After 20 Years, HTC Reveals How The Sausage Is Made

For a company whose tagline is "quietly brilliant", it's perhaps no surprise that it's taken some time for HTC to allow anyone behind the scenes of how its phones are designed and manufactured. That all changed this week, with two big milestones: the launch of the new HTC U11 flagship, and HTC's 20th anniversary. To mark the double-occasion, HTC invited media to Taipei, Taiwan, to see where the U11 was born.

HTC as we know it hasn't always been so forward with its brand. The company began as an original design manufacturer (ODM) and original equipment manufacturer (OEM), building notebooks, phones, and tablets that carriers and other firms would put their brand on. It was only in 2006 when the first HTC-branded phones were launched, the TyTN and MTeoR.

Since then, HTC carved itself a niche as the de-facto choice for early Android devices, then saw that prominence fade amid Samsung's meteoric rise. Although a loyal cohort of fans remain, not all of HTC's gambles have paid off: the Duo Camera of 2014's One M8 pre-empted the dual-cameras popular today, but struggled to explain to buyers why they should want it. The 20-megapixels of the One M9 the subsequent year went completely counter to the company's previous insistence on "quality not quantity" without delivering the visual goods in the process.

Sometimes, HTC's decisions have just seemed plain inscrutable. Now, it wants to explain exactly why the U11 is what it is.

Invited out to Taipei, HTC offered to take me around three of its previously off-limits facilities. First, the factory where the U11 is made; then, to the Design Studio where – in tandem with its San Francisco, CA facility – the smartphone was designed; and finally, to the Research & Development facility where its core competencies in audio and photography are developed and then put through their paces. It's the first time in two decades that anybody from the media has been taken on such a tour.

In each location, members of the on-site team talked us through each stage of the process. Unfortunately, HTC wasn't quite willing to let me loose with my camera: the photos you see here were provided by the company. The upshot to that is you don't have to see a picture of me in anti-static booties, coat, and hair net.

There's something hypnotic about a gadget production line. The U11 starts its life as a slab of substrate, onto which components are fed from reels like a monstrous Dymo label-printer. At one end, the smallest chips are fed in from rack-loaded spools; at the other, bales of Snapdragon 835 processors and gleaming SIM trays are among the largest items to be fitted.

Through a soldering tunnel, and then out into stacked trays, each board gets its turn in a brace of testing machines. Robot arms pluck them from their cushioned platters and feed them into equipment that assesses things like wireless radio tuning. The testing process is repeated periodically along the production line, the slowly assembling phone getting reviewed after each major stage.

From one robot-heavy floor, the completed boards meet up with the U11's frame, display, and battery on another level of the building. There, human workers sit along a creeping conveyor, either assembling parts themselves or slotting them into the machines that will do the same. It's a pragmatic process: if a human would be quicker, such as fitting in a single screw, then a human does the job. As soon as the task tips over a certain line, however – like screwing in four screws in a single plane – a robot is called upon.

Glue is squirted in, chassis parts come together, and then the finished devices are fed into a long tunnel where everything from WiFi and Bluetooth, through to LED flash performance, are put through their paces. More robot arms pick up handsets and drop them into testing boxes, Bluetooth connecting to a custom OS to run the U11 through its programs. Assuming they pass, a worker stacks them in a bay on a huge easel, where they're loaded with whatever localized version of Android their intended market demands.

Not all of the testing is left to the robots, mind. 10-percent of each batch of devices gets shunted into the human-staffed testing room, where workers replicate the common tasks users will attempt. Connecting to a WiFi network, setting up accounts, making calls, and using the charger are all put through their paces; 99.99-percent of the phones tested pass the roughly 40 minute long process. Only when they do, is the whole batch cleared for shipment.

It's a long way from the gleaming white marble of HTC's headquarters, where the company's Taipei Design Studio is found. It's a thoroughly modern building, too, designed to be LEED certified for its green credentials. At the top there's a green roof; underground, a huge water tank which holds rainwater from Taipei's periodic, heavy downpours and recycles it for use in the restrooms. A bank of gleaming glass elevators promise a third less energy use, thanks to the equivalent of regenerative braking when they're descending through the twenty floors.

In the studio, across an open atrium from the executive suites, two broad white tables are covered with a smorgasbord of HTC devices released and otherwise. There are plenty of One, Desire, and other lines in attendance, some recognizable as production phones, while others come in a rainbow of colors, samples that never got the green light to go into production. Teasingly, under each tabletop is a grid of broad, shallow drawers, within which hundreds of prototypes and design studies are lurking.

