What Happened To Standard Oil, The Once-Largest Oil Company In The World

Antitrust lawsuits have shaken up the American economic landscape for over a century. Whether they're going after tech monopolies or breaking up telecom conglomerates, antitrust laws have been a central component of preserving a sense of fairness in America's economy. But followers of Meta and Apple's recent antitrust trials might be surprised to learn that the legacy of the country's current tech monopoly debate is rooted in a similar conversation as that of the oil industry. Roughly 100 years before tech moguls like Mark Zuckerberg, Bill Gates, and Elon Musk dominated the world's economic landscape, a very different kind of industry giant had a claim on the U.S. economy. While the name Rockefeller is now associated with philanthropy and iconic Christmas tree lightings, to older generations, it was synonymous with both the heights of American capitalism and the cutthroat business practices behind it.

The world's first recognized billionaire John D. Rockefeller, ascended to the pinnacle of American success through his conglomerate, Standard Oil, which he grew from a small refinery in Cleveland, Ohio, to the world's largest oil company in less than half a century. At its peak, Standard Oil owned 91% of the U.S. oil market, accumulating a mass of wealth so high that it gave rise to oil's moniker as "black gold." At his peak, Rockefeller's assets were 1.5% of America's total GDP — roughly the same percentage as Elon Musk in 2024.

However, over a century later, America's largest oil empire has seemingly disappeared from the public consciousness. How Standard Oil fell from the pinnacle of America's energy sector harkens back to the earliest days of the U.S. fight against monopolies. It serves as a testament to both the strengths and failings of these legislative priorities.

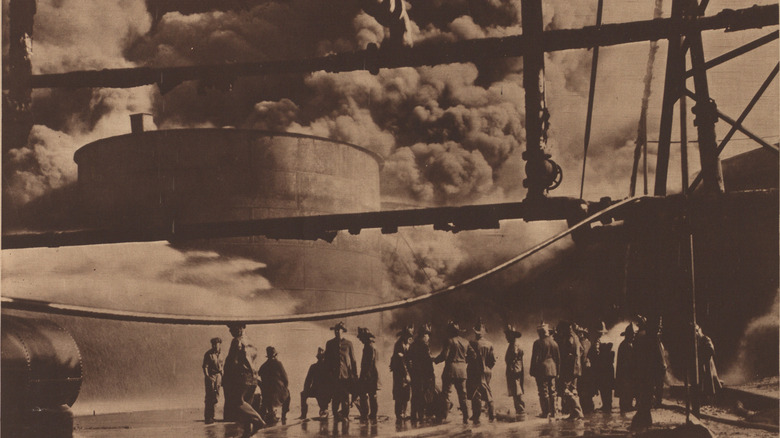

The rise of Standard Oil

The rise of John D. Rockefeller is as much a testament to the Ohio native's cutthroat mentality as his business acumen, and the textbook example of how monopolies dominate competition. Founding his flagship company in 1870, Rockefeller set his firm apart by attacking a little-exploited market inefficiency in the oil industry at the time, specializing in refining oil rather than exploration and drilling processes. Those who know how gas is made might guess what advantages this gave Standard Oil. First, it shielded Rockefeller from the costly overhead of oil exploration. It also enabled Standard to develop processes to remove impurities from otherwise unusable oil, allowing the company to purchase otherwise unwanted oil for pennies on the dollar.

These advantages enabled Standard Oil to both undercut competitors' prices and grow at an unprecedented rate. Pressing this advantage, Standard Oil began to acquire its competitors at what some thought was an alarming rate. Within two years, Standard Oil pushed nearly 85% of its Cleveland-area competitors out of the market. As it expanded, the conglomerate used its size to negotiate transportation rates from the country's railroads, furthering advantages that raised the ire of journalists and politicians alike.

By 1880, the firm had expanded to 20,000 wells and operated enough pipelines to stretch across the United States 1.5 times. Rockefeller broke this vast network into a web of companies managed by boards of trustees in which he possessed over a third of the certificates — a practice now outlawed by the U.S.'s antitrust laws. Soon, Standard Oil became the first company with a billion-dollar stock market value, accounting for about 85% of America's oil sales.

Breaking up an empire

Legal efforts combating Standard Oil's influence began when the Ohio Supreme Court dissolved the company's trust in 1892. This victory was short-lived, as Rockefeller continued the conglomerate's operations in New York unfettered. National criticism of the oil magnate reached an all-time high after the turn of the century, when journalist Ida Tarbell published a book exposing Standard Oil's corrupt and anti-competitive practices.

In 1911, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in a landmark case that Standard Oil violated the 1890 Sherman Antitrust Act, breaking the conglomerate into 34 unrelated companies. It's a ruling that would serve as the backbone of more than a century of American antitrust law. Of these companies, only eight retained some version of the Standard Oil moniker. For Rockefeller, the ruling was less of a blow than you might expect, as the magnate retained his one-quarter ownership stake in the divested ventures, the sales of which elevated him to billionaire status. A century later, Standard Oil's offshoots still dominate the oil industry. For instance, Standard Oil of New Jersey became Exxon and later merged with another Standard Oil descendant, Mobil (Standard Oil of New York), to become the world's second-largest oil company. Chevron, the third-largest oil company, is the result of the merger of Standard Oil of California and Kentucky. Marathon Petroleum, for its part, is the successor of Standard Oil in Ohio. Even British Petroleum got in on the fun when it bought a controlling interest in the Standard Oil Company of Ohio in 1970. By the late '80s, the firm bought the remainder of its Standard Oil Company partner for $8 billion, later merging with Standard Oil of Indiana's successor, Amoco, in 1998.