The History Of Virtual Reality: How VR Has Changed The Way We Know Gaming

The best video games carry a feeling of immersion, as though players are being actively transported into the world of the game. Virtual reality takes that immersion to the next level. Players truly see the world through the eyes of an in-game avatar and can interact with the world in a way that is impossible (or at least impractical) in a regular video game played on the television. Modern VR headsets provide stereoscopic 3D visuals with head and eye tracking technology, motion-sensitive controllers that allows players to see your character's hands in real time, and other functions that bridge the gap between the gamer and the game.

Until 2016 or so, VR was largely seen as a relic of the totally radical Cyberpunk craze of the 1990s. In 2025, VR still hasn't been widely adopted by the mainstream gaming audience, but it's definitely carved out a niche for itself with players who appreciate an experience that simply can't be replicated in traditional video games. Virtual reality gaming might not be world-changing (yet), but the technology has grown from fantastical fiction to flesh-and-blood fact and beyond. Let's take a look back and explore the history of VR.

Science fiction origins

When it comes to technology, before something can become science fact, it must first navigate the realm of science fiction. Virtual reality is no different. "Pygmalion's Spectacles," a 1935 short story by Stanley Grauman Weinbaum, involves a man who wears goggles that effectively transport him into a virtual reality simulation. In the story, the technology's creator says that potential investors dismissed his technological marvel because it was too expensive, a complaint that's still levied at real virtual reality equipment to this day.

Meanwhile, Ray Bradbury's 1950 short story, "The Veldt," follows a family of four living in a fully-automated smart house decades before the term was invented. The house features a virtual reality room called 'The Nursery,' to which the children of the house become addicted, roughly 65 years before the Baby Shark YouTube channel racked up billions of views on YouTube.

Fast forward to the 1980s and you have the Holodeck from "Star Trek: The Next Generation" (though the Holodeck concept appeared earlier, in "Star Trek: The Animated Series"), a fully immersive, glasses-free virtual reality simulation that's indistinguishable from real life. It feels like the logical endgame for modern VR applications is to create a Holodeck-like experience, but it will likely be quite a few decades or more before that science-fiction concept becomes fully realized in real life.

Early applications

The earliest VR experiences weren't for gaming, or really any kind of recreation, but for training simulators. The photo above is of NASA's Cockpit Motion Facility, or CMF. The motion-based simulator, built in 1976, can rock and shake like a real aircraft or space shuttle, allowing astronauts to train with maximum immersion. Several years earlier, in 1972, General Electric built the first VR flight simulator for more terrestrial aircraft pilots, giving would-be pilots more effective training before they would actually take to the skies.

When it comes to head-mounted displays, the very first prototype was built in 1968 by Dr. Ivan Sutherland, a luminary in the field of computer programming and the early days of 3D graphics. Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, technologies like wired gloves and motion-tracking head-mounted units were developed and adopted for use by NASA, the military, and other high-tech institutions. The devices became more advanced, and the idea of virtual reality in the home began to gain traction, not just as a possibility, but as an inevitability.

The cyberpunk era

Though science fiction has been around for as long as the concepts of science and fiction, the term cyberpunk wasn't coined until the release of the 1983 short story, "Cyberpunk," by Bruce Bethke. As the genre evolved, the idea of humans harnessing the power of computer technology naturally led to virtual reality simulations being a mainstay of the genre. The works of William Gibson, Neal Stephenson, and other science-fiction authors heavily influenced the perception of computer culture and the possibilities presented by cyberspace.

The image above comes from the 1992 film, "The Lawnmower Man," in which a mentally challenged man (Jeff Fahey) is given VR and drug treatments to unlock his mind's potential. Without spoiling anything, it's a fantastic, if dated, sci-fi thriller that uses cutting-edge (for the time) CGI effects to depict VR worlds within cyberspace. The effects might not hold up to today's standards on a technical level, but within the universe presented by the film, they preserve the otherworldliness of its VR sequences.

