A New Island Just Appeared In The Pacific Ocean: Here's How

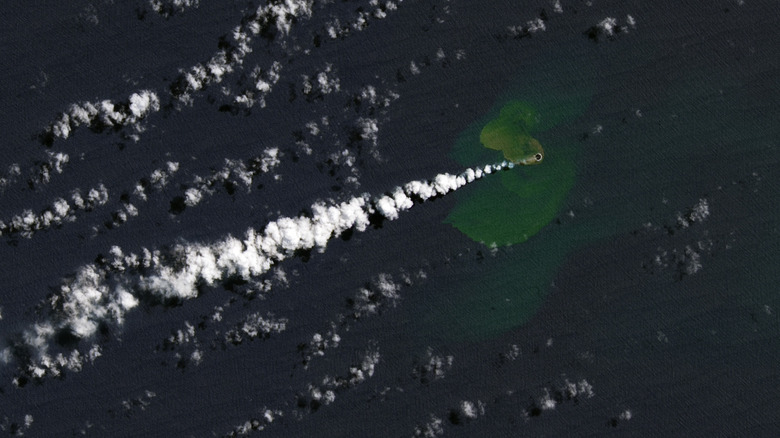

Volcanoes are one of the most destructive showcases of mother nature, but on a few occasions, the monstrous spectacle also gives birth to a new island that may or may not survive the tides of time. One area, in particular, known for such mind-bending natural phenomenon is the thin strip of seabed connecting New Zealand to Tonga, home to a whole host of underwater volcanoes that make their presence known from time to time. That's just what happened on September 10th, 2022, when one of the volcanoes in the Home Reef region of the Central Tonga islands started erupting. Scientists have been hard at work developing ways to predict eruptions, but there's no giveaway quite like the fact that, in less than a day's time, an island had taken shape at the spot.

The volcanic eruption is not surprising, since it falls in one of the most tectonically disturbed regions on the planet. Ever since the volcano became active, it has continued to spew gas and steam that managed to rise up to three kilometers above the sea level. Impressive, though by way of comparison, the devastating Mount St. Helens eruption shot plumes that rose as high as 31 kilometers.

According to data recorded by NASA's Earth Observatory, after just four days from this latest volcanic activity beginning, the new island in the Home Reef region already measured an acre across. In a span of six days, the island's surface area expanded to over six acres. However, it is unclear how long the island will be there, before the ocean reassimilates it.

Not the first of its kind

The Government of Tonga (via The Tonga Geological Services) has issued a hazard alert in the wake of the eruption. Mariners have been advised to stay at least four kilometers away from the area, while the aviation sector has been relayed a yellow alert. Thankfully, the residents of the nearby Vava'u and Ha'apai areas are in the safe zone. As for the island, well, it's no picnic spot, since the water in the volcanic area is highly acidic with high sulfur content and hot plumes consisting of steam and ash. This is not the first time that the region has witnessed volcanic activity that paved the way for a short-lived island, either.

Twice, in 1984 and 2006, the Home Reef region recorded volcanic activity, producing ephemeral islands with peaks as high as 70 meters. This island genesis behavior is not unique to the Home Reef, too: the 12-day-long eruption fest from the nearby Late'iki volcana in 2020 produced an island that only survived for about two months, before being washed away. That's not to say volcanic islands can't survive longer. A total of six eruptions — in 1851, 1894, 1967–1968, 1979, 1995, and 2019 — have been recorded at the Late'iki Volcano, with the one happening in 1995 creating an island that lived for 25 years, according to a paper published in Science Reports.

How do volcanic islands form and die?

The geological nature of short-lived volcanic islands differs based on the chemical composition of the lava itself, but the fundamental process remains more or less the same. Take, for example, the 2019 volcanic eruption that happened in the Kingdom of Tonga, and which started 40 meters below the water level. Pieces of grey pumice, a porous rock loaded with gas bubbles, floated to the surface as a result, with the volcanic material eventually gathering into pumice "rafts" that covered a healthy few kilometers square of area, some of which were as huge as beach balls.

In general, debris produced from an initial eruption combines with material spewed during subsequent leakage of volcanic material, to produce a single large landmass. However, this landmass is usually at the mercy of the ocean, as the waves constantly try to erode it. If the magma source generates enough explosive deposits and lava flows to keep up with that erosion, the chances of survival go up, but that's not to say the island will automatically stick around. These floating islands, which are shaped and carried along by sea currents and winds, can travel great distances and also serve as a dispersal mode for organisms, as detailed in this research published in PLOS ONE.

Whether that will be the case with this newly-forming island still remains to be seen (or, for that matter, whether it'll have some unusual residents). According to MIT research, there are two primary factors which determine the longevity of a volcanic island. First, there's the speed of the movement of tectonic plates underneath it: fast-moving plates tend to result in shorter-lived islands. The size of the plume that created it, though, also plays a role, since the plate needs to slide across that swell.