3D-Printed Living Ear Transplanted To Girl Born Without One

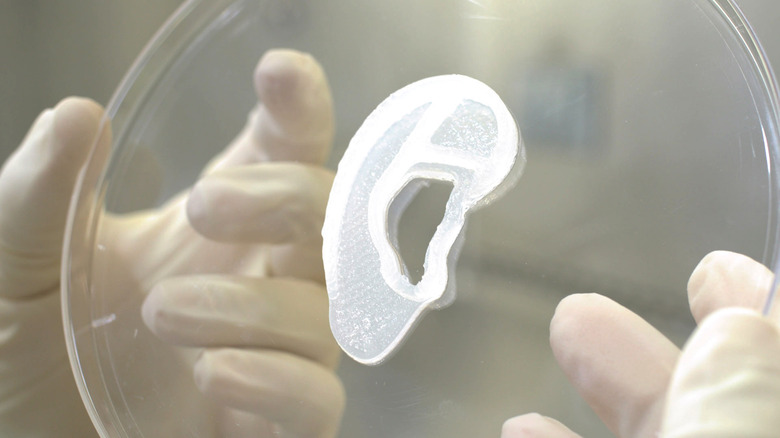

The technology to utilize 3D printing technology to create replacement body parts for transplanting has been around for at least half a decade, complete with an aim to provide people with reconstructive options that aren't limited to prostheses. Before now, 3D printing body parts was a relatively basic process and resulted in products that had some significant limitations. This is why 3DBio Therapeutics successfully grafting a 3D-printed ear – an implant it calls "AuriNovo" — onto a patient is kind of a big deal.

But there's more to it than that. Not only has 3DBio started human grafting tests with 3D-printed biological implants — it's also created the implant using the patient's own cells. By using cells taken from the patient's own ear cartilage, this new type of transplant could result in more compatible implants that require far less invasive surgery to gather the initial cells. Clinical trials are still in progress, so whether or not this would be a definitive improvement has yet to be determined.

The 3D-printed ear you see above is intended for a patient afflicted with a rare congenital condition known as microtia, which prevents one or both ears from fully forming. The 20-year-old woman who has become the first recipient of an AuriNovo implant was born with an under-developed right ear. Her new implant will need some reshaping via follow-up surgeries, which is common with similar implants, but the team is hoping to expand human trials to include more patients between the ages of six and 25 over the course of a study taking place this year.

Why 3D-print ear cartilage?

Current ear implanting techniques use synthetic materials or rib cartilage for construction, and both techniques have a list of potential caveats. As suggested by 3DBio, artificial implants are rigid, "do not feel like human ears," and can shatter on impact. Synthetic implants work with a process that's less invasive to the patient than working with rib cartilage, but they do still require a fair bit of skin grafting from the scalp, carry a risk of infection due to non-biological materials, and can change color or shift position over time.

They also suggest that rib cartilage ear reconstructions are rigid, "do not feel like human ears," and can be uncomfortable. While harvesting cartilage from a patient for an implant greatly reduces the chances the final ear graft will be rejected by the body, taking the cells from ribs is an involved process. Current techniques require two separate procedures that can each take several hours. This process requires the harvest of material from at least three separate ribs and can result in chest deformity.

AuriNovo implants are created by first collecting cartilage cells from the patient's ear, cultivating those cells to create printing materials, then finally printing an implant that's designed to look and feel like the patient's other, fully-developed ear. When and if it's approved for regular use, the process is expected to work with an outpatient procedure so anyone receiving the implant wouldn't need to stay in the hospital overnight (which is both less stressful and cheaper than current alternatives). Additionally, the softer and more natural feel would make the implant more comfortable and less susceptible to damage from external forces.