The Adams-Farwell Was A Terrifying & Strange Engine - Here's Why

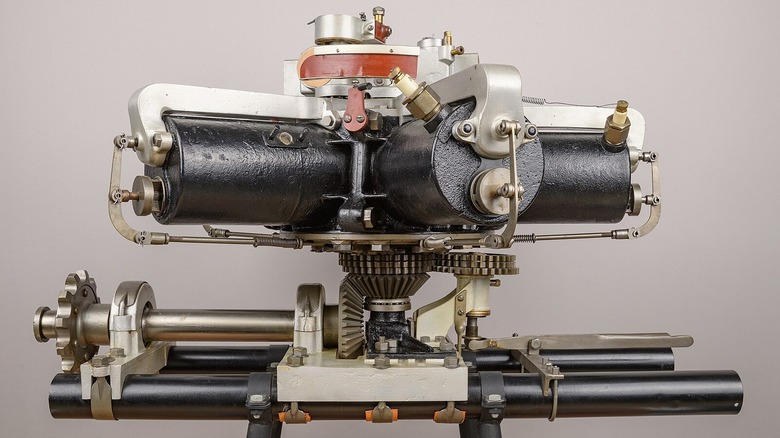

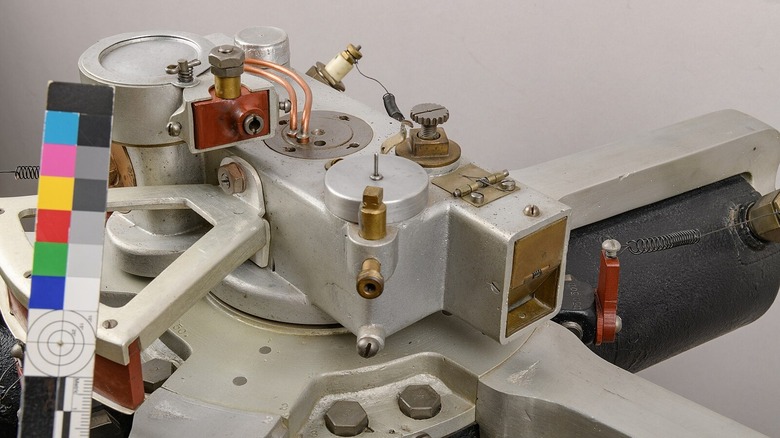

Just on the cusp of the 19th century, the first ever rotary engine appeared from the budding automobile manufacturer, the Adams Company. The Adams-Farwell engine was both inspiringly inventive and a bit unsettling. While modern engines have many moving parts, these movements are housed within the engine block. In contrast, the Adams-Farwell rotary engine looks more like a horizontally mounted windmill, with the cylinder housings spinning around within the engine compartment. Different variations consisted of three- and five-cylinder builds that transformed the automobile's powerplant into a 190-pound whirling iron top. When installed in vehicles, these engines were typically situated in the rear rather than the front of a car.

Only one Adams-Farwell automobile with a working rotary engine is still around. However, that doesn't mean the concept of a rotary engine disappeared. The Wankel rotary engine, which uses a different design featuring a triangular piston, was incorporated into some of the best cars ever built with rotary engines, which are known for making a unique "brap brap" sound. However, the Adams-Farwell engine's bizarre build was unique, and it's something that enthusiasts still marvel at.

The Adams-Farwell engine worked differently than modern engines

Modern engines use a specialized coolant liquid to help reduce rising temperatures that could potentially damage the car. Years before coolant started to be commercially used, the Adams-Farwell was designed with a way to cool itself on its own. The cylinder housings or "jugs," which spun around during operation, included fins which could efficiently dissipate heat into the air. This is similar to how some motorcycle engines utilize air to reduce temperature. In fact, the faster you drove the Adams-Farwell car, the faster the piston "jugs" would spin, making sure the engine didn't overheat.

In addition to the way it cooled itself, the Adams-Farwell engine also worked differently than modern engines in the way that it converted fuel to power. When a driver pushes the accelerator pedal in a vehicle with a contemporary gasoline engine, they open the throttle valve, which controls how much air goes into the engine and in turn how much fuel flows into the system. The Adams-Farwell used a compression system instead. That means that when the driver pressed the pedal in a vehicle with one of these engines, they controlled how much pressure was transferred into the next cylinder via intake valves.

The Adams-Farwell did have disadvantages but was tested in aircraft

Centrifugal force is a term used to describe an outward pressure felt by an object spinning in a circle. This is why you may feel like you are being pushed away from the center of a merry-go-round on a playground, with it becoming more challenging to hold on the faster you get it spinning. Centrifugal force also starts to influence the way the Adams-Farwell engine works when it gets going fast enough. Essentially, efficiency is reduced because the cylinders need to work harder to complete each stroke against an increasing outward push of force.

Nevertheless, people were interested in using it in the early 20th century. In 1909, an aircraft envisioned by Emile Berliner and J. Newton Williams that was equipped with two of these unique rotary engines was able to sustain a promising short lift off the ground. Ultimately, another rotary design called the Gnome engine outperformed the Adams-Farwell, though, and the Gnome N-9 would become one of the groundbreaking engines that changed the face of warfare.