How Polygraph Tests Work (And Can They Really Tell If You're Lying?)

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) has found itself embroiled in a rather odd situation involving polygraph tests. In April, it confirmed to NPR that it was using these tests to catch personnel who were potentially leaking information to the press. However, the situation took an interesting turn in July, when The New York Times revealed that the FBI had also conducted tests to check if employees had made any negative statements about FBI Director Kash Patel.

Contrary to their depiction in entertainment media and books, polygraph, aka lie detector, tests are not a foolproof method of assessing whether a person is lying. Instead, they merely measure the body's response to psychological stress and use it to get a rough estimation. For example, if the heartbeat accelerates and a person starts sweating at a certain set of questions, there's a chance that their responses may not be truthful. But over the years, it has been proven that lie detectors can be fooled, even brain lie detectors that are supposedly nearly unbeatable.

In 1985, Mark William Hofmann passed a lie detector test and later revealed how he tricked the biosensor-based system. While locked up in the Utah State Prison, the murderer told Dr. Charles Honts that he practised hypnosis and biofeedback control for 15 years. In 2021, Netflix released a documentary series titled "Murder Among the Mormons," covering Hofmann's life, including an episode focused on how Hofmann passed his lie detector test.

How do polygraph machines work?

At the most basic level, a polygraph machine detects changes in body functions. Think of stress signals, which are identified by a sudden spike in the heart rate or blood pressure, faster respiration, and sweating. It's not too different from the stress warning system on smart rings and watches.

The first ink-based polygraph that measured heart rate activity was developed by Dr. James Mackenzie over a century ago. It had two rubber-based ends that attached to veins on the neck and wrist, while a needle-based ink arm drew the signals they recorded onto paper. In 1921, a medical officer named John Larson, working for the Berkeley Police Department, developed the first lie detector machine that measured blood pressure as well as respiration. Around the same time, Leonarde Keeler developed a version that measured changes in skin resistance. This was based on the idea that a lying person sweats, and that the sweat changes the electrical properties of the skin.

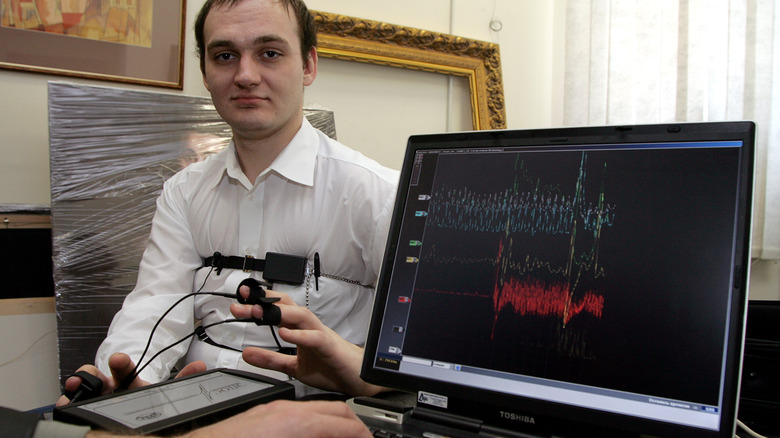

A typical modern polygraph or lie detector machine primarily measures heart rate, blood pressure, respiration, and skin conductivity changes. It features pneumographs strapped to the chest for tracking heart rate and respiratory depth, an arm cuff to measure blood pressure, and electrodes on the fingertips that track the changes in electrical responses generated on the skin. When it comes to the questions, criminal investigations usually follow a format called the Comparison Question Test (CQT). Another format is the Guilty Knowledge Test (GKT).

How reliable are lie detector tests?

Before a polygraph, a series of pre-training questions is asked to make the subject feel more comfortable. The idea is that compared to a "less risky" question, a person will respond more strongly to a direct or relevant question. Questioning also plays on secret knowledge that only a guilty party would know, such as a hiding spot, the nature of a crime, a specific date, or the exact time of events.

As far as cheating goes, lie detector machines can be tricked. Russell Tice, a National Security Agency (NSA) whistleblower who exposed government wiretapping, claimed that beating polygraph tests was very easy. One of the tricks involves biting the tongue hard, which triggers a physiological response for even the easiest question, throwing the evaluation into disarray. Systems like EyDetect hope to avert those failures by measuring eye movement.

Experts have raised concerns about the trustworthiness of polygraph tests. "An honest person may be nervous when answering truthfully, and a dishonest person may be non-anxious," says the American Psychological Association (APA). "The idea that we can detect a person's veracity by monitoring psychophysiological changes is more myth than reality," it adds.

Similarly, a committee that included experts from the U.S. National Academy of Sciences, the National Academy of Engineering, and the Institute of Medicine concluded that there is "little basis for the expectation that a polygraph test could have extremely high accuracy." Notably, the Employee Polygraph Protection Act prohibits companies from using these tests to screen employees.