10 Of The Most Famous Engineers The World Has Known (And What They Accomplished)

Humans are curious by nature, sharing an inherent thirst for knowledge to better both ourselves and humanity as a whole. Yet it takes a brilliant mind to harness that knowledge and use it to invent tangible objects that improve our lives. Engineering combines science and mathematics to overcome common problems, using the resources that nature and technology provide. History's most prominent engineers have revolutionized how we think, how we travel, how we communicate, and how we live more comfortably as a society.

While technology has evolved since the Stone Age, engineering has seen great advancements, first in antiquity, as we saw breakthroughs in mathematics, science, and architecture, then again in the Renaissance, as people started to rethink conventional wisdom and question our place in the universe. Engineering accelerated during the Victorian era, as new manufacturing methods emerged and the spoils of colonialism fueled industry, culminating in the era of space travel and digital technology of today.

Here is our list of the most accomplished engineers in history, from antiquity to the present day, listed chronologically by their date of birth, discussing their significant achievements and impact on later generations.

Archimedes

Some of the greatest political, mathematical, and engineering principles were born in antiquity, and few engineers have left a greater legacy than Archimedes. This renowned mathematician, astronomer, physicist, engineer, and inventor discovered many commonly used principles of mathematics, and created several useful inventions.

Archimedes was born around 290 BCE in Syracuse, Sicily, which was then a colony of Greece. While Greek civilization produced many prominent mathematicians and philosophers, Archimedes was adept at turning his ideas to practical use. After studying at the intellectual hub of Alexandria, Egypt, with prominent mathematician Eratosthenes (who first accurately calculated the circumference of the Earth), he first became known for designing war machines.

These early weapons included catapults, a giant claw that could pluck Roman galleys from the ocean and dash them on rocks, and a system of mirrors that could concentrate the sun's rays on ships, blinding their occupants and setting them on fire. Yet Archimedes' more enduring inventions were more practical and educational in nature.

Later inventions included the Archimedes Screw, a rotational device that could raise water through a tube for irrigation and other purposes. He is also known to have devised a working model that recreated the planets' movements within the solar system. From this, it is widely thought that Archimedes designed the Antikythera Mechanism, the first known analog computer, rediscovered by sponge divers in the early 20th century.

The great Archimedes died during the sacking of Syracuse by the Roman army in 212 BCE. While not much is known of him as a man, his legacy as one of the most important engineers and mathematicians ever to walk the Earth endures to this day.

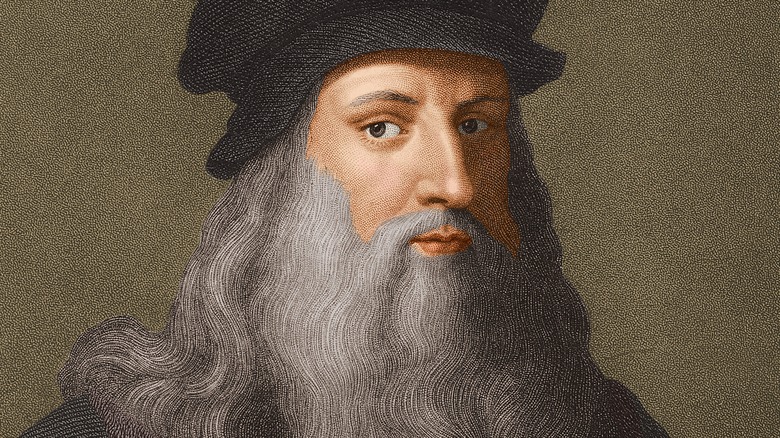

Leonardo Da Vinci

Leonardo Da Vinci epitomized the Renaissance with his impressive abilities as a painter, architect, sculptor, and engineer. Born in northern Italy on April 15, 1452, he is best known for his iconic artworks, such as the Mona Lisa and Last Supper, which rank among the most famous ever created, but this artistic flair was fueled by his interminable interest in the world around us. Art and science were of equal importance to Leonardo, and his powers of observation led to many fascinating ideas in the field of engineering.

Sponsorship from prominent figures of the era, including the Duke of Milan, the Medici family, and Pope Leo X, allowed Da Vinci to pursue his love of engineering, and he invented a variety of machines and discovered many uses for levers and geared engines throughout his lifetime. These machines were often unique in their day and spanned many different subjects. They included an anemometer for measuring wind speed, an aerial screw that was a precursor to the modern helicopter, multi-barreled guns, a more accurate clock mechanism, underwater swimming gear, and a parachute. Two of his most famous inventions were his concepts for a primitive flying machine and a self-propelled cart, predating the airplane and automobile by around 400 years.

