The History Of LimeWire: How It Worked And What Happened To It

Rapidly expanding internet capabilities in the early 2000s paved the way for rogue applications to emerge and fundamentally change the relationship between consumers and media companies. LimeWire is perhaps one of the most well-known P2P (peer-to-peer) file-sharing platforms of all time to offer unrestricted access to music, movies, games, and more. Despite its popularity, LimeWire endured harsh lows to go with its high points and ultimately ceased to exist altogether.

During its peak in the mid-2000s, LimeWire boasted millions of active users. Audiophiles found themselves exposed to an unprecedented library of songs, artists, and genres. While iTunes also came to prominence around this time, LimeWire, apart from being free, also included music and audio files not accessible through Apple's music store. While established artists were forced to cope with their music being downloaded without their consent, up-and-coming artists took advantage of the platform as a way to reach a global audience without record label support.

However, LimeWire's meteoric rise came at a cost. Copyright holders including major record labels and film studios vehemently opposed the platform, arguing that it facilitated piracy and inflicted severe financial losses on the entertainment industry. This notion, and years of litigation, ultimately brought the platform to its knees — but not before it left a lasting impact on the file-sharing world that is still felt to this day.

Here is the history of LimeWire, how the program worked, and what happened to it.

[Featured image by Shazz via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | CC BY-SA 3.0]

About the creator

Mark Gorton, born in 1966, is the founder and creator of LimeWire. He grew up in New Jersey and holds a Bachelor's in Electrical Engineering from Yale University and a Master's in Electrical Engineering from Stanford University. After starting his professional journey as an electrical engineer at Martin Marietta (now Lockheed Martin), he ventured into the realm of fixed-income trading at Credit Suisse First Boston due to his burgeoning interest in business (he received his MBA from Harvard University). Subsequently, he set out on his own path, establishing the Lime group of companies.

Gorton cut his teeth as an entrepreneur and software developer but continues to run Tower Research Capital, the financial services firm he founded in 1998. He is also a staunch advocate of green initiatives, which may just be a coincidence given the prominence of the color green in LimeWire's logo. Gorton has also been recognized as one of the "50 Visionaries Who are Changing Your World" by Utne Reader and recently made headlines for setting up a super PAC for United States Presidential Candidate Robert F. Kennedy Jr.

Little else is known about Gorton's personal life, though it is important to understand his role in launching the application as the man who brought the program to relevancy. While he holds two electrical engineering degrees, Gorton's public persona is that of a businessman above all else. For Gorton, LimeWire's creation was rooted in business more than anything else.

Conception

During the late '90s and early 2000s, digital file-sharing quickly drew a cult following, but existing platforms like Gnutella presented too many challenges for the average user to navigate. Others, namely Napster, only lasted for a couple of years before being shut down for good.

Gorton identified this gap in the market and aimed to develop a more accessible P2P file-sharing application that extended beyond digital audio. He wanted users to be able to share music, videos, images, and software with the click of a button. As a result, he put together a team of engineers in the spring of 2000 to develop software capable of supporting this idea. While the service was not an overnight success, it eventually amassed 1.7 million users — the same as iTunes had at that time — by 2005.

The name LimeWire partially came from Lime Objects, a failed subsidiary that eventually merged into LimeWire. However, the application did not formally take on its new name until shortly before the beta went public in November 2000. As LimeWire COO Greg Bildson wrote in a column on Medium, the development team liked the name LimeNode quite a bit but chose to go with a different name as the words "lime" and "node" are derivatives of plants. With the name LimeWire, the company could pay homage to the application's roots with "lime" while "wire" loosely referred to the program's function — to connect people to all forms of media as efficiently as possible.

Napster influence

While file-sharing systems like Gnutella helped lay the foundation for LimeWire to build on, none were as impactful as Napster. The P2P platform launched in 1999 and allowed audiophiles to share and download MP3 files from each other's computers, offering an alternative to consumers needing to buy CDs, vinyl, and cassettes. With Napster, listeners could download their favorite artist's entire catalog to their hard drives, and the platform soon saw exponential and unprecedented growth. The software launched on June 1, 1999, attracted millions of users, and eventually ceased operations after just two years.

The implementation of such software changed the music industry forever in both positive and negative ways. It revolutionized the way people accessed and consumed music, empowering users with unprecedented access to a vast library of songs. Without Napster, music streaming likely would not exist — but Napster's rapid ascent also threatened to upend the music industry altogether.

