9 Of The Most Famous Ghost Ships We Know To Exist (And What Happened To Them)

The sea, with its allure of adventure, mystery, and camaraderie, has always held a romantic appeal. The promise of wealth, the sensory delight of sea spray, and the breathtaking vistas have drawn humanity to the ocean since the discovery that wooden vessels could float. However, the ocean, mighty and unforgiving, shows no sympathy for the unwary, unprepared, or, most tragically, the unlucky. For every triumphant voyage, hundreds have ended in desolation, death, and disaster. Some ships have returned covered in glory, while others have vanished over the horizon, lost to history forever. Shipwrecks have captured our fascination for centuries, but what about their spooky cousin, the ghost ship?

While the term 'ghost ship' may evoke images of cheesy movies or myths, the truth is far more sobering. Ghost ships are not the stuff of legend, but a stark reality. They are not the spectral images of the tattered and translucent Dutchman sailing under a full moon. An actual ghost ship is a simple concept, even if the mystery of how it got that way ventures into the absurd or even paranormal. A ghost ship is a vessel that continues to sail even though its crew has abandoned it, or worse.

Ghost ships pop up from time to time, spotted by some watchful lookout or boarded by a curious party. Sometimes, the explanations for how such a situation came about are easily discerned. Other times, the mystery echoes through centuries without any satisfactory answer to the fate of the souls who were supposed to be aboard. We dive into the annals of seagoing history to examine some real-life cases of ghost ships that have sailed the seven seas.

Mary Celeste

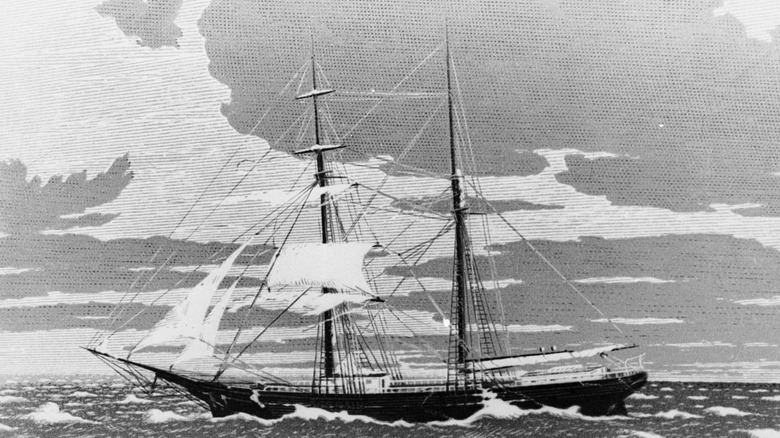

A two-masted brigantine of 282 tons, the Mary Celeste seemed ill-fated from the start. Launched from Spencer's Island, Nova Scotia, under the name Amazon in 1861, her first captain died of pneumonia during the maiden voyage. Following multiple damaging incidents, she ran aground off Cape Breton Island in 1867, after which an American bought her and rechristened her the Mary Celeste.

The Mary Celeste cast off from New York City en route to Genoa loaded with alcohol on November 7, 1872. Aboard were Captain Benjamin Briggs, his wife, their two-year-old daughter, and a crew of seven. Over a week later, the British crew of a brig named the Dei Gratia spotted the Celeste adrift near the Azores archipelago, about 1,000 miles west of the Portuguese coast.

The Dei Gratia's captain ordered a boarding party to investigate, and what they found defied explanation. A longboat was missing, but the captain's log –- always taken when a ship is abandoned –- was aboard, as were the crew's personal effects. Yet it was a ghost ship without a living soul aboard.

Despite an investigation that ruled out foul play, the mystery of the Mary Celeste endures. Why did the crew abandon a perfectly seaworthy ship? One theory suggests Captain Briggs mistakenly believed she was taking on too much water -– a disassembled pump was found in the hold –- and the longboat met some ill fate. Pop culture has spun various theories, from monsters to homicidal pirates, but the truth remains elusive.

The Mary Celeste continued sailing until 1884, when her owner ran her aground off the coast of Haiti in an attempted insurance scam.

Carroll A. Deering

The Carroll A. Deering, a colossal five-masted commercial schooner, set sail from a shipbuilding facility in Bath, Maine, in 1919. Her primary mission was to transport bulk cargo between the east coast of the United States and the Caribbean.

