Do Captains Really Go Down With Their Ships? The History Behind The Tradition

Maritime history dates back to the very dawn of humanity, with some scientific circles suggesting we've been sailing the high seas since the late part of the Early Pleistocene, roughly 900,000 years ago. The idea that the captain must go down with their sinking ship, however, is a tradition that seems to have arisen sometime during the 19th century and reflected Victorian chivalry of the day, where honor-bound duty collided with a moral obligation to take care of not just the ship and its cargo, but the safety and well-being of every last soul on board.

Interestingly, there are no laws that state a captain must die with his ship. However, international law stipulates that captains must adhere to the principles of prudent seamanship and ensure the safety of both passengers and crew. Legal requirements for a captain were first established at the Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS) convention in 1914 as a result of the Titanic tragedy. That evolved into the International Maritime Organization, an agency within the United Nations responsible for developing international shipping laws and maintaining the safety and security of maritime traffic. It currently has 176 members (the United States joined in 1950).

Other countries with much longer seafaring histories (i.e., Spain, Greece, Italy, Finland) have laws that require the captain to be the last person to remain onboard, ensuring that passengers and crew have evacuated safely and that every attempt was made to save the ship. Despite no requirement to make the ultimate sacrifice, many have, which has most certainly given way to the many stories of ghost ships still sailing around the globe.

Women and children first

For centuries, it was common for a captain to be the owner of their ship and thus wielded the ultimate authority, but also bore the ultimate responsibility. The vessel was often the captain's home and contained everything they owned. In a catastrophe, fighting until their last breath was a better alternative than certain financial ruin and possibly even criminal prosecution. As such, captains were assuredly going down with their ships long before the 19th century.

However, the concept was forever seared into our modern psyche on April 14, 1912, when the Titanic hit an iceberg and sank (something that can still happen today). The disaster took the lives of some 1,500 people, including Captain Edward Smith. According to accounts, he too went down with the ship and was applauded for not only taking care of his passengers first, especially the women and children, but for his "willingness to die."

The origin of the "women and children first" dates back to a 1852 maritime disaster. The HMS Birkenhead, a British paddle-wheeled steam troopship, was sailing around the Cape of Good Hope, South Africa, when it hit some rocks and began to sink. Of the approximately 640 officers and soldiers — as well as numerous wives and children — aboard (the exact number varies), only 193 survived. Captain Salmond went down with the ship, yet all of the women and children survived because the men prioritized their safety. Their act of heroism went viral (or at least the 1800's equivalent of viral) and from it evolved the still-used "Birkenhead Drill," where women and children are evacuated first — a practice Captain Smith surely followed on the Titanic.

Salvage laws played a part in making the ultimate sacrifice

Another facet of this last-man-standing tradition comes from salvage laws. Professor Rod Sullivan, who teaches maritime law at the Florida Coastal School of Law, told NPR, "This has never been the idea that the captain is so married to the vessel that if the vessel dies he should die." Instead, it centers on the fact that the moment a captain abandons the vessel, "anybody can come onboard" and legally salvage the wreck (and whatever treasures it may hold) for themselves.

In a display of this very notion, on September 12, 1857, Captain Herndon went down with the SS Central America off Cape Hatteras during a bad storm. The ship was carrying 575 people (many of which were women and children) as well as $2,000,000 worth of gold. According to sources, all of the women and children were rescued before it sank, likely following the "Birkenhead Drill" which had been established some five years before.

Unfortunately, Captain Herndon did not survive, but his final acts as captain are legendary. Much like a scene cut from a movie, he handed his watch to a passenger to then give to his wife as a posthumous token of his love. He then reportedly went back to his stateroom, put on his uniform, and proceeded to the wheelhouse. As the SS Central America began to slide under the waves, he reportedly warned an approaching rescue boat not to come any closer or they'd get taken under as well, raised his hat in a farewell salute and went down with the ship.

Not all captains can be brave

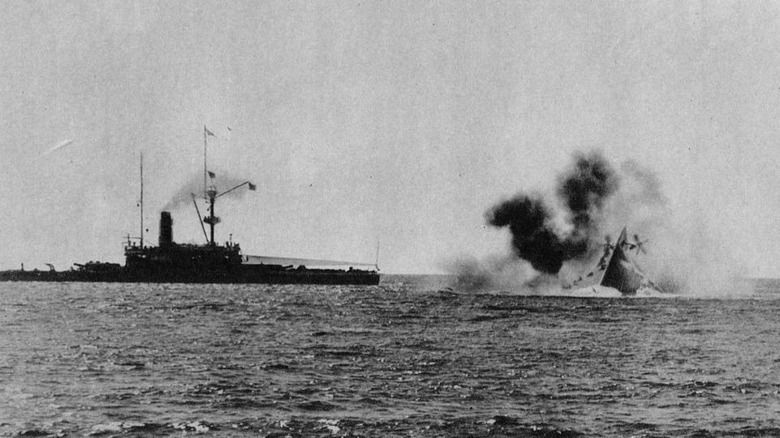

In 1893, two British battleships — HMS Victoria and HMS Camperdown — were conducting tactical exercises off the coast of Tripoli, Lebanon. In an attempt to prove the fleet could conduct a tactical reversal, Admiral Sir George Tryon ordered the two columns of ships following the Victoria and Camperdown to turn inward towards each other, but without first having the proper turning radius distance between them.

Keep in mind, this was before the radio was invented, and ships communicated via semaphore (visual signals using flags, arms, and/or lights). Unfortunately, the Camperdown sliced through and sank the Victoria, killing more than 350 sailors, including Tryon, who by all accounts was last seen on the bridge of the Victoria as it went under. His final words were reportedly, "It is entirely my fault."

Then we have Captain Francesco Schettino and the Costa Concordia disaster in January 2012. As the ship passed the island of Giglio, it hit a reef called Scole Rocks and began to sink. Before all 4,229 people aboard were evacuated, Schettino jumped onto a lifeboat, where he claimed he was orchestrating the evacuation. That didn't hold up in court because under Article 1097 of Italy's Maritime Law, the captain must be the last to leave. Furthermore, it was later discovered that the ship had sailed too close to the island at high speed (15.5 knots). Thirty-two people died and Schettino's prison sentence of 16 years included one year for abandoning the boat far too early. So much for chivalry.