The Mysterious Antikythera Mechanism: Was This The World's First Computer?

Antikythera is a diamond-shaped island in the Mediterranean Sea, situated between Greece's mainland and the island of Crete. It's small, covering just 8 square miles, and the population holds stable at under 100 permanent residents, well below the number of wild goats that call the island home. Antikythera is mostly bound by sheer limestone cliffs, interrupted only occasionally by narrow pebbly beaches. In the north are the ruins of an ancient castle, and in the south one can visit an old stone lighthouse. It was here, in this unlikely setting and quite by accident, that the world's oldest computer was discovered.

The Antikythera mechanism, as it has come to be known, is an artifact that seems out of sync with the historical timeline as we're familiar with it. As the first computer that we know of, it predates not only the microprocessor, but also the motherboard, the transistor, vacuum tubes, and punch cards. It was built at a time before the coining of the words software, hardware, and even electricity. The Antikythera mechanism is over 2,000 years old.

Who built this device, and why, and how do we know? What's its purpose, and how does it function? And is it really even a computer at all? For the answers to these questions we'll first have to step back in time, not to the time of the Roman Empire, but instead to the time of the Second Industrial Revolution to visit a crew of Symian divers.

The Antikythera wreck

Symi is another Greek island, not especially large itself, just off the southwest coast of Türkiye. In 1900, a crew of sailors embarked from Symi toward the coast of North Africa. They were divers who collected natural sponges from the seafloor for a variety of commercial uses. When the weather became unfavorable, they stopped to shelter off the coast of Antikythera. Before departing again, they decided to dive for sponges. The first diver descended into the salty depths only to quickly return, claiming to have seen a mound of dead people. Believing the diver had hallucinated, the captain himself went down next. When he resurfaced, he carried with him a human arm. It was made of bronze. The dead people had in fact been statues.

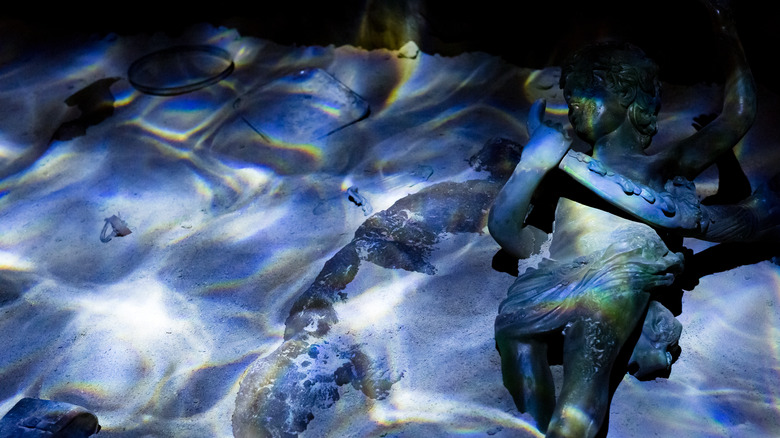

Completely by chance, these divers had discovered the wreck of an ancient Roman merchant ship carrying Greek artifacts. What followed is widely credited as the first-ever underwater archeological dig, leading to methods and developments still used in modern times. Over the next two years, divers recovered numerous relics from the wreck including jewelry, coins, and sculptures of bronze and marble.

Among the recovered artifacts was an unassuming brick that was sent to the National Archaeological Museum in Athens where it sat for several months, overshadowed by the many more obvious treasures. But then the brick cracked open, revealing a set of tiny precision gears. Thus began the unraveling of the mystery of the Antikythera mechanism.

A puzzle missing most of its pieces

What was the purpose of these tiny gears? It was this question that fascinated and eluded scientists and laypeople alike for more than a century. A substantial barrier in the quest for an answer is the fact that two-thirds of the original device remains at large. It's possible that other pieces might still lay on the bottom of the Mediterranean, but subsequent dives in more recent years haven't turned up any clues. Of the third that has been recovered, it's now fractured into 82 pieces.

Still, the pieces of the Antikythera mechanism that we do have provide valuable insights into both the mechanical talents and the knowledge of the physical world its creators possessed. Though now corroded, the 30 bronze gears demonstrate manufacturing precision on the millimeter level. Fine engineering on this order was not thought to have been possible on the European continent for at least another 1,000 years.

To learn more about the how and the why of the Antikythera mechanism, researchers scanned the device in 3D high-resolution using X-ray computed tomography. These images allowed scientists to see inside the strange artifact in a way previously not possible, revealing additional engineering complexity and sophistication, as well as tiny inscriptions in ancient Greek. At last, the Antikythera mechanism began to give up its secrets.

A celestial calculator

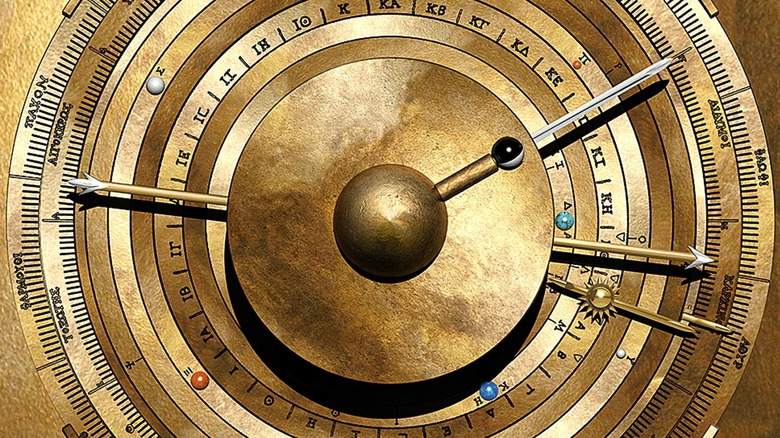

The inscriptions and internal workings, once revealed, confirmed what many scientists had long suspected but were previously unable to prove: the Antikythera mechanism was an ingenious device for predicting celestial events. Over the next decades, additional research led to a detailed working model that included the likely functions of the mechanism's still-missing pieces. Amazingly, the device incorporated the knowledge of ancient Greece, Babylon, and Egypt together in a single machine.

There are dials and hands on both the front and back faces of the device. The dials displayed accurate information about the date, along with the relative motions of the Earth, moon, and sun, and positions within the Zodiac. They showed the phases of the moon, accounting for irregularities caused by its elliptical orbit. They charted the motions of the five planets that were known at the time: Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn. They provided information about the passing of seasons, the rising and setting of major constellations and specific stars, and the periodic cycles of the original Olympiads. They even predicted solar eclipses.

The entire device operated as a mechanical computer with a hand crank that allowed the user to advance or rewind the date at will to get information about past or future celestial events. Nothing approaching this level of sophistication from this time period has ever been discovered. This, along with its advanced ability to mechanically make predictions, has earned the Antikythera mechanism the title of the world's first computer.