How The US Tested Nuclear Weapons (And Why It Became Too Dangerous To Continue)

For better or worse, the U.S. nuclear arsenal is currently having a moment. First, "A House of Dynamite" became an instant No. 1 hit for Netflix shortly after its global streaming debut in October. The film, directed by Oscar-winning filmmaker Kathryn Bigelow, quickly gained buzz for its chilling depiction of how the U.S. military and government could respond to a surprise nuclear attack. Then, soon after the release, President Trump announced plans to begin testing nuclear weapons (in real life). This announcement followed recent tests of nuclear-powered weapons by Russia, but still came as a shock to many, because the U.S. hasn't tested a single nuclear weapon since 1992.

That's 33 years — five entire presidential administrations — of no nuclear testing, which came after decades of detonating powerful nuclear bombs to test energy output, blast range, thermal and electromagnetic effects, radioactive fallout, and more. Famously, the first nuclear test — by the U.S. or any other nation — was Trinity, conducted in New Mexico on July 16, 1945. It was part of the Manhattan Project, led by J. Robert Oppenheimer and General Leslie Groves, and led to the use of atomic bombs on Japan to end World War II less than a month later.

To date, it's the only time nuclear weapons have been used in armed conflict. However, the U.S. and other nations had detonated thousands of nukes since then as part of scientific and military tests. For its part, the U.S. conducted these tests far from densely populated areas. Many took place in the American Southwest, with Nevada eventually becoming the most nuked place on Earth. Many others were conducted over the Pacific Ocean, including near the Bikini Atoll.

Most U.S. nuclear tests were conducted underground

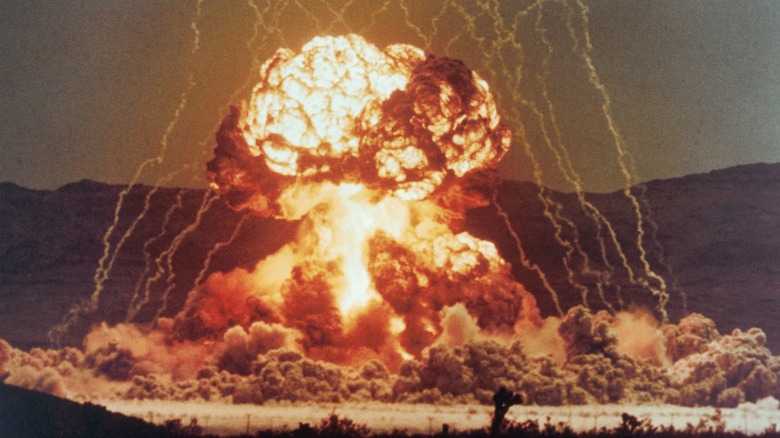

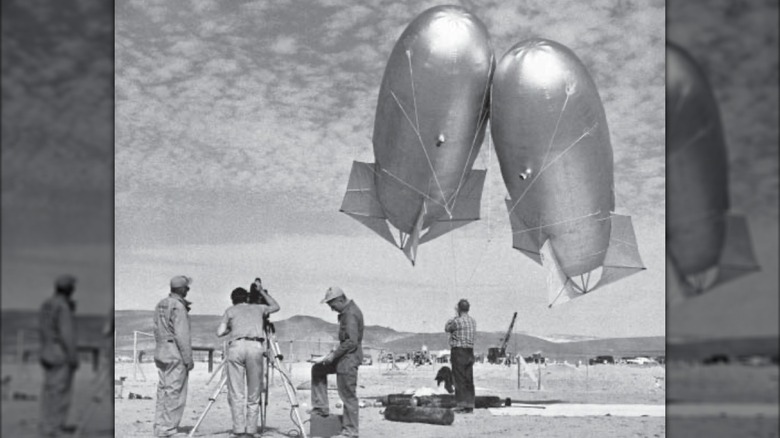

After World War II, only five nuclear tests were carried out by the U.S. between 1946 and 1948, with 16 more occurring in 1951 as the technology and ability to mass-produce atomic weapons advanced. By the time the U.S. ceased all testing in 1992, the nation had conducted 1,054 nuclear tests. Some of these, especially early on, were similar to Trinity — detonating a bomb suspended from a 100-foot tower — while others were set just a few feet off the ground. Others were detonated on barges or tied to balloons to explode high in the air. Many nuclear bombs were dropped from aircraft and detonated as airbursts.

As the U.S. continued to test its weaponry, it explored other methods, including undersea and low-Earth orbit detonations, to see what happens when a nuclear bomb detonates in space. The latter test, Starfish Prime, occurred 250 miles above the Pacific Ocean. For comparison, the International Space Station (ISS) orbits at the same height. In an effort to reduce radioactive fallout from being released into the atmosphere (more on this later), the U.S. transitioned to underground nuclear testing. In 1963, the nation signed the Limited Test Ban Treaty (LTBT) with the Soviet Union, which prohibited above-ground nuclear tests.

As such, all testing between 1963 and 1992 — the vast majority of U.S. nuclear detonations — was underground, occurring at sites in Nevada, New Mexico, Colorado, Alaska, and Mississippi. Shortly after the Cold War ended, President George H.W. Bush enacted a moratorium on nuclear testing, which President Bill Clinton extended indefinitely with the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty (CTBT) in 1996. The final U.S. test of nuclear weapons was conducted in Nevada in 1992.

Radioactive fallout from nuclear tests is everywhere

Along with the hopes of de-escalating tensions with other nuclear powers, the testing ban that began in 1992 was enacted for the same reason testing transitioned underground in the 1960s — to avoid the danger of radioactive fallout. Nuclear detonations release radioactive particles, which cling to dust, water droplets, and other fine debris. The half-life of these particles — the time it takes to stop being radioactive — can range from days to decades.

Smaller radioactive particles from nuclear tests are light enough to be carried far from testing sites by wind or water. Some even enter the upper atmosphere and spread globally. Radioactive particles can be absorbed in many different ways. For example, if they fall into the soil, they can continue to be found in the grass that grows from that soil, which then enters the cows that eat that grass, before ending up in the cows' milk that we drink. Radioactive particles from that milk can then collect in our thyroid glands. Extensive research has found that fallout radiation is also absorbed by organs, tissues, and especially by bone marrow. Because they can disrupt and damage DNA, radioactive fallout can greatly increase the risk of cancer to anyone exposed.

Radiation from the hundreds of nuclear tests conducted in the 20th century can be found all over the globe, with thousands of cases of cancer attributed to it, hundreds of which have been fatal. Testing-related radioactive particles have been found within inhabitants of every state in the continental U.S. Other than the fact that nuclear testing inevitably escalates the threat and tension of actual nuclear warfare (as well as potential military accidents involving nuclear weapons), this fallout is one of the reasons officials previously deemed nuclear tests too dangerous to continue.