The Deering, on her return journey to Hampton Roads, Virginia, from Barbados, was last spotted by the Cape Lookout Lightship on January 29, 1921. The lightship keeper reported a man on the deck, who mentioned the Deering had lost her anchors but was otherwise in good condition. The next day, the SS Lake Elon observed the Deering on an unusual course.

Coast Guardsman C.P. Brady spotted the Carroll A. Deering rocking on the shoals off Cape Hatteras in the dawn light of January 31. Her decks were awash, but her sails remained up. When the weather allowed the Coast Guard to board on February 4, the boarding party found a meal set for eating, but all personal belongings and lifeboats were gone. The only living souls aboard were three hungry cats.

The case of the enigmatic ship captured the nation's imagination. Five federal agencies launched investigations into the incident. The mystery deepened in April when a note in a bottle was discovered, claiming the Deering had fallen victim to piracy. However, this note was later revealed to be a hoax. Theories explaining the missing crew range from a Bolshevik plot to piracy to the mysterious forces of the Bermuda Triangle. The Deering was eventually towed off the shoals, salvaged, and destroyed, but the truth about her crew's fate remains a captivating mystery.

Governor Parr

In the days before mega container ships, agile schooners did much of the commercial shipping along the coasts of the Americas. The Governor Parr was one such ship. She was one of the final schooners to emerge from the shipbuilding industry in Parrsboro, Nova Scotia, and was the pride of the community until she encountered a storm on her way to Buenos Aires, Argentina, in October 1923. The winds snapped two of her four masts and swept Captain Angus Richards and a crewman to their deaths overboard.

The remaining six sailors lashed themselves to one of the remaining masts, along with the ship's dog and cat. After floating for 36 hours, they were discovered and rescued by the S.S. Schodack. Despite the severe damage, the abandoned schooner continued to sail without a crew for months before a U.S. Coast Guard ship took her under tow — but a storm forced the crew to cut the derelict loose.

However, that was only the beginning of the ghost ship's adventures. Eight months later, a British ship spotted her 800 miles from the Virgin Islands. The British Navy deployed a ship with the express mission of sinking the nautical menace. They located the Parr and set her on fire, but she survived. She was later spotted off the coast of Portugal, meaning she had transited the Atlantic Ocean on her own. Two years later, in 1925, the American Navy made a sighting in the West Indies, meaning she had made the trip back. The U.S. Navy set out to destroy her, but she gave them the slip and hasn't been spotted since. The Parr was carrying over a million board-feet of lumber, which might explain why she was so reluctant to sink.

Baychimo

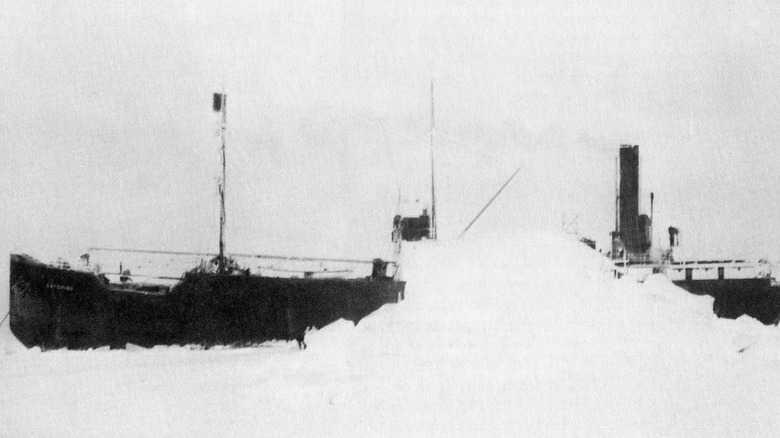

If you think the Governor Parr stayed afloat for an improbably long time, wait until you hear about the SS Baychimo. Originating in the shipyards of Gothenburg, Sweden, the Baychimo was a sturdy steel steamship of 230 feet launched in 1914. She was explicitly designed to ply the northern climes, with an ice-breaking bow that aided her on duties in the Baltic Sea toward the end of the First World War. Her design, which included reinforced steel hulls and a powerful steam engine, made her a formidable vessel in the harsh Arctic conditions.

