This Cannibal Star Has A Badass Metal Scar

What happens when a star dies depends on its mass. If a very massive star runs out of fuel, it explodes in a huge event called a supernova. But a more modestly sized star, like our sun, will puff up to become a red giant before throwing off its outer layers of gas to form a nebula, a process which leaves behind a small, dense core called a white dwarf.

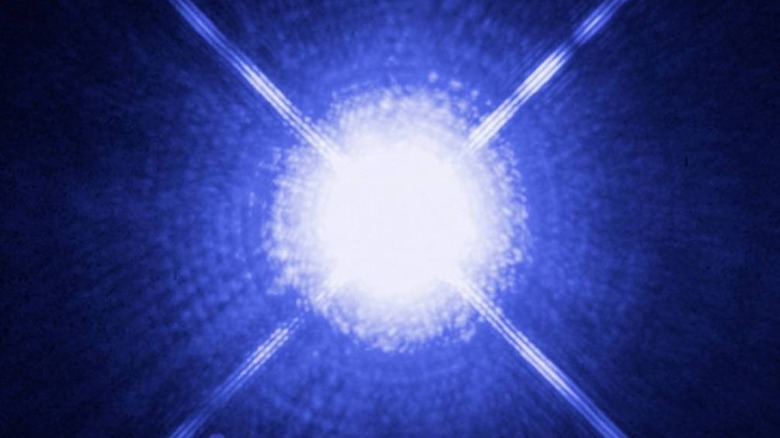

White dwarfs, or dead stars, no longer make their own heat and light. But they still emit heat as they cool over thousands of years, radiating out the last of the energy they created while fusion was occurring within them. And though small, these cores are dense, which means they have a powerful gravitational field around them.

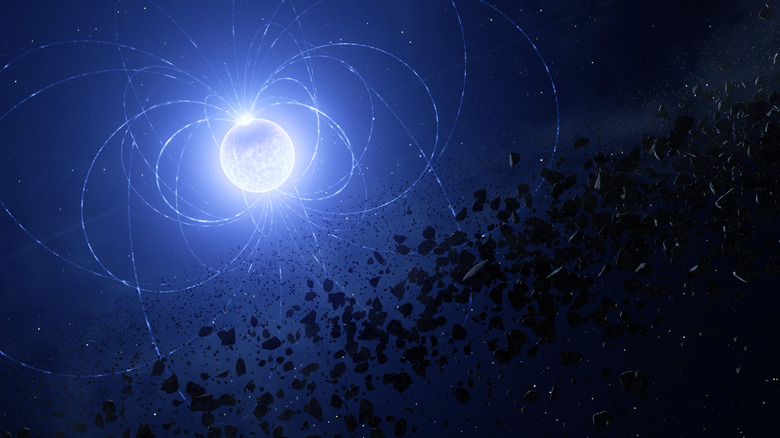

White dwarfs can therefore pull in material from around them, devouring parts of their stellar systems like cannibals. They can even pull apart chunks of planets, giving them the nickname of cannibal stars.

Astronomers using the European Southern Observatory's Very Large Telescope have been researching these white dwarfs for a study published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters, and one, in particular, has taken their interest for having a distinctive metal scar on it.

"It is well known that some white dwarfs — slowly cooling embers of stars like our Sun — are cannibalizing pieces of their planetary systems. Now we have discovered that the star's magnetic field plays a key role in this process, resulting in a scar on the white dwarf's surface," said lead author of the study, Stefano Bagnulo of Armagh Observatory and Planetarium in Northern Ireland.

How to spot a metal scar

The white dwarf that has researchers intrigued is called WD 0816-310, and it is the remnant of a star slightly more massive than our Sun. All that remains of that star now is the white dwarf core, which is about the same size as Earth.

The researchers were able to learn about this metal scar by seeing how metals were distributed across the star's surface. The metals aren't evenly spread but are rather concentrated in particular areas. They could tell this by seeing how the strength of the signal coming from the metals changed in strength as the planet rotated.

The changes in detection levels of the metals were also related to changes in the magnetic field of the white dwarf. The results suggest that the metals are clumped around the magnetic pole, which gives a clue to how they got there: The researchers think that the magnetic field acted like a funnel for incoming matter from the planetary chunk, pulling it onto the star's surface and creating the scar.

"Surprisingly, the material was not evenly mixed over the surface of the star, as predicted by theory. Instead, this scar is a concentrated patch of planetary material, held in place by the same magnetic field that has guided the infalling fragments," said co-author John Landstreet of Western University, Canada. "Nothing like this has been seen before."

How a star gets a metal scar

To look at the star and its scar, the researchers used an instrument on the Very Large Telescope called the FOcal Reducer and low dispersion Spectrograph (FORS2) which can split light into different wavelengths, and see which ones have been absorbed. The absorbed wavelengths correspond to particular elements in the target's composition — in this case, they show the metals that are present on the scar of the star. They were also able to link the location of the scar with the star's magnetic field.

The fact that the composition of metals can be observed, along with the fact that they are located around the magnetic pole, gives information about how the star got its metal scar. This star has a concentration of metal elements across its surface, which seem to have come from a chunk of planet that the star pulled in from its stellar system due to its gravity. The composition of the metals suggests that the chunk that they came from was a big one, at over 300 miles across.

This is the first time that such a clear indication has been found of a white dwarf star cannibalizing matter from its stellar system.

"We have demonstrated that these metals originate from a planetary fragment as large as or possibly larger than Vesta, which is about 500 kilometers across and the second-largest asteroid in the Solar System," said co-author Jay Farihi of University College London.