Too much, too soon

Alas, while movies like "The Lawnmower Man" made virtual reality seem like an imminent development, the real world wasn't so technologically advanced. The initial wave of VR hubbub brought about by science fiction sputtered out in the '90s after a series of high-profile VR failures, most notably Nintendo's Virtual Boy. The device lacked any kind of motion tracking and the display wasn't even head-mounted. Players had to push their face against the unit, like those coin-operated telescopes in New Jersey's Liberty State Park that point towards the Statue of Liberty. While capable of stereoscopic 3D visuals, the Virtual Boy was woefully under-powered and could only display images in garish shades of red and black.

Other high-profile VR duds of the 1990s included Virtual IO's I-Glasses, Sega's Virtuality, and the VR-1, also by Sega. The VR-1 was considered to be exceptionally well-made for its time and was praised at the various Sega theme parks at which units were installed, but as Sega's theme park ambitions fizzled out, so too did the VR-1. There were planned VR add-ons for the Sega Genesis and Atari Jaguar, but they were both quietly cancelled.

Nintendo Wii/PlayStation Move/Xbox Kinect

Virtual reality all but disappeared after the turn of the millennium, reserved for science fiction or to laugh at its 1990s heyday that never was. However, technology would soon emerge that would, unbeknownst to the masses, become integral to the next generation of VR.

In 2006, Nintendo launched the Wii home console, and it became a full-on phenomenon. The mass appeal of the Wii came down to two factors: first was its price point. At $250, it was less than half the price of the PlayStation 3's infamous $599. Cheaper even than the Xbox 360, which launched at $300. The second factor was its main hook: simple-to-use motion controls that almost anyone could understand. Casual games like "Wii Sports" and "Just Dance" took the world by storm and were enjoyed by kids, parents, and grandparents alike.

Seeking to ride the wave of the Wii's success, Sony and Microsoft sought to add Wii-like motion controls to consoles. Sony's response was the PlayStation Move, an obvious copycat of Wii's motion controllers that wound up paying off in a surprising way in during the PS4 era (but more on that later). Meanwhile, Microsoft created Kinect, a hands-free motion control solution for Xbox 360 that managed to differentiate itself from the Wii.

Oculus Rift

The father of VR in its modern form is Palmer Luckey, co-founder of Oculus VR. In 2012, His company launched a Kickstarter campaign to support the development of Oculus Rift dev kits, promising VR technology that was better than ever, and relatively inexpensive compared to the VR units used by NASA, the military, and other large entities. The Kickstarter's success caught the attention of gaming luminaries like John Carmack and Gabe Newell, who praised the company for its work, signifying that VR was, indeed, on the cusp of a grand comeback.

As development on the Oculus Rift continued into 2013 and beyond, other companies realized the untapped potential of VR and threw hats in the ring. By the end of the decade, HTC, Valve, Google, Sony PlayStation, and more would each have its own VR platforms. Heck, even Nintendo got in on the action with its cardboard Nintendo LABO papercraft device, though that was more of a novelty than a genuine VR platform.

Facebook buys Oculus

With all these players suddenly in the VR space, it was only natural that some would inevitably devour each other. Still, few could have predicted that Facebook would spend $2 billion to purchase Oculus VR in 2014, before they had even produced a commercial product. While the first Oculus product finally shipped in 2016, the brand name was phased out over the next several years, overtaken by Facebook's Meta branding. Ever wonder why there's a Meta Quest 2 and 3, but no Meta Quest 1? It's because the Oculus Quest 2 was renamed Meta Quest 2 in 2022, 2 years after its initial release. There was never a product named Meta Quest 1, but the original Oculus Quest from 2019 was essentially the original version of the Meta Quest as we now know it.

