10 Electric Cars That Shaped EV History Before Tesla Even Existed

The switch to electrification is the single biggest change that the automotive industry has seen in living memory, with EVs evolving from being a niche interest to a global phenomenon in the space of just a couple of decades. Their popularity has been driven by recent advances in battery technology and concerns about the environment, but let's not forget — they're also inherently better than regular combustion cars in several key ways. It can be easy to assume that today's industry leaders like Tesla are responsible for developing the blueprint for modern EVs, but many basic EV principles can be traced back to cars manufactured a hundred years ago or more.

In the earliest days of carmaking, electric, steam, and gas-powered vehicles were roughly neck-and-neck, each one having its own unique drawbacks that its respective manufacturers were working hard to overcome. Gas-powered cars eventually won the race for dominance, but even in the decades after the last dedicated EV makers collapsed, several automakers continued developing and producing electric cars. They never saw widespread success until a certain Elon Musk propelled his fledgling car company into the global spotlight, but these 10 cars were all shaping EV history long before the first Tesla rolled out of the factory.

Electrobat

The Electrobat began as a project between two engineers, Henry Morris and Pedro Salom, in 1894. The pair built the car in just two months using a modified ship motor powered by lead-acid batteries, and it was heavy, slow, and oddly proportioned. Nonetheless, initial trials proved that the Electrobat had plenty of potential and a range somewhere north of 50 miles. Morris and Salom unveiled a revised design shortly after, christening it the Electrobat 2. This new vehicle weighed less than half that of the original, and it was quickly put to work as a taxi, ferrying passengers around New York City.

The limited range of the Electrobat was its biggest drawback, but its engineers had designed a system for swapping the battery in just a few seconds using a crane. This allowed it to drive around the city all day, as whenever it was running low on charge, the driver simply headed back to the central depot for a battery swap. A couple of years later, the fledgling car company was bought out by William Whitney, a well-known New York City investor, and he expanded the firm significantly, setting up similar networks of electric taxis in cities across the U.S. and abroad.

However, it turned out that these operations couldn't be made profitable fast enough, and the company began quickly losing ground to gas-powered automobiles. After allegations of fraud were levied against the firm, it collapsed, with its network eventually being shuttered altogether.

[Featured image by New York Tribune via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | Public Domain]

Egger-Lohner C.2 Phaeton (Porsche P1)

Porsche might be best known for its high-performance internal combustion vehicles, but the first ever Porsche car was, in fact, an EV. It didn't bear the Porsche name, at least not officially -– it was originally presented as the Egger-Lohner C.2 Phaeton. However, Ferdinand Porsche, who designed, built, and later raced the car himself, had engraved P1 onto all the major components, giving the vehicle its unofficial nickname.

It produced three horsepower but had an overdrive mode that could temporarily generate up to five horsepower. With overdrive engaged, the vehicle could reach speeds of up to 22 mph. It proved to be reliable as well as fast, winning a race at the 1899 international motor exhibition in Berlin by a significant margin. Porsche completed the 25-mile course around 18 minutes ahead of second place.

After disappearing from the public eye for decades, the P1 was eventually found and returned to the care of technicians at the Porsche Museum in 2014.

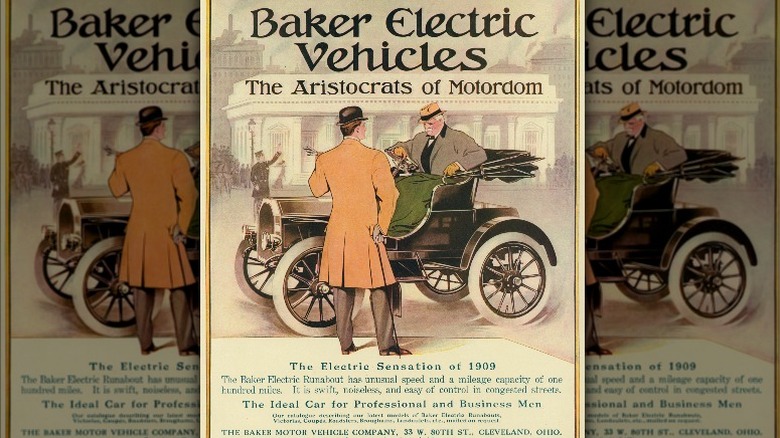

Baker Imperial Runabout

In 1899, the freshly-founded Baker Motor Vehicle Company debuted its first model, the Imperial Runabout. It became the first commercially-available EV in America upon its release and quickly became popular with the celebrities of the day, including Thomas Edison and former First Lady Helen Taft. Company founder Walter Baker was also interested in the land speed record and attempted to break it on several attempts, although none were successful. A crash while attempting the record in 1902 saw two spectators killed, and Baker was briefly arrested for manslaughter.

