10 Little-Known Heroes Of Military Aviation

The battle for control in the skies is often imperative to securing the overall success of a military campaign on the ground. Since World War I, we have seen belligerent forces head to head in aerial combat. However, there is much more to the story of military aviation than dogfighting aces and bombing campaigns alone.

While much is said of aerial battles, raids, and various conflicts, many unsung individuals and smaller groups' efforts helped shape military aviation history. These men and women were not only heroes on the battlefield but were also instrumental in building new technologies, training personnel, administrating forces, and breaking social divisions to become pioneers within their respective fields. In doing so, they continue to influence how we protect our borders from above.

The following important figures deserve recognition as heroes of military aviation. Whether they played a supporting role as part of a squadron or helped push the boundaries of what can be achieved by aerial fighting forces, their achievements are as influential as they are impressive.

Jesse Leroy Brown

The Tuskegee Airmen were famed in history as the first African-American unit to serve in the United States Air Force during World War II, but the U.S. Navy had no such equivalent training program. Jesse Leroy Brown made history as the first African-American to earn the coveted "Wings of Gold" naval aviator badge and serve in the U.S. Navy, overcoming much military discrimination and outright racism as he worked his way up the ranks.

Having earned his Navy flight training wings in 1948, Brown was assigned to a fighter squadron aboard the aircraft carrier USS Leyte and was soon to see action in the Korean War. In December 1950, his company was ordered to provide air support to 15,000 troops on the ground, and he flew multiple missions in poor weather conditions to escort trapped U.S. Marines out of Chinese territory. After several successful attempts, his luck finally ran out when he was struck by ground fire and forced to ditch his plane behind enemy lines.

Despite a valiant rescue attempt from his wingman, Lieutenant Thomas Hurdner, Jesse Leroy Brown could not be extricated from the burning fuselage of his aircraft. He will go down in history as a trailblazing African-American naval aviator who gave his life for his fellow service members. Brown was awarded a posthumous Purple Heart, Air Medal, and Distinguished Flying Cross for his remarkable service to his country.

[Featured image via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | Public Domain]

Jeanne M. Holm

Not all those who serve in the military ever engage in combat, but they are nonetheless vital to helping secure our national borders and protecting our allies' interests overseas. Jeanne Holm was one such officer who started her career as a commander assigned to train female forces for active duty. Having earned her bachelor's degree, she was recalled to the military, where she served in the Air Force, first in Berlin, Germany, before being transferred to Asia to serve in the Korean War.

In 1952, Holm became the first female officer to attend Air Command and Staff training school before being transferred to Washington, then Naples, Italy, as chief of staffing at the NATO headquarters. She received the Legion of Merit honor for her service dedication before returning to the U.S.

Holm went on to champion women's roles in the U.S. Air Force and eventually became the first woman to be promoted to the rank of Brigadier General. She is among the most decorated women to have served in the U.S. Air Force, eventually being appointed to the position of director of the Secretary of the Air Force Personnel Council. Jeanne M. Holm was promoted to Major General in 1973 and became a successful author before dying of pneumonia in 2010.

Douglas Bader

Few servicemen could be said to represent the resilient attitude of Allied soldiers in World War II better than Douglas Bader. As an inspirational British RAF pilot, Bader achieved notable success despite losing both legs in a pre-war flying accident before being forced to bail out over France and being captured as a German prisoner of war and held in the notorious Colditz Castle.

Having been fitted with artificial legs, Bader was able to walk again and qualified for active service as a Spitfire pilot when war broke out in 1939. He was the leader of the 242 Squadron during the Battle of Britain when the U.K. fought off Germany's attempt to invade from the skies. Having been promoted to Wing Commander, he was engaged in the dogfight that left him captured after losing one of his artificial limbs during the bailout.

After finding and repairing the leg, Bader made the first of three unsuccessful escape attempts. He soon found himself transferred to the Stalag Luft III camp, where he met plotters behind the celebrated "Great Escape," which became a classic movie with Steve McQueen. Due to his enthusiasm for escaping and generally messing with German authorities, Bader was sent to Colditz, which was deemed inescapable. Here, he assisted escape committees until the end of the war before being repatriated to the U.K., where he was knighted by the Queen in 1976 for his services to the disabled community.

Jacqueline Cochran

While many of us have heard of the exploits of Amelia Earhart as an early female pioneer of aviation, Jacqueline Cochran flies under the radar of many contemporary accounts. However, she is arguably just as inspirational, with many outstanding achievements to her name. Among them, Cochran organized and led the Women's Flying Training Detachment in World War II and was instrumental in advocating for the integration of women into military aviation roles in the United States, leaving an indelible mark on how the Air Force is organized to this day.