Sadly, Leonardo's inventions were rarely realized during his lifetime, with much of his vast body of work being lost over the centuries. Many of his ideas were simply ahead of their time, and it wouldn't be until the invention of modern materials and the internal combustion engine that they could be put to practical use. However, these ideas inspired countless engineers that followed, and his contributions served as an important evolutionary step toward modern engineering practices.

Isambard Kingdom Brunel

The Victorian era was a highly productive period that witnessed many great feats of engineering, and nobody personified this era better than Isambard Kingdom Brunel. Renowned for taking great financial and technological risks to achieve his objectives, Brunel was given to question conventional wisdom and, in doing so, completed some of the world's most impressive engineering projects.

Born in Portsmouth in the south of England, Brunel was schooled in mathematics in France at the Lycee de Paris. Upon returning to England, he was assigned to oversee the construction of London's Thames Tunnel, which collapsed and nearly killed the young engineer. At 24 years old, while recuperating in the west of England, he submitted his design for the Clifton Suspension Bridge, spanning a large gorge in the city of Bristol. The 1,352-foot-wide bridge is still a popular vehicle thoroughfare today, more than 150 years later. Brunel went on to build the Great Western Railway, linking London with the west of England, which included the Box Tunnel, the longest of its day at over two miles in length.

In the early 1800s, no steamship could carry enough coal to facilitate a transatlantic crossing. Brunel calculated that a ship's weight did not affect its resistance through water and designed the largest ship the world had ever seen, the SS Great Britain. Not content with creating the first transatlantic vessel, he set about building the SS Great Eastern, which was twice the previous ship's length at almost 700 feet.

Sadly, Brunel died a month after the SS Great Eastern's launch, suffering a fatal heart attack at 53 years of age. He remains one of the most prolific engineers ever to have lived, with a lasting legacy of bridges, tunnels, railways, and steamships, many of which are still in operation today.

Ada Lovelace

Computer science is a subject that became current to the general public in the mid-20th century. However, its seeds were planted around 100 years earlier in the achievements of Ada Lovelace. Like many great engineers, Lovelace defied convention, eschewing traditional Victorian values and working hard to receive a full education — a privilege denied to many women at the time.

Ada Lovelace never met her father, the notorious poet Lord Byron; nevertheless, her mother encouraged mathematics in an effort to steer her away from her father's temperamental attitude and artistic pursuits. This served the young noblewoman well, as she found she had an aptitude for analytics and struck up a friendship with Charles Babbage, a noted mathematician and inventor who was working on a primitive calculator called the Difference Engine. This idea was shelved when funding was pulled, and Babbage started work on the more complex Analytical Engine, which also floundered as the inventor began to lose interest.

Ada Lovelace saw great potential in the Analytical Engine and forged ahead. Realizing that the machine could manipulate symbols as it could numbers, she applied symbolic logic to enable the device to complete more complex tasks. Eventually, Ada successfully managed to produce accurate calculations using the algorithms she designed on a series of punched cards. Working closely with the Analytical Engine's designer, Charles Babbage, she is credited with programming the world's first computer. It was a huge development in the annals of computing, laying the foundations for the future of computer science and the world at large in the centuries that followed. She is celebrated in October each year on Ada Lovelace Day, which recognizes the contributions of women in STEM disciplines.

Nikola Tesla

The name Tesla has reentered the common lexicon thanks to the popular car maker. Yet, as impressive as these vehicles may be, their original namesake was arguably the most important player in the early days of electrical engineering. We use the word "arguably" because the Nikola Tesla story involves not one but two great engineers: Tesla and Thomas Edison.

Tesla was born in Serbia in 1856 and became an early mathematics and electrical engineering prodigy. Arriving in the United States almost penniless, he was employed by Edison to find an alternative to his direct (DC) current, with the offer of $50,000 if he was successful. Tesla soon responded with his model for alternating (AC) current, which was easier to generate, transmitted better over long distances, and was cheaper to maintain. Somewhat typically for his character, Edison reneged on the deal, and the "War of the Currents" commenced. Ultimately, Tesla won after Westinghouse bid to use it in competition with Edison's General Electric company.