Before long, the charges had been dropped and Baker was free to continue expanding his eponymous car company, adding extra models to the lineup and promising to add battery-charging infrastructure throughout his native Cleveland, Ohio. This plan was later abandoned as it proved too expensive, and Baker's electric vehicles eventually lost out to the increasingly refined gas-powered cars that were beginning to enter the market. The company eventually shuttered in 1915, joining the ranks of defunct car brands that couldn't compete in an increasingly crowded market.

Le Jamais Contente

The concept of the land speed record was unintentionally created by a French automobile magazine in 1898 when it held trials between carmakers to see who had the fastest machine. The contest turned out to be very popular and drew international attention, and out of that initial contest, the world's first purpose-built land speed record car was created. Le Jamais Contente, translating as never satisfied, was designed by Belgian EV maker Camille Jenatzy in response to Jenatzy losing out to his French rival Count Gaston de Chasseloup-Laubat in the initial speed contest.

After his initial defeat in a more conventional-looking machine, the Belgian unveiled his new, streamlined car, which was made of a lightweight metal alloy and packed two electric motors for an output of roughly 68 horsepower. It proved to be enough to beat the Count, comfortably eclipsing the Frenchman's 57 mph record in April 1899, with a maximum recorded speed of 65 mph. In the process, Le Jamais Contente became the first automobile to break the 100 km/h (62 mph) barrier. The record would eventually be broken three years later, not by an electric car, but by a steam-powered car, which reached 75 mph. That record only stood for a few months before a gas-powered car broke the record by a tiny margin, reaching 76 mph in late 1902.

[Featured image by Alexander Migl via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | CC BY-SA 4.0]

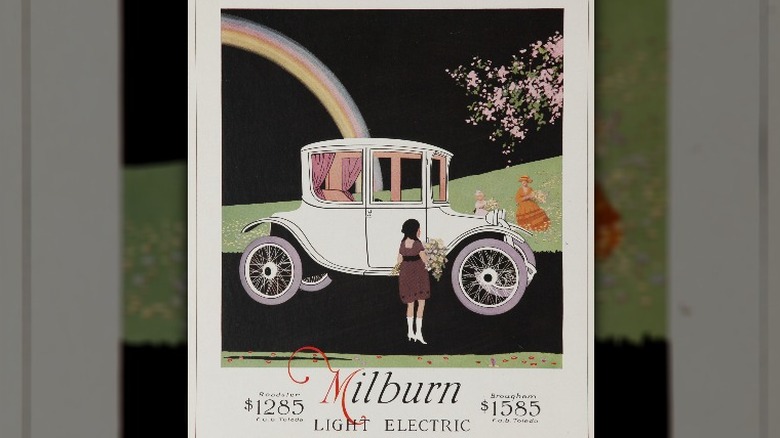

Milburn Electric Light Brougham

Milburn Wagon Company began making electric vehicles in 1915, and sales quickly proved strong. The company sold around 1,000 units in its first year and 1,500 units the year after, with a range of body styles being launched to cater to the widest possible audience. The most successful of those was the Electric Light Brougham, which as its name suggests, was one of the most lightweight EVs on sale at the time. It was also one of the cheapest, helping it compete against the wave of gas-powered cars hitting the market. Milburn eventually sold over 4,000 examples of the car, although very few are thought to survive to the present day.

Later models of the Electric Light Brougham featured removable batteries, which could be replaced quickly and easily. With an extra set of batteries, the car boasted 100 miles of range -– no mean feat for an EV that's now over a century old. Unfortunately, slowing electric car sales saw Milburn's fortunes wane and in 1923 it was bought out by General Motors, with its assembly plant subsequently being used to produce bodies for Buick.

Detroit Electric

Among the longest-lasting of the early electric car companies was Detroit Electric, initially known as the Anderson Electric Car Co. of Detroit. Its first car was manufactured in 1907, and within a few years, leading industry figures including Thomas Edison and Henry Ford had purchased one. This fact was used to promote the company in its advertising material, including one 1914 advert which listed every car company executive that drove a Detroit Electric at the time. This clever marketing, combined with the car's modern design, saw it remain popular even after other electric carmakers were starting to fall into bankruptcy.