Presumably, Facebook's deep pockets were used to secure deals for VR games from big franchises like Assassin's Creed, Batman Arkham, the upcoming Deadpool VR, and even a 2021 VR version of Resident Evil 4 — the original RE4, not the 2023 remake, which got its own VR mode as a PlayStation VR2 exclusive. The fact that there are two VR versions of Resident Evil 4 exclusive to different platforms suggests that fierce competition persists in the VR space.

PlayStation VR

With the new VR revolution in full swing, it was inevitable that one of the big home console players would utilize the hot new technology to bring games to platforms outside of the typical PC ecosystem. In 2016, Sony took the plunge with PlayStation VR, which leveraged existing technology to save costs, for better or worse.

PSVR utilized a relatively low-spec (1080p, with a 100-degree field of view) headset, but it more than got the job done by 2016 standards. It cleverly utilized the PlayStation 4 camera, which had been available since the console's 2013 launch, and repurposed the PS3-era PlayStation Move controllers for use as VR controllers. It wasn't the most elegant solution, but it was the most accessible and, even with its $400 launch price, affordable VR system of the era. Alas, it did catch some flak for the sometimes-shoddy motion tracking of the PlayStation Move controllers, as well as amount of cables required to get the thing working, including an external box that needed to plug into both the PS4 and the PS VR.

VR arcades

The appeal of VR is self-evident, and the technology is more accessible than ever before, but it's still a pricey hobby, especially for a video game enthusiast. After all, buying a VR headset (and a video game console or PC with which to use it) is one thing, but then buying games is another financial ordeal. For customers who want to try out the tech, but can't afford it, or don't have the space in their apartment to wave their arms around without accidentally smashing a window (or a roommate's face), they can go to a virtual reality arcade.

VR arcades are a lot like classic video game arcades, but instead of video game machine cabinets, each station is a computer with a VR headset, and maybe an attendant to help guide users through the experience. In addition to VR arcades that peddle in commercially available consumer tech, there are also more high-end installations like Sandbox VR that have bespoke VR experiences based on properties like "Rebel Moon" and "Squid Game" that are great for groups of friends to play together.

One of the more high-profile VR businesses was The Void, which sold big-budget VR experiences based on licensed properties. Alas, due to the company's financial troubles, which were exacerbated by the Covid-19 pandemic, all of its locations closed. As a result, VR adventures based on franchises like "Star Wars," "Ghostbusters," "Avengers," "Jumanji," and more are no longer available to play.

Augmented reality

In addition to virtual reality, recent years have also seen the rise of augmented reality (AR), a VR-adjacent technology that uses clear lenses and/or outward-facing cameras to make it look to the user as if images are being projected into the world. The Nintendo 3DS and PlayStation Vita used early AR technology, though it wasn't much more complex than replacing backgrounds with the images captured by the system cameras.

More modern AR variants come in the form of headsets like the Magic Leap, Apple Vision Pro, or other smart glasses, and they allow users to essentially live life with a computer strapped to their face, giving them a heads up display (HUD) like a much dorkier version of Iron Man. Less geared towards gaming than VR, augmented reality tech is more applicable to daily life, allowing users to be online in a way that even smartphones can't provide. It's easy to imagine how AR can help with driving, office jobs, and other tasks that require lots of data management.

