Here's What Would Likely Happen If The Titanic Sank Today

The shipwreck might be disappearing in our lifetimes, but the story of the RMS Titanic will continue to haunt generations. But if Titanic set sail today and struck an iceberg, it probably wouldn't sink, at least not in the same way. That's because the key risk factors in the 1912 disaster have either been engineered out, regulated away, or now rely on modern detection systems.

First off, the Titanic was traveling at 21.5 knots (which wasn't its top speed) through an area known for icebergs, ignoring at least nine ice warnings. Today, that wouldn't fly. Modern commercial vessels also use satellite GPS, sonar, and live iceberg mapping from agencies like the U.S. Coast Guard's International Ice Patrol. Instead of relying on a lookout in a crow's nest, ships now receive automated warnings backed by real-time satellite and aircraft recon. Since the IIP began its work, no ship that followed its safety lines has hit an iceberg.

The Titanic sank because five watertight compartments were breached, which was more than it could handle. Modern shipbuilding technology is miles ahead of where it was in 1912, but even if the exact same damage occurred today, the outcome would likely be very different. Unless the ship ignored every safety rule and tech advantage available (which was exactly what the Titanic did), a modern replica wouldn't go down the same way.

Modern ships are built to handle more than Titanic could

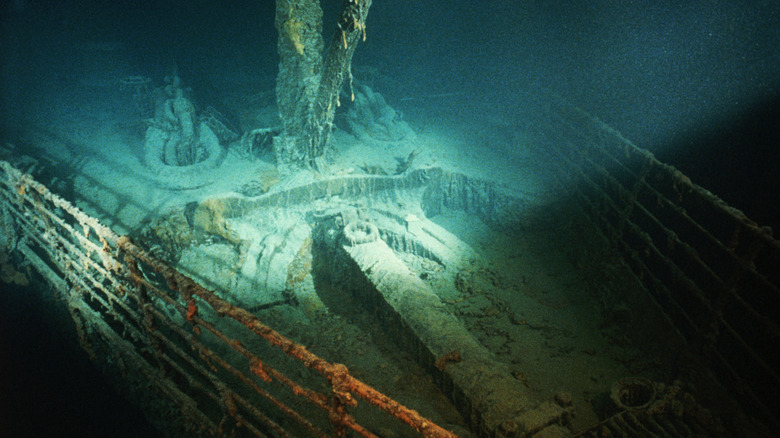

The Titanic broke apart at the surface because its steel and structural joints couldn't withstand the stress of progressive flooding. Metallurgical tests from the Titanic wreckage show its steel was brittle in cold water and that its rivets cracked under pressure. Ships now use notch-tough steel, crack-arresting rivets, and specific chemical compositions of steel for cold-weather performance. Hulls are also designed for greater impact resistance.

According to naval architects and engineers, had the Titanic hit the iceberg head-on, it might have survived. Historical data shows ships like SS Arizona and SS Grampian did exactly that and stayed afloat. The side impact on the Titanic caused long, glancing blows that compromised multiple compartments. But front-end collision zones today are designed with double hulls that absorb impact energy and contain flooding.

When the Titanic split, it happened at a known stress point near the expansion joint under the third funnel. The break began due to weak girder spacing and poorly handled tensile stress. The final tipping point for the Titanic was the brittle fracture of the midsection as the stern lifted out of the water. That level of design failure, combined with fragile materials, would not pass a single regulatory body today.

A modern disaster would unfold very differently

Let's say a ship built today somehow still hit an iceberg and began taking on water. Unlike in 1912, help would arrive within hours, or even minutes. After the Titanic sent its distress calls, the nearest ship, the Californian, didn't answer because its radio operator had gone off duty. Today, distress calls trigger automatic relay across international rescue systems. Systems like AMVER (Automated Mutual Assistance Vessel Rescue) can reroute nearby ships instantly.

Rescue vessels include everything from oceangoing helicopters to 115-meter Coast Guard cutters. In some cases, cruise ships have rescued sailboats within 50 kilometers of detection. Emergency beacons, satellite phones (although illegal in some places), and AIS tracking allow rescue teams to locate a distressed ship even in complete radio silence.

And then there's the lifeboat issue. The Titanic was short on lifeboats for its passengers and crew. That would never happen now. SOLAS regulations (in place since 1914) require enough lifeboats for everyone on board.

Accidents still happen. But ships today are less likely to hit ice, more likely to survive if they do, and dramatically more prepared to evacuate if things go south. If the Titanic sank today, the story wouldn't be about a lack of lifeboats; it would be about how nearly everyone made it out alive.