The Detroit Electric wasn't just popular in America, either -– it became a hit with wealthy professionals in Australia, as well. Sales continued well into the 1920s, but as gas-powered cars became more refined, sales of the Detroit Electric eventually dwindled. Focusing on electric delivery vehicles saw a partial reversal of fortune, but the Great Depression eventually killed off the automaker, which managed to build over 35,000 vehicles before it shut its doors in 1939.

[Featured image by Cullen328 via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | CC BY-SA 3.0]

Sebring-Vanguard CitiCar

Throughout the mid-20th century, the development of EVs was largely non-existent, as there was simply no demand for them -– gas was plentiful, and so was the American interest in large, high-margin vehicles. However, the oil crisis of the '70s meant there was a renewed interest in electric power, even if actual EV technology had barely advanced since the '20s. One of the hastily improvised solutions was the Sebring-Vanguard CitiCar, which was produced for just three years and featured a motor making a measly five horsepower. For context, the Porsche P1 of 1899 was just as powerful.

The CitiCar could just about reach 40 mph and had a range of around 40 miles, although it was significantly cheaper than most gas-powered cars at the time. Like any startup car company, Sebring-Vanguard had its fair share of quality control issues, and the CitiCar was hit with three separate recalls during its short time on sale. The first of those concerned the seatbelts, which had been installed incorrectly, making them potentially "impossible to wear," according to the NHTSA. A year later, 499 CitiCars were recalled as the brakes could temporarily fail, and then an even larger recall was issued shortly after because of a fire risk caused by short-circuiting wires.

Despite its inherent flaws, around 2,000 examples of the car were sold. However, by 1977, fears around the oil crisis had subsided, orders dried up, and Sebring-Vanguard was forced to declare bankruptcy.

Chevrolet Electrovette

Originally unveiled in 1978, the Electrovette was designed in response to the widely held belief that gas prices would continue rising sharply throughout the '70s. Work on the concept started in 1976, with the aim of making an electric car that would be affordable to the masses and pack reasonable performance. Initially, nickel-zinc batteries were used to power the car's 63 horsepower motor, but they were later replaced with lead-acid batteries in an attempt to keep costs down.

Chevrolet claimed that the Electrovette could reach speeds of up to 53 mph and could travel up to 50 miles at 30 mph. Those figures might have been enough to persuade a few buyers at the height of the oil crisis, but by the time the car was unveiled, fears over gas prices had largely died down. The car's unimpressive range and low top speed simply couldn't compete with the affordable gas-powered cars on the market at the time, so Chevy quietly shelved the Electrovette project and ceased EV development.

GM EV1

You could argue that the GM EV1 was way ahead of its time, and it was, to a degree. However, it was also very much a product of it's own time –- the pioneering EV demonstrated that there was a market for electric cars, but it also proved that that market was still too small to justify further development costs. Likewise, the battery tech was advanced enough to make a fully functional, surprisingly brisk road car, but it wasn't anywhere near ready to compete with the internal combustion engine in terms of range.

GM was already researching the possibility of making an EV by the time California's zero-emissions mandate arrived, but the new law gave bosses a reason to give production the green light. A total of 1,117 examples of the car were produced and leased to customers, but after those three-year leases ended, GM collected all the cars back and destroyed all but a handful of them.

This was purportedly for safety reasons and to protect the car's technology from being reverse-engineered by a rival, but it left a sour taste in the mouth of many owners, who'd become very fond of their cars in the years they'd had them. The remaining examples were donated to museums or universities, although their powertrains were disabled before GM let them go.

AC Propulsion tzero

It might have remained virtually unknown to most enthusiasts, but the AC Propulsion tzero roadster played a vital role in shaping modern EV history. Only three examples of the car were built, essentially as a technology demo to showcase the company's primary focus — making EV drivetrain systems. Elon Musk was persuaded to test drive one in 2003, and he was so impressed he asked the company if it was looking to commercialize the car. After all, it was completely unlike any other electric vehicle at the time – it boasted a range of around 200 miles and a 0-60 mph time of just 3.6 seconds.

The team at AC Propulsion wasn't interested in building a production version of the car, but they introduced Musk to Martin Eberhard, Ian Wright, and Marc Tarpenning, who had just formed Tesla Motors. Musk invested in the newly-formed company and used the tzero as a starting point for designing Tesla's first production vehicle, the Roadster. The success of this initial sports car led Musk to begin work on higher-volume, more affordable electric vehicles, but that might never have happened at all if he hadn't driven the tzero prototype 20 years ago.