Having set several early speed records in fixed-wing aircraft and entered into international air races, Cochran created her own cosmetics company, "Wings of Beauty," before serving in the United States military, organizing aerial transport with 27 female pilots under her command. She then formed and became director of the Women's Airforce Service Pilots (WASPs), performing various transport and logistical duties during World War II.

By the time Jaqueline Cochran died in 1980, she had broken more aviation records for altitude, distance, and speed than any other pilot of any gender. She had been awarded the Distinguished Service Medal and Distinguished Flying Cross, honoring her military achievements, and had risen to the rank of colonel. She continued to set records in retirement from the military, reaching Mach 2, or twice the speed of sound, in a Lockheed Starfighter at 58 years of age, as a testament to her incredible resolve.

Charles Kettles

Charles Kettles was the son of a Royal Canadian Air Force pilot whose family moved across the border. As a U.S. citizen, he was drafted into the U.S. Army at 21 years of age, and having graduated from the Army Aviation School, he immediately went on to fight in Korea in 1953. After the war, he became an army reserve and entered civilian life. But soon, he was called upon to serve in Vietnam, transitioning from fixed-wing duties to training as a helicopter pilot, flying the relatively new Bell UH-1 "Huey."

Kettles' most heroic actions were recorded during the battle of Duc Pho when he led the extraction of dozens of injured U.S. troops from an intense battle zone. His flight of six helicopters soon came under enemy fire. After one successful series of evacuations, his damaged Huey was called upon to reenter the battlezone multiple times to rescue yet more troops. In his final sortie that day, he went back unaccompanied to save the remaining eight soldiers, with little regard for his own safety. He ultimately helped save 44 troops from certain death.

Charles Kettles received the Medal of Honor for his actions in Vietnam and is one of the most decorated helicopter pilots to have served in the U.S. military. His many other accolades include the Distinguished Service Medal and Distinguished Flying Cross. He also achieved bachelor's and master's degrees while in the army and lived out his career working in aviation management before retiring.

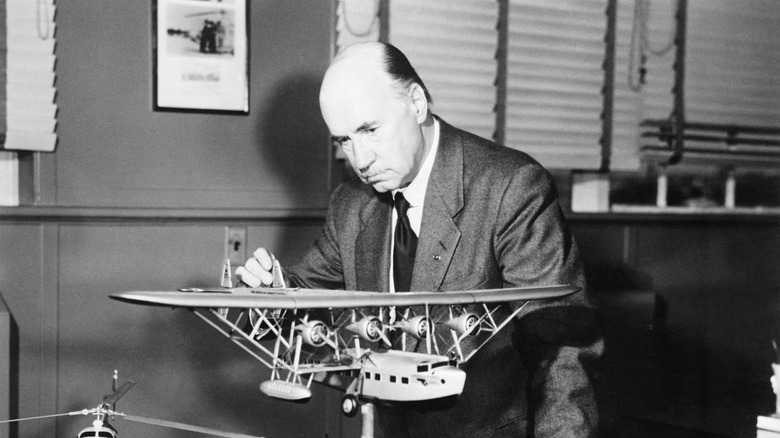

Igor Sikorsky

In his early days, Igor Sikorsky's native Ukraine was still part of Russia, but the maverick aviation engineer was so gifted he was sent to study in Paris and soon formed a successful aviation company in the United States. While he had impressive results designing transatlantic flying boats, it was helicopters that really captured Sikorsky's imagination.

As a pioneer of the helicopter, he was credited with the 1939 invention of the first successful model, the VS-300. This served as the foundation upon which all modern helicopters are based and is a remarkable feat of engineering. Unlike fixed-wing aircraft, these seemed to defy physics by punching through the air to provide lift, lending them considerable practical purpose without the need for takeoff and landing space. The U.S. military quickly saw a requirement for these relatively new machines, initially as medivac vehicles, and ordered hundreds of units from the Sikorsky company by the end of World War II.

Working with the Lockheed-Martin company, the Sikorsky name became associated with some of the most globally recognized military helicopters. These include the UH-60 Black Hawk and SH-60 Seahawk models, which are still widely used today. It was the technology that came to define the many years of conflict in Vietnam in what was to be known as the "Helicopter War," the Sikorsky legacy continues to live on with each successive generation of these remarkable machines.

