What Happens To A Heat-Seeking Missile If It Loses Lock And Misses Its Target?

In 1956, the United States Navy received one of the first and most successful air-to-air missiles ever made, the AAM-N-7 Sidewinder (now called the AIM-9 Sidewinder). The Sidewinder has been in service ever since, and is a reliable, relatively inexpensive, and lethal short-range air-to-air missile. The weapon uses thermal radiation to lock onto and strike its targets, making it the first operational "heat-seeking" missile ever made.

These missiles are the reason fighter jets shoot flares to avoid being hit in the desperate hope they will lose their targeting lock. The missiles work by using their sensors to find a significant source of heat, and despite being the hottest thing in the solar system, modern heat-seeking missiles avoid locking onto the sun. Their targeting systems are highly complex feats of technological engineering that ensure they lock onto the target designated by the pilot. Of course, like any missile, the Sidewinder and other heat-seeking air-to-air missiles can lose their target lock and miss. So what happens when this occurs?

It's a fair question because some might assume it would turn around and hit the plane that fired it. While this is theoretically possible, there's no recorded incident of a plane shooting itself down with its own missile — bullets, yes, but not a heat-seeking missile. When a heat-seeking missile like the Sidewinder loses its lock or misses its target, all is not lost. The missile won't fly into a home or passenger aircraft because it's outfitted with a timed fuze and the ability to self-destruct after a set period of time.

The firing, locking, and striking process of a heat-seeking missile

Continuing with the Sidewinder as an example, the process of finding a target, achieving a lock, and firing the missile depends on several factors. The Sidewinder can be fired without a radar lock, so it's up to the pilot how they want to fire the missile. The seeker can accurately and quickly find and lock onto a target, which it signifies via a tone. Once the firing solution is obtained, the pilot launches their AIM-9, announcing their callsign and saying "Fox Two" over the radio to signify that they're firing an infrared homing missile.

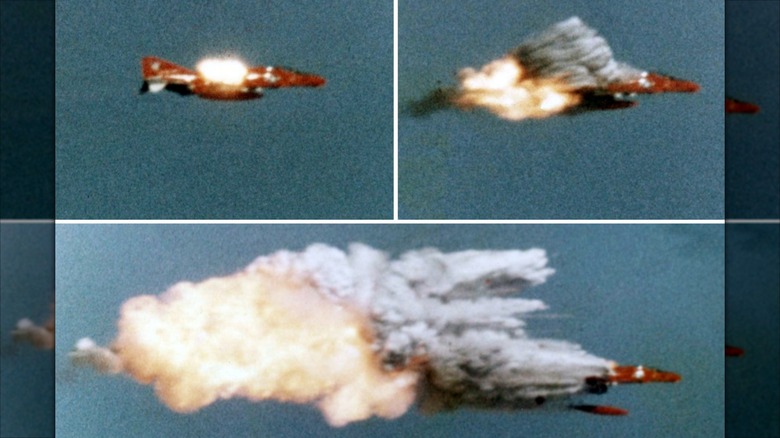

Modern variants of the Sidewinder have more accurate sensors and targeting capabilities than the original design. They don't necessarily have to lock onto a jet's exhaust or be fired in their direction, and can instead locate the heated air friction the aircraft generates while moving through the sky. Whatever it locks onto, the missile will maintain that lock until it strikes the target or loses its lock and misses. When this happens, the missile attempts to reacquire its target. If this effort fails before the timed fuze expires, the missile self-destructs, reducing the risk of hitting an unintentional target.

If the missile doesn't come close enough to detonate via its proximity fuze, the warhead explodes, taking itself out, which occurs after around 24 seconds. The missile can miss, but get within range to detonate its warhead in a near miss, so a self-detonation can potentially take out a target. Despite the potential for missing, Sidewinders have a long track record of success in combat, which is one of the reasons they remain in service today.