After the war, the ship ended up in the hands of the Hudson Bay Company, where she was tasked with sailing from Vancouver to the Yukon Territory until 1931, when she became entrapped in ice. The stranded crew sent a party over the ice to nearby Barrow, Alaska. When they returned with supplies, they set up camp on the ice and began offloading the Baychimo's cargo. Unfortunately, a blizzard whipped up. The ship was gone when the men emerged from their shelters the next morning.

Was the ship swallowed by the icy depths, or did she manage to break free from the clutches of the ice? The latter theory gained traction when an Inuit hunter reported a sighting of the vessel 44 miles south of her last known position. The crew returned home, but the Baychimo, it seemed, had other plans. She continued her solitary journey, making several appearances over the years, steadfast in her determination to stay afloat. Her last confirmed sighting was in 1969, a staggering 38 years after her initial disappearance. While she's likely met her watery end by now, who's to say for sure? Perhaps you'll be the one to spot her on your next ice fishing trip.

SM U-118

The First World War introduced the world to the lasting impact of the submarine. Initially, German submarine crews surfaced and ordered unarmed merchants to abandon ship under threat, but the uses of World War I submarines expanded as the war wore on. Submarines eventually became a major deep-sea threat, attacking trans-oceanic shipping from the depths. This is why it was such a shock when, in April of 1919, the residents of Hastings, United Kingdom, woke up to find a massive ghost submarine sitting on a popular tourist beach.

The warship looked massive sitting cocked to one angle, high and dry on the sands. She was the SM U-118, a German boat that launched in February of 1918 and was tasked with laying mines across open ocean shipping lanes. When the shocked locals went aboard, they found the ship devoid of any crew, making her a bona fide ghost ship.

The German navy had surrendered U-118 to the Allies in February 1919. While being towed between Harwich, England, and Brest, France, a gale rose up, causing her tow line to snap. Unmanned and out of control, she drifted ashore to perch in front of one of Hastings' finest beachside hotels. The British turned her into a tourist attraction, but the novelty eventually wore off. Three months later, the authorities broke her up for scrap.

S.V. Zebrina

The U-118 was hardly the only World War I-era boat to wash up (or disappear) under mysterious circumstances. In 1917, the war continued to rage on the seas and battlefields of Europe. Perhaps that is why the war figures so prominently in theories about what happened to the crew of the S.V. Zebrina.

By 1917, the Zebrina already had a storied career under her belt. Initially launched in 1873, she measured 100 feet long and weighed 189 tons. Designed to run commercial transport missions in shallow waters, she had a flat bottom and could be operated by a crew of just five. For decades, she worked in the Mediterranean Sea and the English Channel. By 1917, her home base was Falmouth, England, from which she departed on September 15 with a coal load headed for France.

A mere two days later, authorities in France found the Zebrina run aground along the rocky French coast in six feet of water. She was largely undamaged — her rigging in poor order, but otherwise seaworthy. The final log entry indicated her departure from Falmouth, and that was it.

Theories about her abandonment revolve around two central causes: weather and war. Weather is always a good bet for ghost ships (or any sunken ship, for that matter). Could a German U-boat have surfaced and forced her crew to surrender? Or shot torpedoes that run under her deceptively shallow hull? Such actions were not unheard of during the First World War. But no crew members ever showed up on prisoner lists.

MV Joyita

The MV Joyita, a vessel nearly as renowned in seafaring circles as the Mary Celeste, has a storied past. Launched in 1931 as a luxurious yacht for Hollywood director Roland West, she transitioned into a naval patrol boat during the Second World War, and later served as a supply and transport ship in the Pacific.

By 1955, she had seen better days. Departing from Apia in Samoa to the Tokelau Islands, she was laden with medical supplies, a doctor who was required to perform an amputation on the islands, and 25 passengers and crew. Though the crew could not get the clutch of one of her two engines functioning before the trip, Captain Thomas Miller ordered her to depart Apia harbor on October 3, 1955.

The weather was clear and fine, which, along with his debts, may have induced Miller to sail despite knowing the Joyita lacked an engine, and had a pump and a radio in disrepair. The routine voyage was a mere 300 miles. Yet, the Joyita did not appear at her destination. By October 6, the authorities launched a search with Sunderland seaplanes of the Royal New Zealand Air Force, which combed over 100,000 miles of ocean before calling off the search on the 12th.

