The 10 Most Influential Women In Automotive History

The history of the automotive industry is filled with innovators and visionaries. Many of the most famous brands are named after the men who founded their respective automotive companies — Ford, Oldsmobile, Mercedez-Benz, Toyota, Honda, and many more.

However, beneath this male-dominated narrative lies the overlooked or ignored contributions of women. Many of these cars simply wouldn't be the same if it weren't for the trailblazing women behind the scenes. At the time, history largely ignored or airbrushed the impact women had on the automotive industry. However, as these events slip further into the past, we can look at them with a new perspective.

In this article, we're showcasing 10 influential women who changed the automotive industry forever. Although there are undoubtedly many more women who should be recognized for their efforts, these 10 were pioneers in their field and not only faced the unknown when it came to automobiles but also faced adversity through the societal pressures that they endured. These women, whether they were designers, drivers, or engineers, helped to fundamentally change the automotive landscape into what we know today — all while shattering barriers and paving the way for future generations.

Margaret Wilcox (1838-1912)

Born in 1838, Margaret Wilcox was a trailblazer. Not only did she earn a degree in mechanical engineering in the 19th century, but she did so at a time when few women ventured into STEM fields — areas which, even today, remain predominantly male-dominated.

A natural innovator, Wilcox approached challenges with inventive solutions. Her most significant contribution to the automotive world was the development of an early car heating system. This system channeled air over the engine's heated block, redirecting it into the vehicle's interior. This innovation marked the inception of vehicular climate control, ensuring drivers remained warm and could defrost their windows for better visibility. However, her design had limitations — it lacked a mechanism to regulate the heat, causing the interior to become progressively hotter on extended drives.

Nevertheless, her pioneering work laid the foundation for subsequent advancements in automotive climate control. Recognizing its potential, the Ford Motor Company integrated a refined version of this system into their Model A in 1929.

Navigating the world of invention as a woman in the 1800s was no small feat. Margaret Wilcox faced societal biases and gender-based challenges. It's even reported that she had to file patents under her husband's name due to prevailing prejudices, although other reports claim that she received full credit. Her achievements, against such odds, underscore her remarkable resilience and ingenuity.

Bertha Benz (1849-1944)

Bertha Benz was a shrewd inventor and businesswoman. From a young age, she displayed a keen interest in machinery and a knack for repairing them. Her path eventually crossed with Carl Benz, whom she would not only financially support in his endeavors but also buy out his business partner's stake before they were married.

Before they wed, Carl had made multiple unsuccessful attempts to design one of the first cars ever invented, the horseless carriage. With Bertha's help, they successfully developed a two-stroke engine. Although the automobile worked, there was a lot of skepticism about its practicality and function, which meant Carl was unable to drum up support for the invention.

Instead of arguing with naysayers, Bertha set out to prove them wrong by taking the first long-distance car ride in 1888 with her kids to visit her mother. Bertha and her family went on a 60-mile journey from Mannheim to Pforzheim, Germany. It took approximately 13 hours and she had to repair several components along the way — in fact, she even created rudimentary brake pads with the help of a smith in Bruschal to solve a braking issue.

Bertha Benz is a testament to the adventurous spirit that many in the auto industry still feel and are inspired by today. The route she took still bears her name and can be driven to this day.

Mary Anderson (1866-1953)

Mary Anderson is credited with inventing a car feature that many take for granted — the windshield wiper. The story goes that the inspiration for Anderson's invention came during a trolley ride in New York. Amidst a storm, she observed the driver frequently leaning out to clear the snow from the windows or halting the trolley entirely.

Such practices posed significant safety risks. Driving with your head out of the window is unsafe, decreased road visibility is unsafe, and stopping along the side of the road is unsafe in the best of weather conditions. To address this, Anderson designed a device operated by an interior lever. This lever, equipped with a counterweight and spring, ensured the wiper blade maintained contact with the window and moved smoothly across it.

While Anderson wasn't the first to create a window-cleaning mechanism, her design was the first that actually worked — although another woman would help automate the device and bring it to mass production.

