What To Know About Thin Film Solar Panels

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

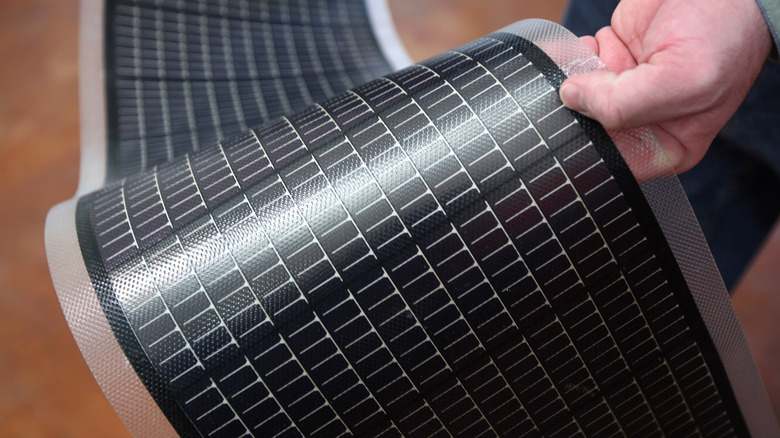

As the name implies, thin film solar panels are composed of solar cells that are much thinner than what you'll find in your average solar panel. To the point where, in most cases, they can quite literally flex and bend without breaking — though not so much if they're attached to rigid materials like glass or metal.

Thin film solar panels are also much lighter than more traditional style (i.e. rigid) panels and are comparably easier to install. They might not be the best idea for powering an entire home (we'll get to that), but they work well with RVs, sheds, and so on. Basically if something is too small or not sturdy enough to accommodate the size or weight of regular solar panels, thin film panels could be a solution.

There are four basic kinds of thin film solar panels, with each offering its own benefits and drawbacks. And when compared to their more common polycrystalline and monocrystalline counterparts (with average efficiencies between 13- to 16-percent or 15- to 23-percent, respectively) they don't perform quite as well.

Amorphous silicon (a-Si)

Amorphous silicon panels predate all other thin film panels, and have been in use for decades in small electronics like solar-powered calculators and watches. Additionally, they can still be found in lots of modern devices like solar-powered exterior lights — and those ever-present calculators.

These panels are basically just a thin layer of silicon spread over another surface like plastic, glass, or metal, while their flexibility makes them tougher to physically break. Low light conditions doesn't hamper the performance of a-Si panels very much, either, and they're also the least expensive to produce of the four main thin film panel types. Making these the cheapest (on a cost per-panel basis) option, though not necessarily the best or most overall-affordable one.

On the other hand, the overall efficiency of a-Si panels isn't great at around 6-8%. That low efficiency only gets lower over time, too, with levels often dropping as soon as they're installed in whatever device they're intended for. They don't usually last as long as other panel types, either.

Organic photovoltaic (OPV)

Organic photovoltaic solar panels provide better efficiency (with an 11% average rating) than a-Si panels and won't lose efficiency as quickly. The materials used in their construction are also quite common, so manufacturing is relatively inexpensive when compared to other thin film models.

Something a bit more unique to OPV panels is the variety of colors they can be produced in when different kinds of absorbers are used during production (they can even be transparent). Which can work well for less visually intrusive sun-powered energy setups like solar shingles.

While this does make OPV panels comparably affordable (though maybe not quite as low-cost as a-Si panels), they don't tend to last as long as other non-organic options. Currently you're looking at an approximate lifetime of around 10 years or so. The general cost and aesthetic options can be a good fit for the short-term (or short-ish, anyway), but OPV panels are likely to need replacing far more often than other types of thin film panels.

Cadmium telluride (CdTe)

From the oldest, now to the most prolific. Cadmium telluride solar panels are currently the most commonly used kind of thin film solar panel, and will also pay for themselves the fastest out of the other thin panel types.

CdTe panels are also the less expensive option when it comes to consumer-level thin film panels — yes, a-Si panels are even cheaper but they're not suited for powering a home. They're also more efficient at around 9-15%, making them not quite but almost on-par with polycrystalline panels. On top of that, CdTe panels provide the lowest overall carbon footprint of the thin film lot. So they're comparably affordable, relatively efficient, and are the most environmentally friendly.

The catch is the cadmium, which is very toxic. It's no danger when the panels are being installed or used, but it does pose a potential health risk to the people who manufacture them and that toxicity makes getting rid of CdTe panels (i.e. throwing them away) a problem.

Copper indium gallium selenide (CIGS)

Copper indium gallium selenide panels boast an efficiency of 12-14%, putting them pretty much neck-and-neck with CdTe and very close to polycrystalline panels, energy-wise. They're composed of layers of each element (copper, indium, etc) stacked on top of each other — like a cake — and can be spread over a variety of materials like glass, plastic, and some metals.

CIGS panels do sometimes contain cadmium, in which case they're just as safe to use and risky to dispose of as their CdTe counterparts, however some CIGS panels are built using much safer zinc oxides. Ideally these would be the go-to for thin film solar panels, even over CdTe, but one major factor is holding them back.

Cost is the biggest issue with CGIS as the manufacturing process is significantly more expensive. This means they're less accessible (price-wise) than a lot of other solar options, and it takes much longer for them to pay for themselves in energy savings.