As users freely shared copyrighted music on the platform without permission from artists or record labels, it sparked widespread controversy and legal battles with the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA) as well as Metallica suing Napster. The RIAA delivered a deadly financial blow to Napster, and without a legal leg to stand on, the company ultimately shut down for good in 2001. However, this paved the way for LimeWire to enter the stage.

Slow growth

For all of its similarities to Napster, the peaks and valleys of LimeWire did not mirror its audio-only counterpart. Whereas Napster lasted just two years, LimeWire hung around for almost a full decade before being forced to cease operations and did not hit its peak until after the fifth year. This is partially because of how long it took to download files. LimeWire initially used the Gnutella network protocol, which had some inherent inefficiencies that drastically limited download speed. While the LimeWire development team refined and upgraded the network protocol to be more efficient, it took time to move its initial user base over from older versions of the client.

"To say we had a slow start was an understatement," Bildson wrote on Medium. "At the time, we celebrated every 100 downloads and then every thousand but that was just a drop in the bucket ... If anything, we were too conservative in our early days but it gave us time to better understand the space and our competitors. It would take four years at least for this to really pay off."

Coming off Napster's legal issues, the demand for a service like LimeWire vastly outweighed the supply of those sharing files. However, as the client improved and the sheer effectiveness of LimeWire spread by word of mouth, the program eventually accrued four million active users by 2006 as well as 200 million downloads of its client.

How did LimeWire work?

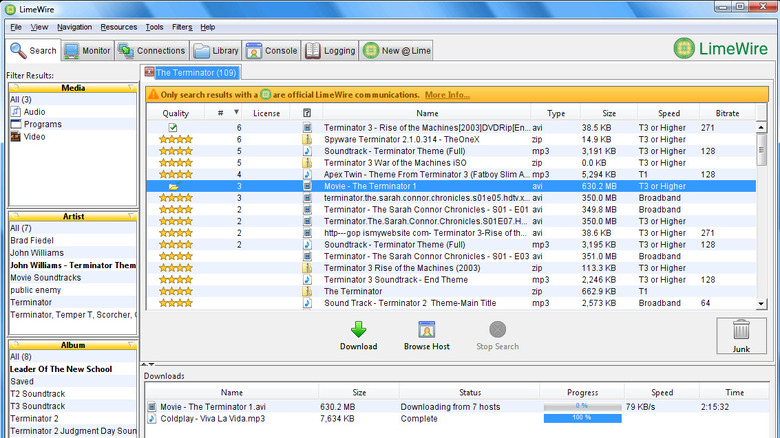

As a P2P file-sharing program, LimeWire allowed its users to download all things digital, and its versatility of files, as well as its ease of use, set it apart from its contemporaries.

Users would first download and install the client in a matter of minutes before connecting to the network and gaining access to a bottomless pit of digital media. From there, users could simply search for content and receive a list of results based on the criteria. The program then established a direct line between the user's computer and the host computer sharing the file, while users could become a source for others by sharing the newly downloaded file themselves. The more sources, the faster files would download.

Since Gorton saw LimeWire as a business, it's a fair question to ask how the company made money. While the client was free to download, LimeWire also offered a paid version called LimeWire Pro, which promised faster download speeds alongside access to free tech support and software updates for six months. The company also made money through bundling agreements, with the free-to-use version coming bundled with additional software from other companies that paid LimeWire to market their product. The New York Times reported that LimeWire reached $20 million in revenue by 2006 — 14 million of which had been made since 2004.

[Featured image by Navy Blue via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | GNU General Public License]

Becoming synonymous with viruses

The tale of LimeWire is that of a double-edged sword in more ways than one. What made LimeWire great — ease of access, inclusivity, and diversity of files — also opened it up to malicious attacks from criminals and derelicts looking to exploit the platform's massive user base for personal gain. Since the program's file-sharing model allowed people to download files from each other's computers, there was no way effective to prevent select files from coming packed with viruses, nor was there a way for users to know they are downloading a virus aside from a vague star-rating system associated with files.

Sometimes, these viruses could come in the form of infected files that once downloaded, can spread malware like wildfire. Other times, files, particularly executables, would have misleading titles, resulting in double the disappointment for those looking to enjoy free content.

One of the most notorious threats associated with LimeWire was the LimeWire Pirate Edition (LPE), which meant even the LimeWire client itself could pose as a virus if downloaded from a non-official source. Towards the end of Limewire's lifecycle, it was estimated that one out of every three files on the service contained a virus or some form of malware or spyware. Johnny Tan, a systems administrator at LimeWire, told Mel Magazine that LimeWire was "laissez-faire" with viruses, believing its rating system and a newly proposed method for users to purchase music to be an answer to the client's virus problems.

