foreign country, it pays to learn about cultural differences, as well as the rules of the road. A mistake on the road is not just an embarrassing faux pas — it can lead to injury or death. If you intend to drive overseas, take a refresher course to improve your spatial awareness, and learn to drive stick, as auto-transmission rentals aren't always available. Find out what laws apply before leaving, and on arrival, take a few trips as a passenger first, to study the local traffic.