Only one is deemed safe enough to open, and inside there's HTC's never-produced play on the gaming phone concept. What looks at first glance like a Legend with a D-pad on its chin is actually a portrait-slider, opening out with a satisfying click to reveal joypad buttons. Why wasn't it made? That's not for the designers to say, though given the general failure of any attempts to make a gaming phone – Nokia N-Gage, anybody? – I can't really argue that it was a bad decision.

Still, the studio team is more interested in the U11's "Liquid Surface" design language. The product of several stages of heating, bending, and milling the Gorilla Glass 5 until complex 3D curves are created, it also uses Optical Spectrum Hybrid Deposition to layer refractive minerals across the back cover. As a result, each of the five colors – Amazing Silver, Sapphire Blue, Brilliant Black, Ice White, and Solar Red – have a shimmering depth depending on how the light catches them. HTC's silver, for instance, takes on ocean-like blue and teal green tones; its black borrows iridescent greens the designers say were inspired by the Aurora Borealis.

In contrast to the marble and open-plan layout, HTC's nearby Research & Development center feels more like a cube farm. Spread across a rented floor in building selected, the company tells me, for its proximity to a university, it's where the sound and camera teams ply their trade. Given media and photography are now among the top reasons buyers choose a device, it's an important part of the smartphone equation to get right.

It's also a hotbed of negotiation. Audio and camera may target different senses, but the one thing they have in common is that they each benefit from more space within your phone. That leads to a few fierce weeks of bartering between each team and the other engineers in the company, as they try to balance the "perfect" speaker assembly with whatever space can be liberated from circuitboards and battery.

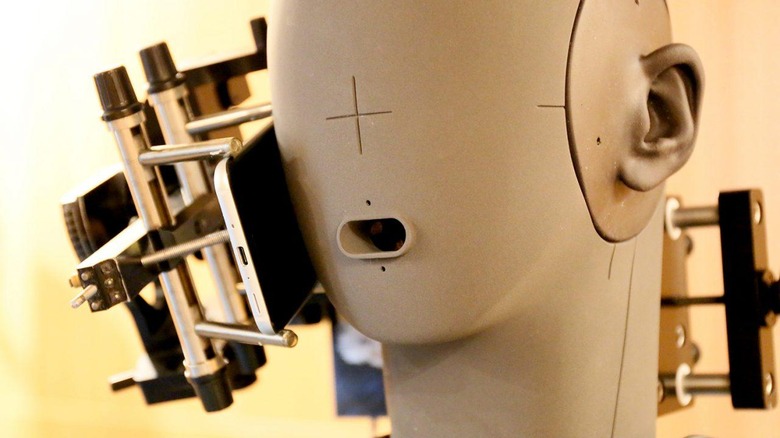

This year, it seems, the audio team has achieved something of a coup. The U11's speaker assembly is comparatively huge, a driver roughly half the footprint of a US postage stamp, and attached to a large reverberation chamber to give it sufficient lungs to warrant the HTC BoomSound HiFi label. An anechoic chamber – lined with echo-absorbing foam – sits alongside a listening chamber, each with a microphone- and speaker-stuffed dummy to test out features like the U11's active noise cancellation. That's a key justification for why HTC left out the 3.5mm headphone jack, since its bundled USB-C headphones now promise to make your next flight or coffee shop workday more peaceful.

Down the hall, the camera team dwells in a black-walled room that would make even the pickiest emo teen happy. There, the 12-megapixel camera on the U11 was tuned for auto-exposure, white balance, and color accuracy, HTC opting to skew the results to what the human eye might see rather than the chase the saturated hues some rivals prefer. Again, it's a balancing act between available space and the size of your pixels, though fans of optical image stabilization will be happy to hear that room for that was secured.

None of this is, in the grand scheme of smartphone design, particularly unusual. Apple, Samsung, LG, and all the others each go through their own testing and experimentation; each plays the human-robot hybrid game, attempting to coax out the maximum production efficiency by balancing the strengths of each worker. If there's anything new it's HTC's willingness to draw back the curtain on its process.

That's important, because the "black box" approach to smartphone design has done the company no real favors in recent years. Playing your cards close to your corporate chest might work if you're an OEM, building the devices your customers are requesting and making little comment on their virtues either way, but for a consumer-facing brand today there's much more of a dialog expected. If you take away my headphone jack, for instance, you damn well better explain to me why.

NOW READ: HTC U11 hands-on

The HTC U11 is shaping up to be a great phone; the most well-rounded the company has produced in some time, indeed. Yet what has hurt HTC in the past hasn't so much been the decisions it makes about its devices, per se, but the way it communicates those decisions. A modern smartphone can't exist in isolation, it needs to be part of a story, an ecosystem, which a user can buy into. At this most precarious point in HTC's two decades, the time for quiet brilliance is past: now it needs to make its story heard.