Nikola Tesla went on to invent the "Tesla Coil," a powerful electrical coil that made neon and fluorescent lighting possible, and could be used in X-rays and wireless transmissions. The latter became Tesla's next big passion project, but he lost out in the race to Italian inventor Marconi, who was instead credited with the radio's invention, leading to Tesla having a mental breakdown.

This disappointment appeared to be the final straw for Tesla, who withdrew from public life, became fixated on pigeons, and showed many obsessive-compulsive characteristics. He ended his life living a solitary existence in a New York hotel but has since become widely celebrated as a founding father of modern electronics.

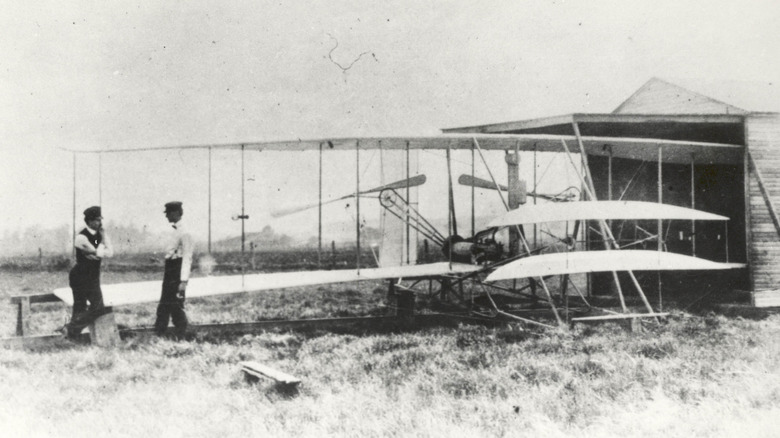

The Wright Brothers

From their humble beginnings in Dayton, Ohio, Orville and Wilbur Wright became two of the most celebrated engineers in history as the fathers of controlled flight. Their inventions not only revolutionized the way we communicate and the way we travel, but also changed the way we view the world that we inhabit.

With money gleaned from their successful bicycle manufacturing business, the Wright brothers could fund and build their ideas for a powered flying machine as a craze swept the nation with ideas for different flying contraptions. Orville and Wilbur noticed that these machines lacked directional control and set about designing a machine that could fly in three dimensions, with control for pitch, roll, and yaw.

In 1903, after a prolonged experimental period in a field in Kitty Hawk, NC, the "Wright Flyer" aircraft, equipped with a lightweight engine built by mechanic Charlie Taylor in the Wrights' workshop, made a series of successful, controlled flights. The Wrights had achieved the ultimate feat of avionic engineering, and the world was changed forever.

Orville and Wilbur Wright perfected their aircraft in Huffman Prairie, OH, and were celebrated as heroes for their efforts. Before long, airplanes were in widespread use worldwide. Sadly, Wilbur died in 1912, but Orville lived to see oceans crossed and battles being fought in the skies, and just 21 years after his passing in 1948, humans first set foot on the Moon.

Guglielmo Marconi

Guglielmo Marconi was born in Bologna, Italy, in 1874 and was among the first to realize that human communication was possible via radio waves. He designed and built the apparatus that would prove his theories, and traveled to England at age 22 to patent and test his ideas.

Marconi's experiments progressed quickly, from sending a signal across the UK's Bristol Channel, which is a relatively small body of water, to across the English Channel to France, which is a distance of many miles, to across the Atlantic Ocean to Newfoundland at a distance of over 2,000 miles. He achieved all this in a matter of just five years, and in doing so, he disproved the commonly held theory that radio signals would be disrupted by the curvature of the earth.

Marconi invented aerials for transmission and a magnetic receiver, which became industry standards worldwide and were used for communication in the shipping industry. Notably, the distress call of the Titanic was sent on an early Marconi unit in 1912. By this time, Marconi had already been awarded the Nobel Prize for physics. He went on to work on improving long-range transmissions and worked with television signals later in life, further cementing his reputation as a master of electrical communications.

Henry Ford

Henry Ford, one of the world's most celebrated industrialists, was born in 1863, as the United States was in the throes of the Civil War. A Detroit native, he completed an apprenticeship as a machinist before becoming chief engineer of the Edison Illuminating Company in Detroit. He and Thomas Edison established a lifelong friendship before Ford turned his attention to automotive engineering in 1893.