Charlotte Bridgwood (1861-1929)

Charlotte Bridgwood, initially a Vaudeville actress, later became the president of the Bridgwood Manufacturing Company, where she pioneered several automotive safety innovations. She is best recognized for improving Mary Anderson's windshield wiper design. Bridgwood's significant contribution was the mechanization of the wiper, eliminating the need for drivers to manually operate it using a lever. She also introduced rollers in place of blades on the wiper arm, though this design did not gain widespread acceptance, and blade-style wipers remain the standard.

Regrettably, Bridgwood's mechanized windshield wipers did not gain traction during her lifetime. Investors dismissed the invention as superfluous, and she struggled to secure funding or potential buyers. As a result, her design remained largely a prototype, with its patent documentation gathering dust. However, in 1920, after her patent largely unused had expired, Cadillac recognized the wipers' potential and made them a standard feature in all of their vehicles.

Florence Lawrence (1886-1938)

Florence Lawrence was a pioneering figure in the early 1900s, renowned for her significant contributions to both the film industry and the automotive world. Often hailed as the first movie star, her cinematic legacy has sadly faded with time. However, over the course of a career where she appeared in over 250 silent films under her belt with the Biograph studio, Lawrence not only showcased her acting talents but also her daring spirit — even staging a car crash for promotional purposes.

Beyond the silver screen, Lawrence played an instrumental role in her mother's manufacturing business. As a passionate driver, she was perturbed by the lack of communication on the roads, leading her to invent the first turn and brake signals. Her turn signals were innovative placards indicating direction, while her brake lights prominently displayed the word "stop."

Today, while many drivers may take these signals for granted, their absence can lead to road rage and accidents. Regrettably, Lawrence chose not to patent her groundbreaking inventions, believing they should benefit society at large. This altruistic decision allowed major automobile companies to patent and profit from her designs, leaving her without any financial recognition whatsoever. While Florence Lawrence's name may not resonate in the realm of cinema as it once did, her invaluable invention continues to safeguard drivers globally.

Emily Post (1872-1960)

Emily Post was a pioneering figure in American automotive culture. Renowned for her seminal work, "Etiquette in Society, in Business, in Politics, and at Home," her most notable contribution to the world of automobiles was her book, "By Motor to the Golden Gate." In this work, she detailed her cross-country journey with her son from New York to California. While she wasn't the first or the fastest to traverse this route, Post's objective was distinct. She aimed to experience the journey with utmost comfort, treating it as a leisurely holiday. She documented tourist attractions, scenic spots for relaxation, and captivating sights throughout her travels.

Post's approach was revolutionary for her era. At a time when female drivers were a novelty, she reshaped societal perceptions. Rather than emphasizing the adventurous spirit often associated with driving, she highlighted the luxury and everyday nature of the activity, making it relatable to women of her generation. Using her authority in etiquette, she played a pivotal role in normalizing the idea of women having autonomy in driving, a concept that was not commonplace before World War I.

Furthermore, Post was instrumental in establishing a social code for women drivers. In her 1922 edition of "Etiquette," she asserted that women did not require a chaperone while driving. She firmly believed that it was entirely appropriate for a woman to drive alone or even with a male passenger.

Dorothée Pullinger (1894-1986)

During World War I, a significant number of factory and domestic roles remained vacant due to the mobilization of eligible men to the frontlines. This situation paved the way for the emergence of a robust women's workforce, acting as a driving force for the advancement of women's rights and autonomy. A prominent figure in this movement was Dorothée Pullinger. She took the helm of an automobile factory in Scotland, serving as its superintendent and managing 7,000 employees in car production.

Pullinger later rose through the ranks to the role of director at Galloway Motors. In this capacity, she oversaw the production of the only automobile model explicitly designed for women. This initiative was groundbreaking, especially in an era when societal norms largely excluded women from privileges, deeming automobiles as a domain reserved for men. The war had temporarily disrupted these norms, but post-war, there was a strong inclination among many men to revert to traditional gender roles, confining women to domestic responsibilities.

However, trailblazers like Dorothée Pullinger resisted this regression. Through her innovations and leadership, she not only retained the progress women had made during the war but also underscored the message that women have an equal place to men in every sphere of society.