Dennis M. Fujii

We often hear of acts of bravery from troops in combat. Still, medical teams are among the most vulnerable and gallant among them, as their job is to ferry the injured from battle zones and administer aid in the most hazardous of circumstances, often as firefights rage around them. Hawaiian native Dennis Fujii was a crew chief aboard a U.S. helicopter ambulance during the Vietnam War, and he found himself in one such situation in late February 1971, where he was called upon to overcome fear in the face of extreme danger.

Fujii's mission that day was to evacuate injured Vietnamese allies from a battlefield in Laos as enemy forces rained mayhem around them. It was a turkey shoot in which medical personnel were the target, and on his second attempt, Fujii's chopper sustained severe damage from flak, and he crash-landed, sustaining injuries. He radioed his team and warned them off a rescue attempt as the area was too dangerous, remaining on the ground as he administered aid to the injured.

For 17 long hours, Dennis Fujii remained under heavy fire, assisting attack helicopters in destroying enemy positions, until he and the injured were finally evacuated. He received the Distinguished Service Cross, two Purple Hearts, and a Silver Star medal for his efforts and was awarded the Medal of Honor in 2022.

Kelly Johnson

Just as it had found success working with Igor Sikorsky, the Lockheed-Martin company was keen to take another young maverick under its wing in the years leading up to World War II. His name was Clarence "Kelly" Johnson, and he was hired at the age of 22 for his ability to find and rectify flaws in existing plane designs. A few years later, as war encroached upon the United States, Kelly was called upon to support its allies overseas in their aircraft designs and very soon was designing military aircraft for America's own war efforts.

Johnson was responsible for designing some of history's most iconic military aircraft. These include the world's first jet fighter, the P-80, the constellation, and the U-2 spy plane. He was known for his ability to execute projects, from conception to completion, in a matter of months, which proved to be highly useful in wartime, as emerging technologies were pitted against each other and, later, in commercial aviation, as companies vied to have the edge on their competition.

Despite a fiery nature and no-nonsense approach to executing successful projects, Clarence "Kelly" Johnson was a much admired and well-liked persona by those who worked with him. He also gained recognition from the United States military for his efforts, having been awarded the National Medal of Science, Medal of Freedom, and National Security Medal for his contributions to the defense sector.

[Featured image via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | Public Domain]

Frank Whittle

There are many unsung heroes, both in peacetime and in wartime. While British inventor Frank Whittle was eventually recognized for his efforts as the creator of the turbojet engine, he wasn't given the attention he deserved by the British government when they needed him the most.

Whittle understood as early as 1928, while he was at the Royal Air Force College, that an aircraft that flew higher and faster than the current internal combustion engines would allow would place the U.K.'s military at a significant advantage. Within a year, he had devised the turbojet engine. However, it wasn't until 1941 that his prototype was realized in the Gloster E.28. Jet aircraft were eventually used for intercepting the jet-powered V-1 rockets that Germany reverse-engineered based on Whittle's creation and fired at London towards the end of World War II. However, it was too little too late, and this new technology wasn't used to significant effect by the Allies during the conflict.

Soon, jet aircraft would be employed by various militaries in the Korean and Vietnam Wars and became an essential component of modern aerial warfare, as well as commercial air travel. After the war, Frank Whittle was finally given recognition, and he was awarded the Legion of Merit and knighted by the Queen of England for his efforts. He later became a research professor at the U.S. Naval Academy in Maryland.

The Colditz Glider Plotters

The Saxony stronghold of Colditz Castle, with the designation Oflag IV-G, was one of the most notoriously secure prisoner-of-war camps during World War II. It was used to house many Royal Air Force personnel due to their propensity for escape. During their confinement, a small team of resourceful British POWs built a working glider from improvised parts in the attic in a daring escape attempt.

The leader of the budding escapees was Bill Goldfinch, who was inspired to build a glider when he noted updrafts around the high castle walls and an obscured potential launching zone in the chapel roof. The plan was approved by Dick Howe, leader of the escape committee, and Goldfinch enlisted his friend Jack Best to assist in the glider's construction.

Construction began in earnest by building a false wall to hide the work being carried out behind and trapdoors through which to pass components. The team used kitchen cutlery to make tools and repurposed floorboards for the frame, with bedsheets stretched across the wings and fuselage. After many months of arduous work and constant fear of detection, the almost 20-foot-long glider was ready.

The maiden flight was scheduled for early 1945, and the plan was to cross the town of Colditz and its adjacent river to land far beyond the reach of German forces. The war ended before the Colditz Glider flew, but modern reconstructions have shown that the escape may well have been a success. Only one image remains as evidence of the incredible efforts of the ingenious would-be escapees.

[Featured image by Sören Kusch via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | CC BY-SA 3.0]