Work on Ford's first car, the Quadricycle, was completed in 1896. He built and raced a series of cars and established the Henry Ford Company, which would later become Cadillac after his departure. His next venture, the Ford Motor Company, would be the business that made his name. The new company developed assembly lines that were highly efficient, revolutionizing mass production and making the automobile a household item.

Ford's Model T car was a breakthrough in simplicity, reliability, and affordability, and perfectly represented his vision of a car for everybody. It was easy to operate and, thanks to the company's trailblazing production model, cheap to buy, as Ford passed his savings back to the customers. This became the blueprint for subsequent Ford automobiles and the industry as a whole. Before he passed away in 1947 at the age of 83, Henry Ford had helped motorize the world, and his name still adorns one of the most successful companies in automotive history.

Alice H. Parker

There have been many advancements in engineering over the last 200 years, but few have made as great an impact on quality of life as central heating. Up until the mid-20th century, wood- or coal-burning fireplaces were the primary source of heat for the average household. Not only was this fuel prohibitively expensive for many, but these heaters were largely impractical, especially within highly developed areas; they caused pollution and its associated health risks, and posed a significant fire hazard.

Alice H. Parker patented a design for the precursor to modern central heating. While little is known of this trailblazing early 20th-century African-American woman, her influence has spread far and wide. We do know that she was born in Morristown, New Jersey, in 1895 and received a college degree from Howard University in Washington, D.C. (pictured), which was a refreshingly inclusive institution for the time.

Parker's patent for a natural gas central heating furnace was filed on July 9th, 1918, and was notable for its system of individually controlled furnaces. This idea for heat regulation was carried over to later designs, and was influential in thermostat technology and the idea behind isolated heating zones within a building. Sadly, no verified images remain of Alice H. Parker, and little is known of her activities in later life. However, she remains an important figure in engineering, especially in her home state of New Jersey, where the Chamber of Commerce bestows the Alice H. Parker Women Leaders in Innovation Award every year.

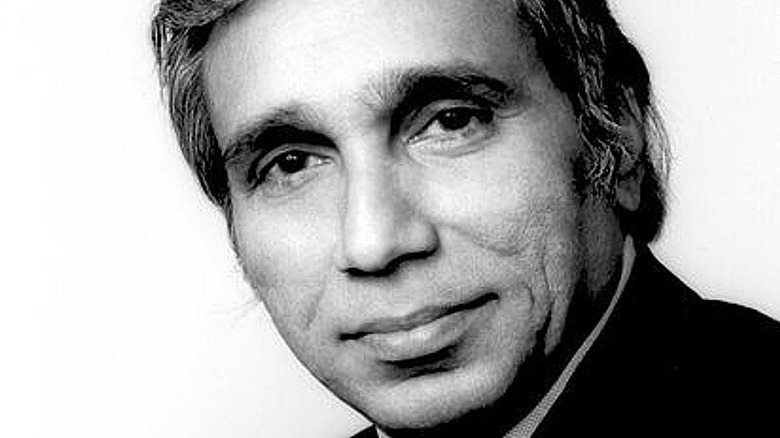

Fazlur Rahman Khan

The Bangladeshi-American structural engineer Fazlur Rahman Khan is credited as the father of the modern skyscraper. He was born in Dacca, Bangladesh, in 1929, where he received a bachelor's degree in engineering. He then traveled to the United States to attend college in Illinois, where he received two master's degrees in structural engineering and theoretical and applied mechanics and a Ph.D. in structural engineering. Young Dr. Khan was certainly a prodigy, as would be proven time and again over the course of his impressive career.

Khan developed modern tubular techniques for constructing high-rise and large-scale buildings. As a partner in the architectural firm Skidmore, Owings, and Merrill, he was instrumental in developing the groundbreaking "bundled tube" system that made it possible to build taller buildings than ever before while maintaining their structural integrity. The concept proved cost-effective as well, ushering in a new era for tall buildings and revolutionizing modern architecture, especially since firms could now capitalize on real estate by building higher.

Among Fazlur Rahman Khan's creations is the Sears Tower (now the Willis Tower) in Chicago, which was the first to use his tubular system (and was, at the time, the tallest building in the world), Chicago's John Hancock Center, and One Shell Plaza in Houston. Dr. Khan worked incredibly hard throughout his life, publishing over 75 papers and lecturing at Chicago's Institute of Technology in his free time. By the time he died an untimely death at just 52, he had made a great impact on architecture, with a legacy that continues in the progressively taller and more impressive structures that appear all over the world.