Who Made The Tires For The First Lunar Rover And What Were They Made Of?

When President John F. Kennedy announced his intention to send a man to the moon in 1961, he kicked off a space race that would push America to the pinnacle of scientific discovery. While several technological leaps made the Apollo missions successful, one innovation may surprise you with its inventiveness: the (re)invention of the wheel.

After landing on the moon, NASA faced an equally challenging question: how to meaningfully explore the moon they'd spent seven years and $25.8 billion (roughly $318 billion in 2025 when adjusted for inflation) to reach. While putting a man on the moon was undoubtedly valuable from a sociopolitical perspective, to maximize the scientific benefits of the Apollo program, NASA needed to find a way to safely and effectively explore it. The problem? Low gravity, adverse conditions, and clunky hardware made traversing the surface by foot inefficient and dangerous. Worsening the problem was that the most scientifically significant locations on the moon were also the most difficult landing spots.

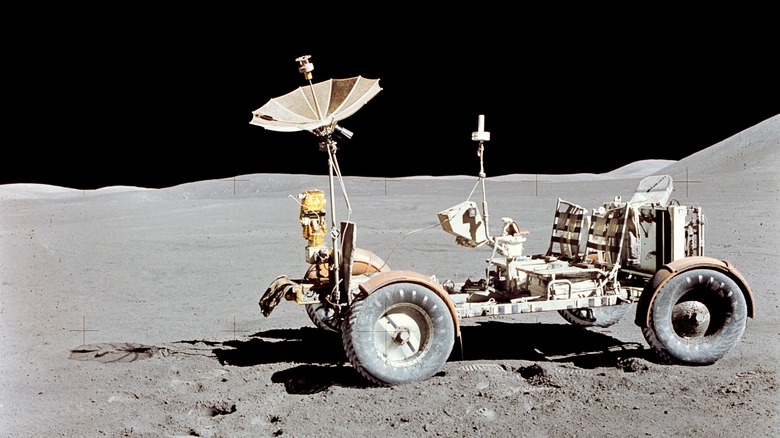

In 1969, NASA, encouraged by engineers at General Motors' defense research arm, solved this problem by instructing its Marshall Space Flight Center to design the first Lunar Rover Vehicle. Unfortunately, General Motors' prototypes were built without an understanding of the moon's surface – a major hurdle, particularly when designing the vehicles' tires. But as the first few Apollo missions filled in the blanks, Boeing, with General Motors as its subcontractor, delivered what many thought was impossible: a foldable vehicle sporting zinc-laced steel mesh piano wire wheels with titanium tread that could be transported inside the spacecraft. Debuted over 50 years ago during the groundbreaking NASA mission Apollo 15, the Lunar Rover's ingenious wheel design is almost as impressive as the Apollo missions themselves and paved the way for technologies like NASA's latest Lunar Rover, Viper.

Problems of traversing the moon

For the first four Apollo lunar missions, exploration was limited. At the time, a safe walking distance was less than a mile from the landing site. Furthermore, movement along the surface was extremely slow: low gravity levels forced astronauts to hop rather than walk, while spacesuits' limited mobility prevented them from moving their arms. As such, despite lasting 2 hours and 31 minutes, the first moonwalk saw Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin venture roughly 180 feet each. Logistically, this meant that the Apollo 11 mission traveled nearly 240,000 miles to collectively walk the length of a football field. Talk about small steps for man. Subsequent missions didn't venture much farther. According to NASA, the average speed of the 12 astronauts who ventured across the moon's surface during the Apollo missions was a glacial 1.4 miles per hour — a rate that would take 206 days.

To solve this issue, Boeing and General Motors built the Lunar Roving Vehicle at NASA's Marshall Center labs. In constructing the vehicles, engineers had to meet a strict list of standards, including weighing less than 450 pounds, featuring video and radio communication systems, and the ability to withstand over 250 degrees. After an intensive design process featuring 32 major tests across 13 months, the team delivered a fully electric lunar rover just in time for the July 26, 1971 Apollo 15 mission. With a foldable aluminum alloy chassis capable of handling over twice its weight, the two-passenger rover resembled a buggy more than a spaceship, replete with aluminum floor panels, armrests, adjustable footrests, Velcro seatbelts, and two 36-volt zinc batteries.But the rover's most innovative feature was its wheels, crafted bespoke by Boeing and GM for the unique challenges posed by the moon's surface.

Wheeling around

The moon's surface posed several challenges for GM and Boeing when designing the Lunar Rover's wheel system. With a surface temperature range of 500 degrees Fahrenheit, abnormally soft soil, extremely low gravity, and an uncertain topographical makeup, the Lunar Rover had to overcome problems not encountered by previous vehicles.

Set on a seven-foot aluminum wheel hub, the Lunar Rover's tires were fashioned from a mesh of zinc-coated steel piano wire, each strand of which was roughly 0.03 inches in diameter. Titanium chevrons ran down the length of the tire to enhance traction and prevent sinking, while dust guards, a bump stop frame, and epoxy-impregnated fiberglass fenders protect the integrity of the tire as it moves along the moon's surface. Each wheel was connected to one of GM's DC-series electric drives by a harmonic drive, each of which could ratchet up to 10,000 rpm. Front and rear steering motors made the Lunar Rover highly maneuverable. Astronauts used a T-shaped hand controller to direct this four-wheel drive, while advanced navigation features — including a manual sun-shadow tool — guided the vehicle to target areas.

On its first trip to the moon, the Apollo 15 astronauts used the Lunar Rover to conduct three different ventures traversing roughly 15 miles of moonscape while conducting experiments and collecting invaluable samples. For the most part, the vehicle performed without a hitch and was subsequently used on the subsequent two missions of the Apollo program. Overall, the Lunar Rover program utilized its ingenious wheel design to overcome one of the most pressing scientific questions of the modern age.