Tesla's Biggest Challenge Is Batteries, And There's No Easy Fix

Suddenly, battery chemistry is the most interesting – and arguably most frustrating – topic in technology. Tesla's announcement today of a new, larger battery pack which will make its debut in even-faster versions of the Model S and Model X may sound like just another spec bump as the automaker looks to further eclipse gas engines, but according to CEO Elon Musk it's never been harder to improve range and performance.

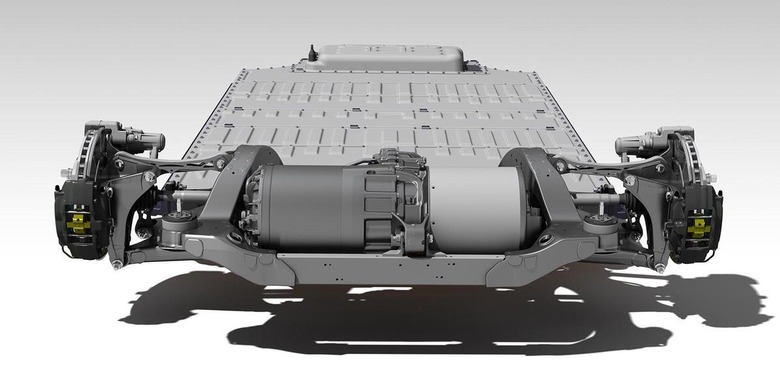

To the average car fan, the Tesla Model S P100D with Ludicrous mode (and its similarly potent SUV sibling) is simply another level of speed squeezed from instant-torque electric motors. The drivetrain of the Model S is actually identical to before; Tesla dropped in a more potent, 100 kWh battery to cut the sedan's 0-60 mph time to a mere 2.5 seconds.

That's legitimately fast, not just for an electric car. In fact, it makes the P100D in Ludicrous mode the third fastest production car, after two million-dollar coupes from Porsche and Ferrari.

Getting away from the lights in record time is fun, but most Tesla owners are probably salivating more at the 315 miles of EPA range promised from the larger battery. Getting more mileage on a single charge has always been the challenge for electric cars and plug-in hybrids, if they're not only to convincingly compete with traditional gas engines but minimize the investment required to roll out comprehensive charging infrastructure.

Problem is, battery chemistry and cell geometry are reaching a limit, something Elon Musk and his team know all too well.

"The difficulty of increasing the energy in the pack is truly non-linear with increasing the energy," Musk said today on a pre-announcement conference call about the new battery option. "Although it may be a 11- or 12-percent increase in capacity, it's really been a 50-percent increase in difficulty."

The concern is that Tesla is butting heads with limitations presented by battery technology itself. Indeed, the theoretical barrier to greater capacity with current cell systems is near, Musk predicts.

Nonetheless, the automaker's founder is still confident that a stride forward in battery technology is at hand.

"This is not the biggest pack we'll ever make – we can make bigger packs," Musk promised. "This was constrained to make three digits in the kilowatt levels but without fundamental improvements in the cell chemistry. But there will be cell chemistry improvements in future."

Indeed P100D Ludicrous buyers are playing an important part in that research, Musk pointed out, given that the "expensive car" they're ordering is helping pay for "learning more about the core technology."

Tesla will only produce around 200 of the 100 kWh battery packs per month initially, or approximately a tenth of its total production. The goal, of course, is to increase that number, but Musk says that fitting more power into the same chemistry is complex and that it'll take time to ramp up.

Not only is the bigger battery complex to make, it's expensive too. Tesla will charge a $10k premium on top of existing P90D Ludicrous orders to switch to the P100D Ludicrous instead, while those who have already taken delivery of their car can upgrade for a whopping $20k.

That has a significant impact on Tesla's aim to make more affordable EVs, firstly the Model 3. Expected to go into production in the latter half of 2017 – Musk declined to comment specifically on the car during today's call – it's set to be the cheapest member of the Tesla family, and has already racked up several hundred thousand reservations.

At the same time, Tesla's plans for Powerwall home batteries hinge on how much power each can store. With the typical US home consuming around 30 kWh per day, the new 100 kWh battery could effectively keep the entire household running for more than three solid days.

Currently, Tesla's domestic Powerwall is expected to offer 6.4 kWh, which is sufficient, the company says, "to power most homes during the evening using electricity generated by solar panels during the day." Multiple units can be daisy-chained for more capacity overall.

Before such a battery would be feasible for that kind of use-case, though, it would need to significantly come down in price. Tesla isn't the only company working on that, of course, but with the automaker betting its future on the advances in scale and R&D the upcoming Gigafactory is expected to bring online, it may be first in line to benefit.