Here's How Planes Can Fire Bullets Through Propellers Without Destroying Them

The Wright brothers made history on December 17, 1903, when they took to the air in their "Wright Flyer." Six years later, they sold the world's first military plane (aptly named the Wright Military Flyer) to the Army for $30,000. The evolution of the warplane was rapid, and it didn't take long to realize the most accurate place to mount front-firing machine guns was on the airframe, directly in line with the aircraft's flight path.

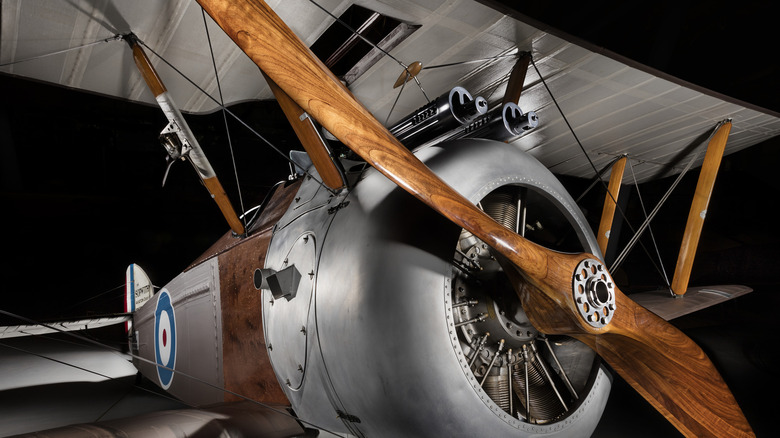

Because their accuracy relied entirely on the pilot acquiring a target manually (no fancy targeting computers for them), the best place to put them was directly behind the propeller. At the time, this was a very challenging problem to solve because the rates at which propellers spun and guns fired fluctuated considerably. They somehow needed to be synchronized to miss each other entirely during their deadly dance. Early attempts at fixing this problem began in France and Germany in 1913 and 1914.

While some used crude mechanical hydraulic devices, others tried to make the propeller blades bulletproof by attaching armored steel plates that would deflect bullets. In the Spring of 1915, Dutch engineer Anthony Fokker custom-built a single-seat monoplane (the Fokker Eindecker) for the German Air Service, which featured a fully functional synchronization gear that, in effect, made the propeller shoot the gun instead of the pilot. This innovation immediately gave the Germans the upper hand in the air so overwhelmingly that the summer of 1915 became known as the "Fokker Scourge."

Timing is, quite literally -- everything

Fokker, whose name is synonymous with warplanes, knew that the Parabellum machine gun shot 600 rounds a minute, and the plane's two-bladed propellers spun 1,200 times a minute, meaning a single blade passed a given point 2,400 times every minute. His synchronization gear system was rather simple, but first needed the pilot to activate it before firing a single bullet.

A small knob attached to the propeller struck a cam wheel connected to the propeller shaft — that was actually communicating the propeller's spin rate as it turned. A knee lever in the cockpit allowed the pilot to engage a spring-held pushrod, a part of which was hinged to strike the machine gun's hammer, and fire away. Testing at slower speeds showed that a single blade-mounted cam allowed the bullets to pass through the arc of the propeller without hitting the blades. The entire system would shut down immediately if the engine stopped.

By the summer of 1916, both British and French air forces had designed their own versions of this synchronization gear (sometimes referred to as the interrupter gear). In 1917, Romanian engineer George Constantinesco was working with the Allies and knew that mechanical gears had limitations. He developed the Constantinesco Fire Control Gear (or CC gear) using a more reliable hydraulic system. Within a year, the CC gear was installed on more than 6,000 British planes. By 1930, technology had advanced to the point that most fighters were equipped with a pair of synchronized machine guns that used an electrical timing system.