Initial RIAA pressure and lawsuit

LimeWire's spike in growth ended up being detrimental to the company's future as it attracted the attention of the RIAA in 2006. Kazaa, another P2P filesharing platform, had settled with the RIAA, the MPAA (Motion Picture Association of America), and the International Federation of Phonographic Industries (IFPI) just a week before LimeWire received its first significant legal threat.

The LimeWire suit alleged the company facilitated the illegal sharing of music and failed to make any material effort to stop the piracy on its network. In addition, the RIAA alleged LimeWire not only had knowledge of but encouraged illegal filesharing to boost the platform's visibility. "While other services have come productively to the table, LimeWire has sat back and continued to reap profits on the backs of the music community," the RIAA said at the time, as reported by Ars Technica. The company initially sought damages plus a $150,000 fine for each song illegally hosted on the network.

LimeWire struck back with a countersuit against the RIAA alleging the RIAA engaged in "anti-competitive activities, illegal restraint of trade, tortious interference, and deceptive trade practices." After five years of litigation, the RIAA finally won out, with U.S. District Judge Kimba Wood ruling that LimeWire's users commit a "substantial amount of copyright infringement" and that the Lime Group "has not taken meaningful steps to mitigate infringement" (via Wired). This spelled an end to LimeWire as users knew it — although the platform ended up sticking around another five years while the Lime Group was tied up in litigation.

Settlement with the RIAA

In the fallout from the RIAA's successful lawsuit against LimeWire, the music industry giants asked for a payment of $75 trillion in damages, a conclusion likely reached based on the criteria of each song shared on LimeWire being worth an average of $150,000. Judge Wood said that a request for this amount of money "offends the canon that we should avoid endorsing statutory interpretations that would lead to absurd results" (via Computer World). Wood also mentioned the music industry could instead be entitled to a payment in the range of hundreds of millions of dollars to one billion dollars.

Of course, Mark Gorton and LimeWire ended up paying the RIAA nowhere close to $75 trillion, or even one billion dollars. Gorton's lawyers settled with the RIAA for $105 million, which is speculated to be less than his net worth. RIAA lawyers suggested during Gorton's damages hearing his net worth exceeded the $105 million figure, as he had $100 million tied up in a Roth IRA account alone before accounting for his yearly revenue as the head of Tower Research Capital LLC and the worth of his home.

Frostwire

The meteoric rise and unprecedented success of LimeWire, combined with the hole it left in the P2P file-sharing space spawned several clones over the years with FrostWire standing out as one of the most popular thanks to several key similarities. The program emerged concurrently during LimeWire's peak in 2005. Just like LimeWire, FrostWire initially operated on the Gnutella network, allowing users to search for files and download them directly from other connected users' computers. Additionally, FrostWire's mission mirrored LimeWire's in that it was easy to use and could support a wide array of file types.

Unlike LimeWire, FrostWire was not the brainchild of any one person. Rather, the idea for FrostWire evolved collectively as a response to LimeWire's decision to filter out content on the platform in order to better comply with the RIAA. In 2011, one year after LimeWire's shutdown, FrostWire transitioned out of the Gnutella network, becoming solely a BitTorrent client. The decision to leave the Gnutella network behind proved correct, as BitTorrent remains one of the most common protocols for sending and receiving files of all sizes.

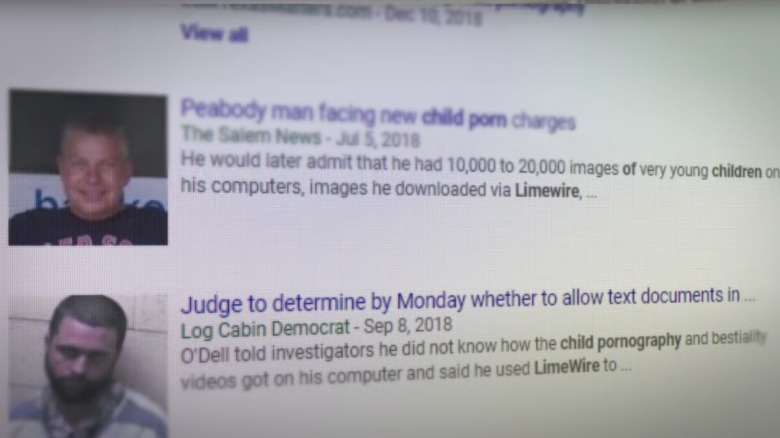

Prevalence of child pornography

The ugliest consequence of the lack of regulation on the Gnutella network meant that unsavory individuals had the ability to share some of the most heinous content imaginable. A 2003 study from the U.S. General Accounting Office found that its analysis of 1,286 titles and file names identified through KaZaA searches found that about 42 percent of the images had titles and file names associated with child pornographic images. LimeWire unintentionally helped facilitate this, although GAO's study shows that the malpractice extended far beyond LimeWire's scope.