Clärenore Stinnes (1901-1990)

Clärenore Stinnes emobdies the human spirit of adventure. She was the first person to circumnavigate the world by automobile — no small feat, especially in 1927.

Born in Germany, Stinnes developed a passion for cars early on, honing her skills by driving around her father's factory premises. By the age of 24, she had returned to Germany and began participating in racing tournaments, quickly rising in popularity and gaining a reputation as a shrewd driver as her wins piled up. In 1927, Clärenore Stinnes wanted to do something that nobody else had achieved. Accompanying her was Swedish photographer Carl-Axel Söderström, tasked with capturing the journey.

Her route was nothing short of challenging. She navigated the treacherous terrains of the Gobi Desert and Siberia, voyaged to Japan and Hawaii, traversed both North and South America, crossed the Atlantic, journeyed through France, and finally returned to Germany. Their vehicle, the Adler Standard 6, faced multiple breakdowns and needed a transmission replacement shipped from Germany. The journey was fraught with obstacles and physical challenges as many regions lacked proper roads, leading to instances where they cleared paths using dynamite and battled various illnesses during their expedition.

Helene Rother (1908-1999)

Helene Rother stands out as the pioneering female designer in the automotive sector. Born in Germany, Rother fled to Paris with her daughter to escape the clutches of Nazi Germany. However, the subsequent German invasion of France compelled her to relocate again. She eventually found refuge in the United States, where she crossed paths with Harley Earl, General Motors' chief of design.

Prior to Rother's influence, car interiors often featured shades manufacturers believed would effectively conceal dirt. This dull design was the industry norm until Helene Rother was brought on to breathe new life into automotive interiors. She changed the entire industry by creating vibrant interiors that were aesthetically pleasing and practical. She was given free rein over the interiors, including fabrics and hardware like door handles.

Her innovative departure from the conventional beige palette distinguished GM from its competitors, leading to a surge in demand for her designs. In a post-war era where austerity dominated public sentiment, Rother's designs symbolized a shift towards a brighter, more forward-looking aesthetic. Her legacy underscores the notion that design transcends mere functionality, that the public wanted more, and that women can succeed in any traditionally male roles. She was inducted into the Automotive Hall of Fame in 2020.

Suzanne Vanderbilt (1933-1988)

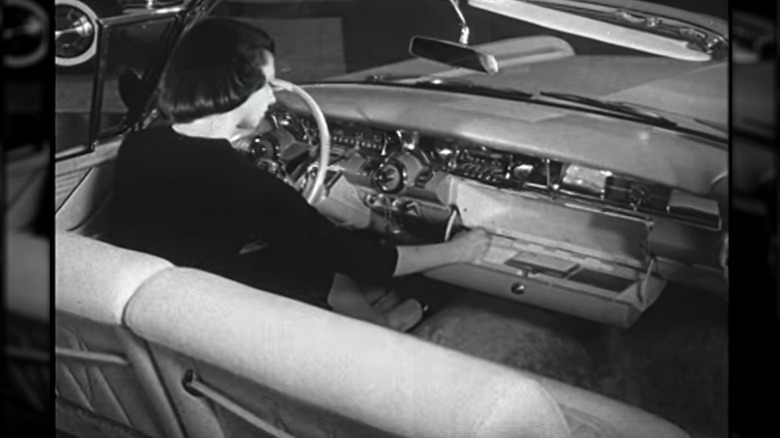

In the 1950s, recognizing the need for a fresh perspective, General Motors established an all-female design team prominently branded as the Damsels of Design. Among these trailblazing designers was Suzanne Vanderbilt. The contributions of these women were transformative, introducing innovations that have since become automotive staples. Features such as retractable seatbelts, backseat storage compartments, and childproof doors owe their inception to these visionary designers.

However, the era's prevailing gender biases posed challenges. These women navigated a workplace rife with sexism, often being labeled as lady or women designers rather than simply designers. Their design purview was limited to interiors, with areas like the dashboard deemed exclusively male territory.

While many members of the Damsels of Design departed GM within a few years, Vanderbilt's tenure spanned 23 years. She played a pivotal role in shaping the automotive industry and championing the capabilities of women designers. Her work at GM underscored the fact that design transcends gender, focusing on functionality merged with aesthetic elegance.