On November 10, a merchant vessel located the Joyita, half-sunk and drifting more than 600 miles from her original course. The lifeboats were missing, and there was not a soul aboard. The captain's firearms and logbook were missing, and a doctor's bag aboard contained bloody bandages. Despite an inquiry, no solid answer as to the fate of those aboard ever emerged. Today, theories range from weather to mutiny to piracy.

Teignmouth Electron

In 1968, the Sunday Times of London set the yachting world abuzz with an audacious announcement — a solo, non-stop circumnavigation of the globe. The Golden Globe race, as it was named, was a monumental challenge that required sailing westward from England, around the Cape of Good Hope, crossing the Pacific, and rounding Cape Horn to return to England without stopping.

Donald Crowhurst was a 36-year-old businessman born to British parents in India. Crowhurst was a passionate but amateur sailor. Indebted and on the verge of bankruptcy, he collected sponsors by misrepresenting his resume and purchased the Teignmouth Electron, a trimaran sailing yacht. With just a few weeks' practice with his new boat, Crowhurst departed with the rest of the competitors from England in late 1968.

Crowhurst realized almost immediately that he could not keep pace with the more experienced yachters. According to his recovered journal, he devised and implemented a plan that involved stopping for aid in South America and rejoining the race using a fraudulent route. But it was not to be.

On July 11, 1969, a Royal Mail vessel made a haunting discovery — the Electron, adrift and unmanned. The materials onboard revealed a chilling narrative of a man descending into desperation, delusion, and possible suicide. It was a tragic end to a journey that began with such ambition, leaving behind a ghost yacht and a cautionary tale of hubris and the unforgiving ocean.

HMS Resolute

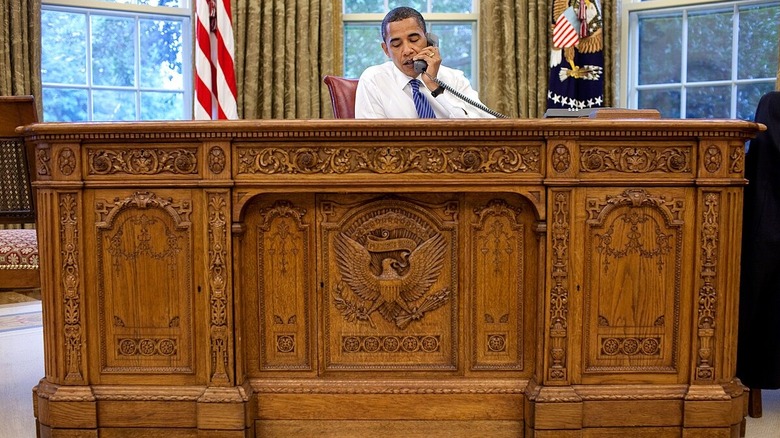

In the golden era of sailing during the mid-19th century, explorers sought a northern route around the American continent. During the ill-fated Franklin Expedition, the HMS Terror and HMS Erebus disappeared into this maw. The British government dispatched search parties, among which was the HMS Resolute.

Regrettably, the crew of the Resolute encountered a similar fate to the Franklin Expedition. The ship was ensnared in ice, a predicament that had led to the disappearance of the entire Franklin crew. However, in a remarkable display of resilience, most of the men from the Resolute expedition managed to abandon the ship and struggle ashore, with the majority surviving the ordeal. Their ship, too, endured.

The crew of a whaling ship spotted a vessel off Baffin Bay in September 1855. Despite their attempts to communicate with the ship, they received no response. A four-man boarding party was dispatched to investigate. To their astonishment, they found the ship to be unmanned. It was soon identified as the HMS Resolute, a staggering 1,200 miles from her last known location. The whalers, disappointed by their unsuccessful expedition, decided to salvage the Resolute.

A torrent of correspondence and intrigue followed. The upshot was that the U.S. government purchased the Resolute and returned her to England as a gesture of goodwill between the nations. Refitted and restored, she sailed into England to cheering crowds. Queen Victoria even toured the ship.

When the Resolute was decommissioned in 1879, the British returned the gesture. American President Rutherford B. Hayes received a desk made from the ship's timbers. Since then, nearly every president has used the desk built from the once-ghost ship in the Oval Office.