The freedom LimeWire allowed meant sexual predators could not only look up forms of child pornography, but plant child erotica images in other files to offend and even implicate unsuspecting users. One such example of this happened when Matthew White, 22 at the time, discovered that some of the files he downloaded featured child pornography. He quickly deleted the files, but when FBI agents showed up at his home a year later, they recovered the deleted file. White accepted a plea deal for three-and-a-half years but still had to serve a decade of probation and register as a sex offender for the rest of his life.

If you or someone you know may be the victim of child abuse, please contact the Childhelp National Child Abuse Hotline at 1-800-4-A-Child (1-800-422-4453) or contact their live chat services.

Limewire shuts down

LimeWire's shutdown coincided with Judge Wood's ruling, and the software was officially shut down on October 26, 2010. The end of the platform came abruptly, and company morale at the time was still relatively high. In a corporate blog post posted a few months before the injunction, LimeWire CEO George Searle described his excitement for what the next 10 years will hold for the company by writing, "We're thrilled about our new service that will offer music fans an unmatchable digital music experience and new ways to discover content, without being restricted by device or location."

The shutdown had consequences that extended beyond its massive user base. Johnny Tan revealed LimeWire had to lay off one-third of the company during its lengthy litigation with the RIAA. "Lots of tears and feelings of betrayal on that day," Tan told Mel Magazine. "Before that, it was a tight-knit team. Everyone believed in what was possible, and no one left."

Global Production Manager Jarret Battisti expressed additional optimism to the publication over the creation of Grapevine, a streaming-esque service that predated Spotify, designed to move LimeWire more in line with the RIAA's demands. Regardless, LimeWire now has only its complicated yet powerful legacy to fall back on.

LimeWire today

LimeWire returned in 2022, but not as you knew it. The website and branding have been repackaged into an NFT marketplace. Non-fungible tokens (NFTs) are digital assets that can be bought, sold, and traded over the Internet with cryptocurrency. The idea behind owning one is closely related to why people buy art and other collectibles and decorations — buying it makes you the sole owner of a unique object or piece of data. What was once a company that encouraged P2P file-sharing at no additional cost is now what it describes as a "digital collectibles marketplace for art and entertainment."

Although there has been plenty of positive press surrounding the supposed revival of LimeWire, founder Mark Gorton has not endorsed the venture and has actually condemned the use of the LimeWire name. "I am not thrilled about an unrelated group of people using the LimeWire name," Gorton told TorrentFreak. "Using the LimeWire name in this way creates confusion and falsely uses that brand that we created for purposes for which it was never intended."

Since the original LimeWire trademarks have expired and the new LimeWire uses a reimagined logo, the new group was not under any legal obligation to disclose their plans to use the LimeWire name with Gorton. Time will tell how much longevity this new venture actually has, though it is also worth noting it has no affiliation with Mark Gorton and the original LimeWire.

Legacy

Like Napster, LimeWire left behind a complicated but important legacy in digital media. The service pioneered P2P file-sharing in mass quantities, and even though LimeWire is gone, P2P file-sharing continues to exist, albeit in different forms. The speed at which users could access digital media also opened the door for paid services in which consumers could pay a subscription and access different libraries of digital content in the form of streaming services. LimeWire's presence also forced the music industry to pivot more towards digital content and allowed artists to share their content in an alternative way.

However, LimeWire's legal struggles overshadow the sizable footprint it left on the music industry and the consumption of digital media. Years of litigation ultimately brought the company to its knees while highlighting the ethical complexities and tensions between copyright protection and digital sharing. Still, the fact that anyone could share anything on the platform (including inappropriate content and deadly computer viruses) did no favors to the company, leading to its ultimate dissolution.

Nevertheless, LimeWire legacy is primarily one of innovation, and its relaunch in 2022 is further proof that LimeWire's impact on the digital future may have been more positive than negative.

[Featured image by VQuiche via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | CC BY-SA 4.0]