The Human Rocket Ride: The Story Behind John Stapp's Ultimate Speed Test

It was December 10, 1954. The end of World War II was less than a decade in the rearview mirror of the world's collective consciousness, and the rocket age was booming. A United States Air Force flight surgeon and Colonel by the name of John Stapp was at Holloman Air Force Base in New Mexico, preparing to do something that defies logic.

Millions died horrifically during the war, a dark period that also saw some of the most significant scientific and technological advances in human history. What's more, the great space race was on the cusp of launching man into a new era.

John Stapp was anything but a show-off or risk-taker, nor was he crazy. He wanted to be a writer. However, after experiencing the death of his infant cousin in 1928, he decided to become a doctor instead. He attended Baylor University, initially earning a Bachelor's in English in 1931.

He didn't have the money to enroll in medical school, so he obtained a Master of Arts in Zoology (in 1932) instead. Stapp taught for two years before attending the University of Texas at Austin, where he earned a Ph.D. in Biophysics (1939) and finally became a Doctor of Medicine in 1944 while at the University of Minnesota.

This Doctor was willing to experiment on himself

Dr. Stapp entered the US Army Air Forces on October 5, 1944, and became both a physician and a flight surgeon, taking care of the unique health concerns aviators encountered while flying at high altitudes. In August 1946, Stapp was assigned to Wright Field, where he began working in the Aero Medical Laboratory, tasked with assessing different oxygen systems in unpressurized aircraft at altitudes of 40,000 feet.

There was concern over pilots of high-altitude planes getting "the bends" or decompression sickness. Additionally, very little was known regarding what high altitudes did to human physiology, and safety guidelines and aircraft standards were almost non-existent. Wanting to understand all this and unwilling to risk other's lives, Stapp routinely performed tests himself.

His experiments and subsequent findings helped define systems for future fighter jets and insertion protocols for High Altitude Low Opening (HALO) jumps. Stapp transferred to the US Air Force when it became a branch of service in September 1947.

Having proved himself on that project, Stapp was assigned to study how G force deceleration affected the body at Muroc Dry Lake (now Edwards Air Force Base) in March 1947. Over the following year, Stapp personally subjected himself to 16 rocket sled runs, some of which assaulted his body with as much as 35 Gs. In 1953, Stapp was transferred to Holloman Air Force Base to continue his studies, where his date with the rocket sled known as Sonic Wind No. 1 awaited him.

Sonic the Rocket Sled

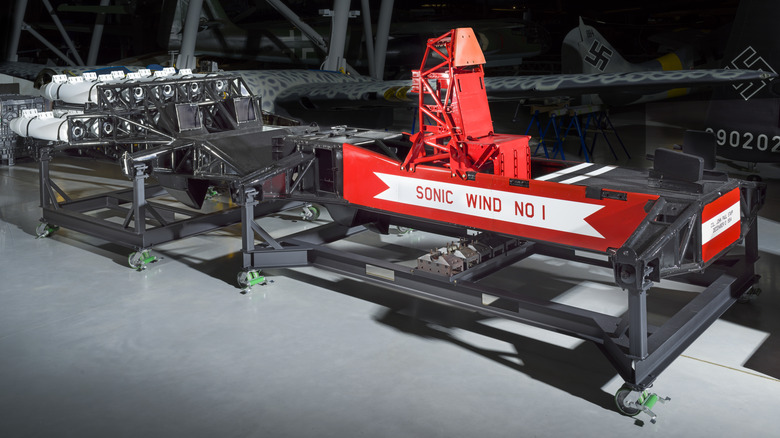

After arriving in New Mexico, Stapp began working on the Sonic Wind No. 1 rocket sled with the Northrop Corporation. It was designed with a replica jet fighter seat and a propulsion section comprised of six solid-fuel rockets. The braking system consisted of a scoop attached to the front of the sled that would dig into a successive line of water dams that would help soak up the kinetic energy and eventually slow the sled to a stop, with the hopes that Stapp wouldn't sustain any permanent injuries.

Stapp's first run happened on March 19, 1954. The half-dozen rockets created 27,000 pounds of thrust, drove him 421 mph, and exerted 22 Gs onto his body. A second run conducted in August boosted the speed to 502 mph (735 feet per second).

On December 10, he boarded the sled — now equipped with nine rockets– for his last run. Since there was nothing to deflect the incredible wind velocity, his arms and legs were strapped down to keep them from thrashing. Additionally, he wore a helmet and used a bite block to protect his teeth.

Sonic Wind No. 1 ignited 40,000 pounds of thrust, propelling Stapp 632 mph and creating some 46 Gs (the equivalent of almost four tons). The entire ride from ignition to complete stop lasted all of 1.4 seconds. For the briefest moment, his body weighed 6,800 pounds, and the deceleration force was that of a car hitting a brick wall at 120 mph.

Stapp yourself in and always wear your seatbelt

The violent ride wreaked havoc on his body, cracking ribs and breaking both wrists. He was temporarily blinded because the G forces burst all of the blood vessels in both eyes. Even his respiratory and circulatory systems were briefly affected. Fortunately, none of these injuries were permanent. His accomplishment set a world land speed record and earned him the nickname "Fastest Man on Earth" from Time Magazine.

Ultimately, Stapp's efforts proved that pilots could safely eject from a plane traveling at 1,800 mph at an altitude of 35,000 feet and could survive a crash up to 45 Gs – as long as the seat didn't break loose and the pilot was restrained correctly with an appropriate protective harness. From his data, pilot seats were strengthened, and seat belts were improved.

Stapp was confident that his work with airplane safety could be transferred to automobiles, so the Air Force "loaned" him to the civilian National Highway Traffic Safety Administration in 1967. His knowledge and research were used to help create many of the first transportation safety standards, specifically those that advocated for and improved the use of seat belts and shoulder harnesses in cars.

The Sonic Wind No. 1 was moved to the Smithsonian in 1966 and is currently on display in the Nation of Speed exhibit at the National Air and Space Museum in Washington, DC. Colonel Dr. John Stapp was 89 when he died on November 13, 1999.