Magnetic Cloaking Device Shows The Tech Is No Longer Science Fiction

Scientists have been trying to create real-world invisibility cloaks for years and have even demonstrated some promising breakthroughs in the process. However, that's not the only cloaking scientists are trying to achieve. Protecting (or "cloaking") sophisticated instruments and electronic objects from magnetic fields, which can cause electronic devices to malfunction, has long been a goal for scientists, and it seems that a breakthrough has finally arrived.

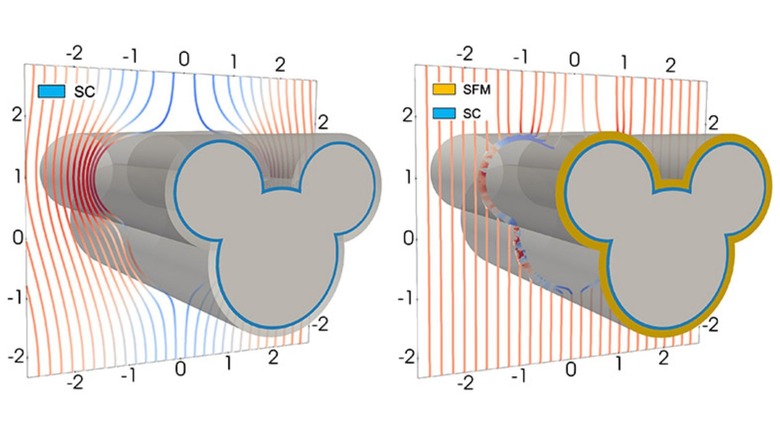

In December 2025, engineers at the University of Leicester announced a concept for a cloaking system that can make any object appear invisible to surrounding magnetic fields. The findings, published in Science, mark the first time that the design of a magnetic cloaking device has been practically demonstrated for real objects. So far, the idea has remained stuck in the realm of theoretical science, with the cloaking limited to specific shapes. Conversely, the University of Leicester team claims that its technique facilitates magnetic cloaks for objects of any shape. Moreover, the cloak can handle surroundings with a wide range of magnetic field strengths.

In a press release, Dr. Harold Ruiz, one of the study's authors, claims that it "shows that practical, manufacturable cloaks for complex geometries are within reach, enabling next-generation shielding solutions for science, medicine, and industry." It's worth noting that the magnetic cloak research only covers the process of making these devices. But now that the method has been validated, the team plans to make an actual magnetic cloak and test it in a real-world setting. In the research paper, the team also notes that its method can significantly reduce costs associated with magnetic cloaking, as well.

A versatile breakhthtough

The team proposes using a commercially available high-temperature superconducting tape, with an outer shell consisting of a nickel and zinc mix with epoxy resin to achieve a flexible shape. By adjusting the ratio of nickel and zinc in the powder, the team says it can adjust the magnetic permeability of the cloak. There are, however, technical hurdles. First, manufacturing a magnetic cloak based on the method described is itself a pretty challenging task. Second, the magnetic cloaking is not universal, as it depends on the direction of the magnetic field falling on the object that needs to be covered.

If the geometry changes or a rotating magnetic field is involved, the entire apparatus would require adjustment. Most importantly, since the magnetic cloak involves the usage of superconducting materials, the temperature of the entire application area must be kept low. While this could be an issue, the team is confident that the cryogenics industry is developed enough to support the cloak's use. Once the inherent challenges are overcome, the team believes that its magnetic cloak could find rapid adoption in situations with instruments that are notoriously sensitive to any kind of external magnetic interference, such as scientific labs and hospitals. Protection against magnetic fields would be an extra layer of defense for the latter, alongside the red power outlets that supply backup power.