The killer app, Half-Life: Alyx

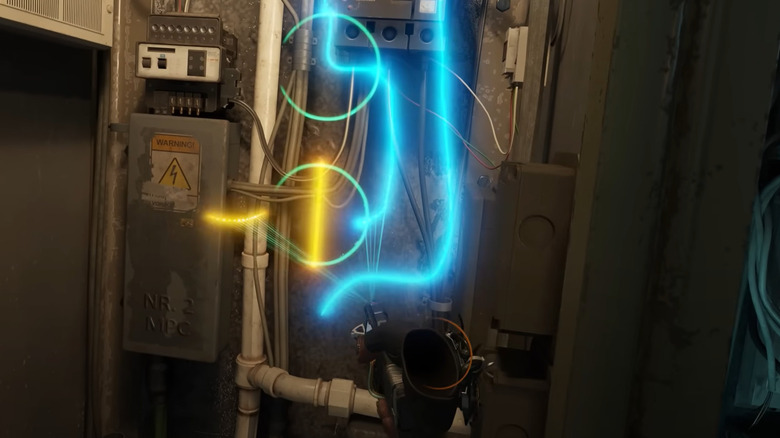

Valve took a little while to enter the VR space, but its 2019 Valve Index headset was seen as top-of-the-line at the time, though it lacked a tie-in game to fully sell the product. That would come 9 months later, in March 2020, with the definitive killer app that single-handedly proved the viability of VR as a gaming platform: "Half-Life Alyx".

Set between the events of "Half-Life" and "Half-Life 2," Alyx is the title character that puts players in the most immersive adventure yet, leveraging the power of VR to allow for unprecedented levels of interactivity, especially for players with controllers that support advanced finger tracking. "Half-Life: Alyx" features plenty of shooting, but also a wide variety of other scenarios that utilize VR in tech-affirming ways.

In addition to its status as a fantastic VR game, Alyx reached beyond the niche VR market due to being the long-awaited return of the "Half-Life" franchise, which had been dormant since 2007. Simply put, "Half-Life" is one of the most celebrated video game properties of all time, so when a new entry is revealed as a VR exclusive experience, even the most ardent tech skeptics have no choice but to take notice. "Half-Life: Alyx" has sold over 2 million copies to date.

The state of VR

In 2023, the PlayStation VR 2 launched with surprisingly little fanfare, despite taking significant strides to move the technology forward. PS VR2 improved on the original PSVR in nearly every way, from its internal camera to bespoke controllers and greatly improved image quality. It launched with a hefty $550 price tag, which is quite expensive, but still competitive in the VR space.

The output of new games on the PS VR2 has been slow and hindered by the lack of backwards compatibility with PS VR games but there are still some standout exclusive titles, like "Horizon: Call of the Mountain" and VR modes for "Resident Evil Village" and "Resident Evil 4 Remake."

Meanwhile, the Meta Quest 3S released in 2024 as an entry-level VR headset that could be used without a wired connection to a PC. The Quest got a boost from bundling units with "Batman: Arkham Shadow". The Meta Quest-exclusive game earned rave reviews and reminded the public that, while VR is still a niche in the wider gaming space, there are top-tier games for those invested in the ecosystem. Likewise, at its June 2025 State of Play presentation, Sony announced several new games for PlayStation VR 2 and other VR headsets, including "Lumines Arise" and "Thief VR: Legacy of Shadow". Overall, while VR gaming isn't the lifeblood of the industry like some may have predicted, it's certainly got a pulse.

The immediate future of VR

Consumers are waiting for the next big step in the VR revolution. Recent headsets like the PlayStation VR 2, Meta Quest 3, and HTC Vive Focus Vision are iterative improvements that build on what came before, though the significance of the wireless functionality featured in the Meta Quest and Vive Focus Vision cannot be overstated.

Valve has been curiously silent on VR since the launch of its Valve Index headset and Half-Life: Alyx in 2020. Valve is infamous for essentially going radio silent for years at a time, but rumors suggest they're hard at work on a new VR headset, codenamed Deckard. If Project Deckard is real, then what could it bring new to the table? Wireless connection to PC seems like a necessity at this point. While VR headsets have gotten smaller and lighter, they're still pretty bulky and uncomfortable to wear for more than an hour or two at a time. One day, maybe VR goggles will be like swimming goggles or fancy sunglasses that can fit in one's jacket pocket, or even contact lenses, but it'll take years for VR tech to reach such an extreme level of portability.

Whatever the case may be, one thing is for sure: if a new Half-Life sequel is tied to whatever Project Deckard turns out to be, we'll find a way to buy it.